If you sift through the list of all publicly listed French companies, you will inevitably stop when coming across this particular name.

"The Company for the Eiffel Tower" makes you wonder if it's possible to buy a stake in the wrought-iron lattice tower in Paris.

Can you?

The company is no longer what it seems. Better still, it provides a useful lesson for anyone looking to generate genuinely new, original investment ideas.

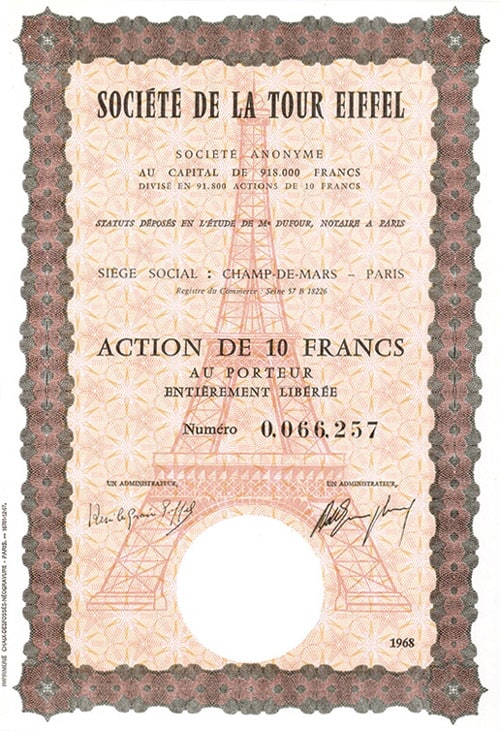

The 1889 Société de la Tour Eiffel stock certificate.

A gem of French economic history

The Société de la Tour Eiffel (ISIN FR0000036816, FR:EIFF) is, indeed, the company that Gustave Eiffel founded in 1889 to design and build the tower of the same name.

Today, the Eiffel Tower is the world's most visited monument that requires paying an entrance fee. Over 7m people pay homage to the unusual building every year. Since 1964, it has enjoyed the status of a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

When it was built, it was the tallest manmade structure in the world – a title that it held onto until the construction of the Chrysler Building in New York in 1930. It was the first building in the world to surpass the 200-metre and 300-metre mark in height. To this day, it has the European Union's highest observation deck open to the public.

Come to think of it, the Eiffel Tower wasn't all that popular initially, criticised by some of France's leading artists and intellectuals for its design. The self-proclaimed "Committee of Three Hundred" (one member for each metre of the tower's height) was formed by prominent figures from the arts who sent the petition "Artists against the Eiffel Tower" to the French government:

"We, writers, painters, sculptors, architects and passionate devotees of the hitherto untouched beauty of Paris, protest with all our strength, with all our indignation in the name of slighted French taste, against the erection … of this useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower … To bring our arguments home, imagine for a moment a giddy, ridiculous tower dominating Paris like a gigantic black smokestack, crushing under its barbaric bulk Notre Dame, the Tour Saint-Jacques, the Louvre, the Dome of les Invalides, the Arc de Triomphe, all of our humiliated monuments will disappear in this ghastly dream."

Gustave Eiffel went on to build the tower despite the opposition and after overcoming financial obstacles. Its original purpose was to give Paris an additional attraction to celebrate the Exposition Universelle of 1889. It was supposed to be in place for 20 years, and then be dismantled.

Little did even Gustave Eiffel know how popular his tower should prove with the public. Initially, the operating license was extended primarily because of the tower's great use in the growing field of radio telegraphy. It was also used for meteorological observations and – somewhat oddly – to perform experiments on the action of air resistance on falling bodies. Later, tourists started to visit in ever-growing numbers.

Until 1979, the Paris-listed Société de la Tour Eiffel was, indeed, a way for the public to buy a stake in the operation of the Eiffel Tower.

I first came across the company in the early 2000s, when I manually sifted through every publicly listed company on the Paris Stock Exchange (which, by the way, led to my now infamous story about Monaco's Société des Bains de Mer).

However, I quickly realised that the Société de la Tour Eiffel no longer had anything to do with the tower, except for its name.

And that's where a useful lesson lies for those among you who are looking to generate new, exciting investment ideas by themselves.

The valuable "brute force" approach to equity research

Running a filter through databases like Bloomberg is one way to generate new investment ideas. However, with anyone and everyone having access to public databases, will you be able to generate genuinely new investment ideas using sources that – literally – millions of other investors around the world are using?

One way for me to broaden my horizon of investment ideas is to manually sift through every single company that is publicly listed in a particular country. It's been a lifelong habit of mine that in each country I travel to, I pick up a local newspaper. More often than not, it will contain a list of all publicly listed companies – even today.

Manually looking at one company after another (from A to Z) isn't exactly an exciting task per se. However, it does make you look at potential investment cases that you would never have noticed otherwise.

Examples include:

- Companies that are named after one particular business sector but pursue their activities in an entirely different sector altogether.

- Companies that were named after a product, brand or sector that used to dominate their business but which have grown to have their focus elsewhere now.

- Companies that own valuable stakes in other companies but go to great lengths not to communicate that they own such an asset.

By methodologically going through a list, you approach the subject of idea generation without your preconceived ideas and limiting emotions. It forces you to look at every single company.

You end up looking at all the cases that a filter run across a computer database would never pick up. Never mind the fact that even the world's best databases about public companies often include manual errors, or are outdated.

In our day and age, the use of tech is glorified, and automation of any kind is seen as a plus. There's artificial intelligence, and the fact that the Internet nowadays is swamped with investment-related articles that were written by machines.

Relying on a manual approach combined with human instinct is not a form of investment research that a pension fund manager would be fond of. Box-ticking corporate bureaucrats will always be looking for replicable processes – which is why anyone who engages in manual work can nowadays (and possibly more than ever) find overlooked special situations that are worth digging into.

I did as much with the stock of the Société de la Tour Eiffel, and I did so at an interesting time in the company's history.

Brits to the rescue (twice)

Over the decades, the stock of the Société de la Tour Eiffel had turned into a favourite of small-time French investors.

The company produced reliable income, and despite maintenance costs it could afford to pay out a nice dividend every year. Each time it approached the end of its latest concession from the City of Paris, the dividend yield went up because of the uncertainty whether the company could continue much longer.

In the 1970s, it all started to change. In the early 1970s, the 1980 expiry date of the latest concession loomed large. Maintenance costs started to increase, and there was uncertainty whether the company had to invest into an expensive new elevator system. As a result, it had to skip its dividend for 1973. The stock nosedived, which paved the way for one undesirable investor to build an influential stake.

James Goldsmith was widely considered to be one of Europe's nastiest corporate raiders and vulture investors, and one who operated from London. Goldsmith swooped in and picked up 25% of the stock at rock-bottom prices. He figured there was value to be extracted from the Société de la Tour Eiffel, through providing the funding for a facilities upgrade and a negotiation of an extension to the concession.

The French financial and political establishment was in shock that the enfant terrible of capitalist Britain had taken control of its national icon. Goldsmith was a bon vivant who openly lived with two separate families in the UK and France, respectively (one wife, Annabel, provided the name for London's famous night club, Annabel's). Goldsmith was known for his ruthless methods in business.

A French bank, the Crédit Commercial de France, was roped in to buy out the raider. Goldsmith made a tidy profit, and the French establishment subsequently looked for ways to prevent such unpleasantness from ever arising again.

The Société de la Tour Eiffel was not granted an extension to its license. Instead, in 1980, the concession was granted to a new company, the aptly named Société nouvelle d'exploitation de la Tour Eiffel (New Company for Operating the Eiffel Tower). The French government nowadays operates the Eiffel Tower.

The Société de la Tour Eiffel became what is known as a listed shell. It no longer had an operating business, but the legal entity remained listed on the Paris Stock Exchange. The company was effectively dormant, outside of keeping some financial investments and taking care of its regulatory requirements, such as filing annual accounts.

When I sifted through the A-Z of listed French companies during the early 2000s, I ended up researching the company. As a listed shell, it fitted into a profile that I had already benefitted from many times during my investment career. Listed shells usually get picked up by an entrepreneur before too long, and are granted a new lease of life when someone injects fresh ideas into the company.

Indeed, in 2004, a duo of British real estate buffs took control of the situation. Mark Inch and Robert Waterland operated a private investment firm, which had the backing of no lesser investor than George Soros.

At the time, creating new real estate firms and listing them on a stock market was a quick way to generate wealth. The two Brits took control of the dormant Société de la Tour Eiffel and announced plans to build a EUR 1bn real estate portfolio in Paris and elsewhere in France, to inject new dynamism into the old company. The old company was the first to utilise new French legislation for creating publicly listed, tax-advantageous Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs, or Sociétés d'Investissement Immobilier Cotées (SIIC) in French).

It worked, at least for a while.

Before the plan had become public, you could have picked up stock in the old company for less than EUR 40. At the 2007 peak of listed real estate firms, the stock was trading for EUR 140.

As Les Echos reported in early 2007: "Société de la Tour Eiffel is in full renaissance". The appearance of this article also marked the peak of that cycle for real estate companies.

Source: Les Echos, 18 January 2007.

A research approach that you can learn from

Following some corporate ups and downs, the Société de la Tour Eiffel today manages a EUR 1.8bn real estate portfolio focussed largely on commercial real estate in Paris.

The stock never fully recovered from the Great Financial Crisis, though. Today, it's trading at its lowest share price since 2009. Remarkably, it's lower than before the British entrepreneurs gave the company a new lease of life. It was a success for investors during the initial hype of real estate stocks, but it has fallen out of favour ever since. Current macroeconomic worries about commercial real estate in Europe aren't exactly helping either.

Société de la Tour Eiffel.

Still, it's a beautiful example of the kind of company you can find in dark, overlooked corners of the stock market – if you are willing to make the effort!

Europe, in particular, still has a large number of such companies hiding in various corners of its fragmented, underdeveloped stock markets. It's a rich hunting ground, which some investors exploit on an ongoing basis.

With one such investor – who has enjoyed remarkable success in his career applying a brute force approach – I will soon be publishing an extensive interview.

In the meantime, there are worse things you could do than take the A-Z of listed companies in your home country, and start to go through them one by one. It's tedious, but it'll lead you to the most fascinating of finds.

Or, alternatively, leave this work to me. ![]()

An investment case that you might not have noticed otherwise

Swatch Group is one of those companies that were named after a product, brand or sector that used to dominate their business but which have grown to have their focus elsewhere now.

It's the perfect example of an overlooked special situation worth digging into that you only come across through some manual work.

The Swiss company should see its share price jump purely based on the expectation of possible change – the stock's record-low valuation could turn out a temporary bargain.

An investment case that you might not have noticed otherwise

Swatch Group is one of those companies that were named after a product, brand or sector that used to dominate their business but which have grown to have their focus elsewhere now.

It's the perfect example of an overlooked special situation worth digging into that you only come across through some manual work.

The Swiss company should see its share price jump purely based on the expectation of possible change – the stock's record-low valuation could turn out a temporary bargain.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post: