Images by Nataliya Hora / Shutterstock.com (bottom left), footageclips / Shutterstock.com (bottom right)

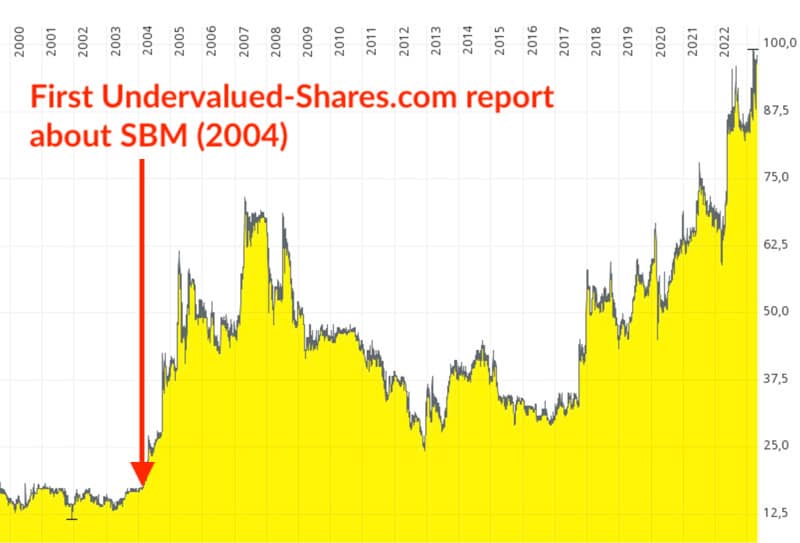

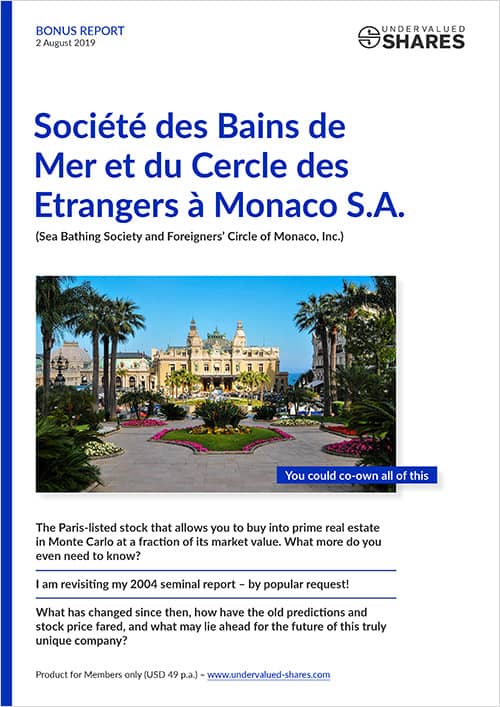

The stock that represents the best real estate in Monaco, SBM, has just reached a new record high. Why the investor interest? Property values in the tiny principality continue to go from strength to strength, and are now the highest in the world. Not bad for a place that until the 1850s had been a barren stretch of agricultural land presided over by a family of financially challenged aristocrats. The share price of SBM gets dragged along by the country's overall economic success.

The microstate (comprising just 208 hectares) is a world-famous example of how very small jurisdictions can grow faster, get richer, and be more successful overall than bigger countries. They often also score higher on aspects such as crime, unemployment, and public services.

Places like Singapore and Liechtenstein are other famous examples, but not the only ones.

Nowadays, the swathe of successful microstates that are dotted around the globe gets complemented by efforts to establish private cities with quasi-sovereign rights and even new countries. For some of these projects, fundraising among real estate investors and venture capitalists is carried out right now.

Is this going to form a new investment theme or asset class? How could this look like, and what might be its biggest attraction to investors?

Citrus orchards in downtown Monaco in the 1850s – do you recognise the iconic coastline?

Many fantasies – and some real-life opportunities

You can't speak about the entire concept of micro-jurisdictions and new countries without mentioning the legendary 1980s niche bestseller "How to Start Your Own Country" by Erwin S. Strauss.

After all, who has not at least once dreamt of starting their own country?

Strauss's book primarily dealt with ill-fated efforts and joke countries, like the tiny Principality of Sealand, which tried to establish itself on a deserted platform in the North Sea. Unsurprisingly, it never managed to get international recognition, but its promoter and self-styled Prince of Sealand, one Roy Bates, sold plenty of commemorative stamps and "passports" along the way.

Mention new countries, and (at least until recently) most would have put you down as a fantasist, conspiracy theorist, or outright fraud. The existing 195 countries in the world generally don't like it when someone tries to add new ones, which is why it's extraordinarily difficult to get a new country added to the list of widely recognised jurisdictions. The recent high-profile case of Liberland may be legally right to claim that a patch of land between Croatia and Serbia had genuinely been left unclaimed by either nation – "terra nullius", in legal terms. However, there is a difference between being right and winning your case. Unsurprisingly, the Liberlanders struggle to even visit their stretch of home country without staring down the barrel of a Serbian or Croatian soldier, let alone establish a residence there.

There is an entirely serious and relevant background to it all and increasingly, investors can make use of it, too.

Speedboats vs oil tankers

Small nations have long had a funny reputation. In the world of nationhood, bigger has long been seen as better. The tiny ones often became the butt of a joke, or were outright ignored.

Why, though? If big was great, why aren't school classes made up of 100 students?

Common sense and hard data dictate that smaller nations should receive more attention, especially in the current world environment.

Small nations are more governable, because there is less of a distance between the governing class and the subjects. More effectively governed countries tend to better withstand the hurricanes of history and prosper even in rapidly changing circumstances.

This was first extensively analysed in the 1985 book "Small States in World Markets: Industrial Policy in Europe" by Peter J. Katzenstein. His work showed that small states in Europe had succeeded due to their ability to "adjust to economic change through a carefully calibrated balance of economic flexibility and political stability". Even though Katzenstein's work focussed on Europe, most of the points he made were just as relevant to small states elsewhere in the world.

In the context that is relevant to investors, two of the most prominent examples would be those of Hong Kong and Macau:

- In the 1950s, Hong Kong was an impoverished backwater with no natural resources, no jobs, and no discernable USP for attracting investors. Its subsequent agility and outright boldness in introducing low-government policies – much owed to the efforts of British bureaucrat John James Cowperthwaite –turned it into one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, and made many with some economic stake fabulously wealthy simply by holding on for the ride.

A single man turned Hong Kong into what it is today – this is his history.

- Something similar happened in Macau, a remote, forgotten outpost of the long-defunct Portuguese empire only two decades ago. The introduction of gambling laws put the jurisdiction on fire, growing its economy an incredible 26% (!) in 2004 alone. In 2006, my post as director of a USD 300m residential property fund in Macau allowed me to witness first-hand how fast a small jurisdiction can transform itself. What larger nations sometimes can't accomplish in 20, 30 or even 50 years, a smaller jurisdiction sometimes pulls off in five or ten years.

Without a doubt, cases like Hong Kong and Macau have inspired a more recent investment proposition – which may actually just be an old one but reborn in a new guise.

The investment case for "Private Cities"

The concept of so-called Private Cities has made a lot of headlines over the past decades, and the last few years in particular.

Forbes describes this phenomenon as follows:

"Private cities, generally marketed as being 'better, cheaper and freer than existing state models', have become the new trend in the 21st century urban development. They are mixed-use developments where people live, work and play that are presided over by a CEO rather than a mayor – a company rather than a government.

In some ways, private cities are viewed as a 'win-win' type of shortcut, as governments can get their new developments built for them via private capital rather than tax dollars and still take a cut of the earnings, while private firms can profit at each stage of the urbanization process.

Private cities, kind of like special economic zones, often have their own sets of rules which often run perpendicular to the laws of the nations they are geographically located within. They are essentially legal wild cards – a swath of land purchased by a private company that can be run as that company sees fit. They are wild cards where the conventions of the broader country don't apply, where new labor regulations, tax codes, financial laws, business and property registration systems, and education models can be implemented and tested. The ideas behind many private cities tend to be very libertarian: get government out of the way and let the people prosper."

The world's leading authority on this subject is Dr. Titus Gebel, a German entrepreneur who, after selling his publicly listed company, moved his family to – you guessed it – Monaco. Dr. Gebel authored "Free Private Cities: Making Governments Compete For You", the single most useful the book about the sector, created the Free Cities Foundation as a think tank, and hosts the annual Liberty in Our Lifetime conference.

Yours truly with Dr. Titus Gebel in Monaco in January 2023 – picking the brain of a leading thinker.

Over the past decade or so, a number of free city projects have been promoted through several guises and legal frameworks. Prospera on the island of Roatán in Honduras probably represents the single most famous (or infamous) one.

Prospera is an autonomous zone with a private government and its own fiscal, regulatory and legal architecture, established under the groundbreaking Honduran "ZEDE" laws (Spanish: Zonas de Empleo y Desarrollo Económico; English: Zone for Employment and Economic Development). Depending on who you ask, Prospera's success gets a big thumbs up or a big thumbs down. I have never been and never had a horse in that race, but it does seem like the volatility of Honduran politics has not exactly done the project a favour. However, in terms of trying to achieve something ambitious and creating plenty of public awareness for a new subject along the way, Prospera deserves a lot of respect.

Quite a few cities in what is now the United States were seeded in a similar way. European royal powers granted the right to establish private, for-profit settlements, which led to the formation of New Amsterdam in 1626 (now: New York) and the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1628 (now: Boston), to name just two examples. These were high-risk, venture capital-style projects to get new settlements off the ground. They were the ZEDEs of their days, and land values in these locations have probably increased by a multiple too high to even grasp. However, don't ask about the difficulties of the initial period and the delays. Buying Manhattan for the equivalent of some trinkets and turning it into the world's richest city was a spectacular investment coup in terms of the underlying land value, but it will have experienced many bumps along the way.

With such cases in mind, should we take these ideas more serious?

Some of the world's most successful investors have done so already. Little-known investment fund Pronomos Capital, for instance, set out to help create and then back investment cases of this nature. The fund used to publish highly informative articles on its blog (currently offline for a revamp), but little is known about the performance of its investments. Early investors said to have been involved as backers include Marc Andreessen, Peter Thiel, Tim Ferriss, and Naval Ravikant – famous names in the world of finance and venture capital.

You'd be surprised how many investable assets exist in this space.

A surprisingly diverse sector

The sector of investments that closely relate to sovereign rights of one kind of another has diverse and diffuse boundaries, which is a feature and an opportunity but also an obstacle.

Prospera, for instance, is variably described as a free private city, a Special Economic Zone, and even a relatively conventional real estate project. It's difficult to put these different projects into clearly delineated baskets.

The history of all this goes back way further than most people think, and it even extends to famous household names that few would ever associate with the subject.

E.g., Disney World in Florida is also a private city of sorts. After Walt Disney secretly bought up lots of land in what was a largely useless area of Florida, he petitioned lawmakers in the state for special powers to govern the area around what is now the amusement park. As a result, Disney World enjoys a special tax district, akin almost to being its own state. Only recently did this entire subject make it back into the public debate, after The Walt Disney Company (ISIN US2546871060, NYSE:DIS) got into a public spat with Florida's governor, Ron DeSantis.

The same holds true for Monaco's Société des Bains de Mer (ISIN MC0000031187, PA:SBM). It is a for-profit, publicly listed company but majority-controlled by the country's ruling family and – unsurprisingly – regularly the beneficiary of favourable government decisions, such as the repeated extension of its casino monopoly. While the old saying "SBM is Monaco, and Monaco is SBM" isn't factually true (SBM owns a mere 5% of the principality's landmass – the government's ownership of 4,500 apartments for subsidised rentals to long-standing citizens is actually a bigger portfolio, it's directionally accurate and makes a pretty good point. Buy into the company, then ride on the coat-tails of the country's overall success and its diverse community of residents from 139 nations.

Where do you draw the line between these cases, and what should be part of such an asset class and investment theme?

Sovereign rights of some kind have to be in the mix, for sure. With that in mind, there is an entire selection of different options and variations.

For stock market investors, the single most relevant and accessible category are probably those of Special Economic Zones. Based on the definition by the World Bank, SEZs are "demarcated geographic areas contained within a country's national boundaries where the rules of business are different from those that prevail in the national territory." Through SEZs, governments create exceptions to their own rules – select havens from the status quo that prevails elsewhere in the national territory.

Since 1995 alone, the number of SEZs in the world has grown from 500 to 5,400 across 147 countries. These figures are based on an analysis by Thibault Serlet, whose research and advisory firm Adrianople Group created the largest dataset on SEZs. Serlet's LinkedIn feed is a treasure trove of valuable information, where I learned that the EU has banned SEZs because it wants to decrease competition. Who knew? Who is in the least bit surprised?

SEZs enjoy a little-known, but actually fairly widespread presence on the world's stock markets. There are dozens – and potentially, hundreds – of publicly listed real estate firms that own property in SEZs and similarly privileged zones:

- The aptly named Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone Limited (ISIN INE742F01042, IN:APSE) is a USD 15bn behemoth that operates Mundra, the first port-based SEZ in India.

- Canadian pension fund Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec made headlines by placing a USD 2.5bn bet on DP World, a Dubai-based company that also owns the Jebel Ali Free Zone. Previously listed on the stock market, DP World went private in 2020 because it felt public market investors didn't appreciate its unique angle and long-term approach.

- When Cambodia started to emerge from decades of economic isolation, it floated the Phnom Penh Special Economic Zone (KH1000050000, CSX:PPSP) as one of the first five companies listed on its nascent stock market.

Examples such as these make it clear why there is growing overall interest in this sector and the underlying trends.

MUST-watch: a 15-minute tour de force through the world of SEZs by Thibault Serlet at the Liberty in Our Lifetime conference 2021.

Forgotten subjects returning to the fore

Old trends and topics usually come back before too long.

One of my all-time favourite books that no one has ever heard of is Harry D. Schultz's "On Re-Making the World – Cut Nations Down to Size", published in 1991. As "Uncle Harry", author of the legendary but sadly now-defunct HSL Letter, argues, the world "should debate and develop the concept of mini-states". His book is very much of the same vain as Katzenstein's earlier work, but more practical in its approach. Schultz makes concrete arguments in favour of breaking down many of the world's best-known nations, including doubling the number of countries in the world to at least 500 before too long.

Schultz's work was long disregarded as the flight of fancy of an eccentric author who (funnily enough) was based in Monaco. However, its core theme is actually gaining traction of late, and the book may yet experience a renaissance.

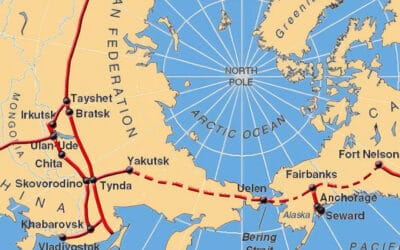

We may not have seen many nations broken down into smaller bits (yet), but there is a clearly visible trend that could be seen as a precursor, with direct relevance for investors: deglobalisation, regionalism, tiny-ism or whatever else you might want to call it.

Where else would this be more prominently the case right now than Florida? The third largest state of the union by population numbers has recently gone its own way and thus become an incredible economic success story. It's now even shaping the national conversation, as a monumental feature in the Financial Times recently recognised. By not following a federal health mandate and making its own, local decisions, Florida did a world of good both for itself and the idea that jurisdictions have to be in competition with each other.

The US breaking down into smaller bits has become quite a subject of recent debate, at least in some corners of the public conversation. Whether by secession or civil war, a significant percentage of the US population now expects the union to disintegrate. Sceptics will reasonably argue that this sentiment had always been prevalent. In the meantime, it's difficult to deny that these developments aren't leading to concrete, attractive investment cases. The St. Joe Company (ISIN US7901481009, NYSE:JOE), for example, holds massive land reserves in Florida's Panhandle region that are suddenly becoming much more attractive. It's about as clear-cut a case of a beneficiary of US regionalism as they come.

You don't have to see nations break into parts to benefit from this trend. All it takes is a fine antenna for the Zeitgeist to bring opportunity through change. The overall opportunity may be driven not just by what's actively being decided in small jurisdictions, but also by the negative changes in larger jurisdictions.

Big Country residents pay notice

Much as it's obvious that smaller jurisdictions tend to be more agile, it's equally obvious that most Western democracies are pretty stuck nowadays.

Following 50 years of government expansion in the everyday lives of its citizens, the Western world has some of the highest ever governmental share of GDP, taxes, regulatory burden, and indebtedness. This usually comes combined with low birth rates, uncontrolled immigration attracted by welfare systems, and an entrenched political caste that seems incapable of enacting serious change. Right now, these countries are learning the difficulty of balancing higher inflation, higher interest costs on unprecedented levels of debt, and the explosive pace at which off balance sheet obligations from entitlement programmes are coming due.

Since the events that unfolded from 2020, I have given up on these countries to pull themselves out of their quagmire – a sentiment that is perfectly summarised by Dr. Gebel's must-read seminal article "Parallel Structures Are the Only Way to Freedom" (also available in German). Dr. Gebel argues that large Western democracies are basically unreformable and therefore, anyone who does not enjoy their system should work towards establishing alternative bases, such as free, private cities. I expect that this article will one day be a cornerstone piece in history books that try to explain where it all went wrong.

It all comes with important conclusions for investors, too.

If Western democracies are stuck in a slow-burning forever crisis, will they offer attractive returns over the decade(s) to come? How does their return profile look like once you make a fair adjustment for the seemingly increasing political risk?

Someone who recently had this difficult and inconvenient conversation, and created quite a stir, is venture capitalist Balaji S. Srinivasan. His book "The Network State" discusses how to build the successor to a nation state, a concept Srinivasan calls the network state. Srinivasan believes that technology will allow to build an intentional community that initially consists just on the Internet, but later crowdfunds the purchase of land and eventually grows to a level where it achieves diplomatic recognition. A pipedream and another joke country scheme to separate the naïve from their money? Srinivasan, who likes to create a bit of controversy and debate, has achieved quite an impressive level of engagement on this subject, straddling a million followers on Twitter. He will have studied relevant books such as "The 10 Rules of Successful Nations" by Ruchir Sharma, which barely a Western politician will have even heard of. Srinivasan's theme of wanting to go from a one-person start-up society to a million-person network state is worth following.

Who knows, maybe one day a firm like Binance will acquire El Salvador and rename it El Binanco? Okay, just kidding… Although there is a half-serious YouTube video that asks how much it costs to acquire a country, and another one that wonders if Amazon could purchase the nation of Cyprus.

There is no doubt about it, this entire subject, complex and diffuse as it may be, is increasingly garnering attention. It's also a fair bit of fun!

And it all leads straight back to the investment alternatives offered by the sector of microstates, free cities and new countries. It's a subject where everyone can now pick from a variety of alternative investments.

I myself take this entire subject so seriously that I have just put myself out there with a daring but exciting investment proposition.

My own microstate investment project

I have such a strong personal view of the supremacy of smaller states that I based myself in one. Since 2017, the only place in the world that I call home is Sark, the tiny self-governing jurisdiction in the English Channel. Even though it has just ≈500 residents, it's got a full-blown parliament and is entirely in charge of its taxation, budget, and governance.

Sark in the English Channel.

In 2020, a lack of new residents prompted me to launch a campaign for bringing new residents to the island. It went viral across the media, and helped boost the local economy and real estate prices. I used to joke at the time that I had turned Sark into the world's fastest growing economy, which may have actually been true.

My latest project, which enlists the support of my licensed fund management company Sarnia Asset Management, involves an offer to purchase Sark real estate worth up to GBP 100m, and help create a 50-year master plan for the island. An initial assessment of what such a master plan could look like will be carried out by The Prince's Foundation, an organisation created by King Charles III which is visiting Sark on 24 April 2023.

Source: Bailiwick Express, 19 April 2023.

Sark has the potential to become a showcase micro-jurisdiction, with a wonderful community and some extraordinary metrics in areas such as resilience and genuine (!) sustainability. As the team that represents the King's values said in a BBC Radio interview, other island jurisdictions throughout the British Commonwealth could learn from such a model case. If my suspicion is right, it could also be a compelling case for investors to get involved, and may even become a place where (even) more of my readers want to move to.

You'll probably read more about these efforts across the media soon, and it's an investment case that I have a personal passion for.

However, it's also just one case among many. There is tough competition between small jurisdictions that want to attract investment, and only the best will manage to attract the kind of smart capital that such nations and jurisdictions will vie for.

Obvious and less obvious opportunities

In over three decades, I have never seen such a diverse set of investment propositions in this space than currently.

For venture capitalists, there are early-stage opportunities managed by the likes of Pronomos Capital and Dr. Gebel's Singapore-based firm, Tipolis (which is currently in negotiations with several governments and planning a financing round by mid-year). That's before you drill into the plethora of free cities propositions that has sprung up around the planet, and which include Prospera but also ideas such as turning an island in Vanuatu into an SEZ for Bitcoiners. I have seen one such case offer a 200-2,000x return (with risk commensurate to the potential payoff, of course).

One of the more conventional possibilities includes buying real estate in locations that are potentially going to benefit from a general, broader shift to smaller jurisdictions. SBM and Monaco are the more obvious opportunity.

There are also derivative opportunities, which take a bit of lateral thinking to uncover:

- Many investors and savers are desperate to find financial institutions that offer true safekeeping of assets without the risk of being affected by the eventual political, financial and social fallout of large Western welfare states. I already wrote about The Bank of N. T. Butterfield & Son Limited (ISIN BMG0772R2087, NYSE:NTB), a USD 1.5bn market cap private bank based out of Bermuda with no branch exposure to the US or the EU. (Disclosure: Investment entities that I represent are in a business relationship with Butterfield Group.)

- Successful creators of free cities will probably need a new form of tech, e.g. to run a kind of sought-after decentralised government. As Cointelegraph put it, "successful smart cities will be impossible without decentralized techs" and "blockchain technology promises to be the foundational network layer for many systems underpinning successful smart cities." Why bother with real estate if you can invest into creating the underlying software and technology of free cities?

- One overlooked aspect of all these developments is that of Governance as a Service (GaaS), as opposed to governance as bullcrappery. If new jurisdictions succeeded, there'd have to be private enterprise service providers that provide effective governance services. Appropriate companies could make a mint out of this.

Just as much, you could discard the investment aspects of today's article and take it all down to a personal level. Why not have your investment benefit from a lower tax rate? There are many small jurisdictions that allow you to do so. Besides saving taxes, these jurisdictions can protect you against the vagaries and follies of Clown World governments, provide you with more freedom, have you live in a lovely community of like-minded individuals, and generally increase your happiness. As an example, I pay GBP 5,000 in annual taxes in Sark and don't even need to declare income or assets, besides having full control over how I arrange affairs such as healthcare of pensions.

Am I the only investor interested in this?

What puzzles me is, why is there no ETF yet that tracks the GDP growth rates of the world's ten most successful micro-jurisdictions? These nations are so obviously economically superior in many ways (or at least, different), that it'd seem a slam dunk to offer exposure for private and institutional investors.

Why isn't the economic performance of major Western nations benchmarked against the performance of smaller nations?

There are many more questions to be asked and opportunities to be explored. No investment exists in a vacuum, and anyone investing money should take an interest in some of the potentially far-reaching transformations in today's world.

In any case, there are probably more surprise outcomes hiding among these questions than are apparent at first sight.

With folks like Srinivasan chewing on this subject, I keep an open mind as to where the journey goes.

Your feedback counts

Today's article has been a thought experiment.

I'd love to hear from you:

- Which investment-related aspects am I missing?

- Where are particular opportunities that you feel are worth investigating?

- What aspects of this theme are particularly compelling to you?

Should I feature opportunities arising in this sector in more detail and more often (and if so, in which format?)?

Would you like to visit Sark, or learn more about the opportunity that I am working on?

A hassle-free long-term investment

It's never a bad idea to buy real estate in locations that are potentially going to benefit from a shift to smaller jurisdictions.

Société des Bains de Mer, the company that owns the best real estate in Monaco, is an obvious opportunity.

Its stock has just reached a record high.

Buy into the company, then benefit from the share price dragged along by the country's overall economic success.

A hassle-free long-term investment

It's never a bad idea to buy real estate in locations that are potentially going to benefit from a shift to smaller jurisdictions.

Société des Bains de Mer, the company that owns the best real estate in Monaco, is an obvious opportunity.

Its stock has just reached a record high.

Buy into the company, then benefit from the share price dragged along by the country's overall economic success.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post: