Many countries feature companies that are not listed on a stock market, but whose stocks you can buy and sell nonetheless. The underlying shares trade on unofficial, privately organised exchanges – or even at auctions!

Historically, these unlisted companies offered some of the best-ever investment opportunities. Provided, of course, you knew how to find them.

Today's Weekly Dispatch will explain this sector to you and give you a few examples of why the market for unlisted stocks is one to pay attention to. I'll show you some cases of investors striking it rich by investing in these unusual companies, and tell you the prime reason why there are still opportunities waiting to be discovered.

What are "unlisted" stocks?

To make sense of the term, you first need to know what a "national registered exchange" is. In the US, it is an organised market that is registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), i.e., a stock market that is recognised and regulated by the federal government. Nasdaq and the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) are two such markets. Such an exchange will make sure that for all the securities it provides a market for, the underlying companies adhere to SEC regulation.

Any company that decides to list its share on such an exchange will have to comply not just with corporate law, but also with SEC regulation. E.g., corporate law obliges every company to keep accounts and to furnish its shareholders with a copy upon request. SEC regulation goes a step further by requiring that the annual accounts are made available to the general public and the media, too.

The same concept comes under different names in individual countries. E.g., the UK speaks of "recognised stock exchanges". Different term, same thing.

Where there are registered exchanges, there will also be unregistered exchanges. In the US, you can operate a market for trading securities without recognising SEC regulation.

A good way to think about these differences is to apply the old term of a "grey market" or "black market". The stocks of companies that are not listed on a nationally registered exchange can be traded by anyone who dares to step their toes into this market, but the marketplace for these stocks will be a dog-eat-dog kind of market. As an investor, you'll be out there by yourself. The SEC will not look after you.

My readers already learned about one unlisted company

You may remember my article about the Californian farming company that has "secret" water rights that are potentially worth billions.

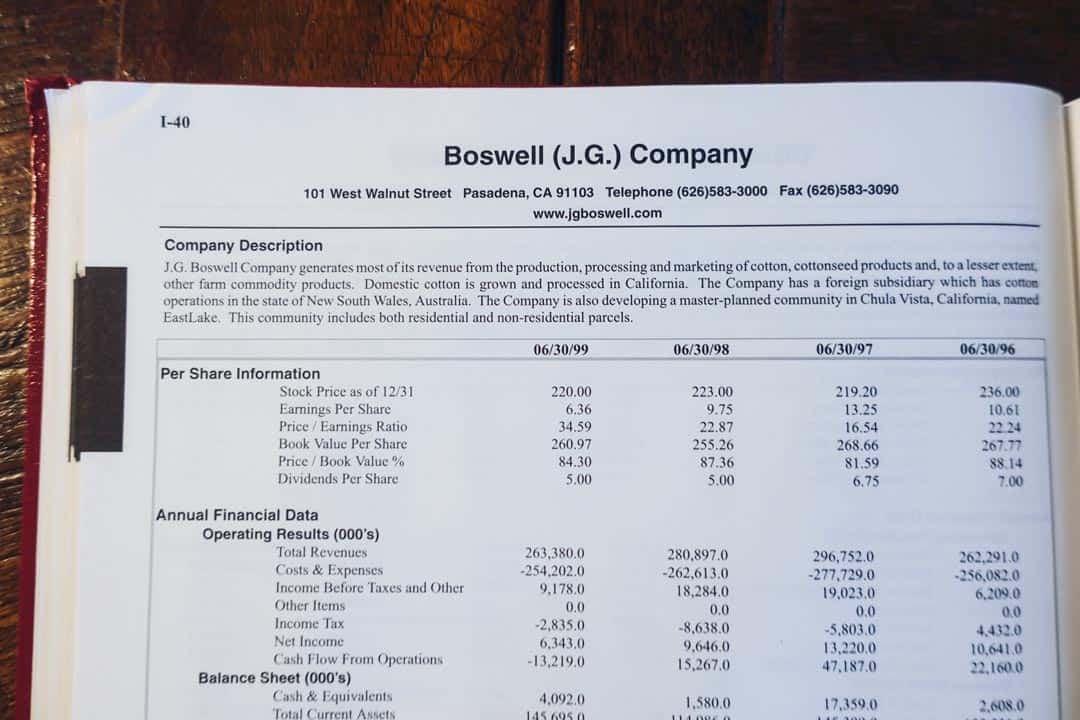

J.G. Boswell is a great example to show that there is no clearly delineated definition of what exactly constitutes "unlisted" stocks.

E.g., from a regulatory perspective, the company is unlisted, because it does not fall under SEC regulation. However, there are market makers for the stock and a daily price. If you have a US brokerage account, you can easily buy and sell the stock. The process is not much different to buying any officially listed stock, because it only involves a call to a US broker. The differences lie mostly in your rights as shareholder and a few practicalities involved with ownership.

J.G. Boswell steadfastly refuses to put any information about its business in the public domain – and it doesn't have to either, because it's not under SEC regulation. As a shareholder, you can get a copy of the accounts, which is your right under corporate law. However, the company threatens to block shareholders from receiving future annual accounts if they are found to leak information on the Internet or to the media. Such bullying has no basis in corporate law, but try taking them to court over it. You'll be up against a local judge whose wife is likely to play tennis with the wife of the company's CEO. Good luck with blowing your money on that! Something like this would never happen to you if you simply bought into listed companies that are trading on the New York Stock Exchange or Nasdaq.

Think of it as share trading in a Wild West style. It's you, your horse, and your gun. You are out there by yourself, looking for gold.

How can you trade such unlisted stocks, and why would you even want to?

As you will have gathered by now, these markets for unlisted stocks lack transparency. For investors, a lack of transparency can be the best-ever gift. If other investors are in the dark, you can take advantage of them.

Provided, of course, you know how to play the game.

Buffett's early successes with opaque markets

There are a handful of publicly known stories of how Warren Buffett made some of his first money.

E.g., in 1950 he picked up stocks of the National American Fire Insurance for a price of USD 27. The company earned USD 29 per share, i.e., it had a price/earnings ratio of less than 1. From today's perspective, it's almost incredible that such a situation ever existed (even p/e's of 3 or 4 invoke disbelief because they're simply too low). The numbers were right, and this opportunity did exist. It was due to a lack of transparency.

I wasn't able to find out which exact market Buffett acquired the stock on, but it's clear that he managed to exploit a situation that nowadays you could only ever find among unlisted companies.

As Buffett described it: "This company was located right here in Omaha, right around the corner from where I was working as a broker. (But) none of the brokers knew about it."

The fewer people follow a particular company, the more likely it is that the market is mispricing the stock. Less publicly available information, less media exposure, and fewer informed shareholders is the combination you are looking for. Under these circumstances, you might be able to gain an edge through diligent research and pick up undervalued investments at outrageously advantageous prices.

E.g., the Californian farming company could one day make bucketloads of money for its shareholders by simply selling its water rights. We know that now, but information about it has been kept from the public domain for decades. The stock was largely priced based on the value of the farming operation, rather than the money-making potential of the century-old, legally-guaranteed water rights.

Until the early 2000s, no one had ever taken a close look at these water rights. The stock was trading around USD 200, driven mostly by the company's performance in growing almonds and tomatoes. With the onset of the Internet, information about California's peculiar water rights legislation started to become available, and it subsequently spread among investors. The stock went up to USD 1,100 in a matter of four years. Once the secret is out, illiquid markets can make for a steep rise. Supply dries up, and the price shoots up.

How did Buffett (and others) find such opportunities?

Buffett: "No one will tell you about these businesses. You have to find them. … You have to turn over a lot of rocks to find those little anomalies. You have to find the companies that are off the map - way off the map."

Among the many tools that he used were also some printed compendia of unlisted companies. There are books and other resources that can help you locate these opportunities.

Books and online registers can be your best friend

In 2005, Buffett reportedly got himself a copy of the "Korean Stock Market Guide". An article on the Internet described his subsequent research:

"Buffett spent 5-6 hours leafing through the pages ... Daehan Flour sold 25% of the flour in South Korea, which had a large and stable economy. It’s earnings over the last few years: KRW 12,870 (Korean Won), KRW 18,000, and KRW 22,830. … The stock price was 38,000 won. "You have to make money buying stocks like this at 2 times earnings. Brokers aren’t going to tell you about Daehan Flour.""

Having done quite a bit of research of this kind throughout my career, I also love compendia of companies – in those rare cases where you can get them!

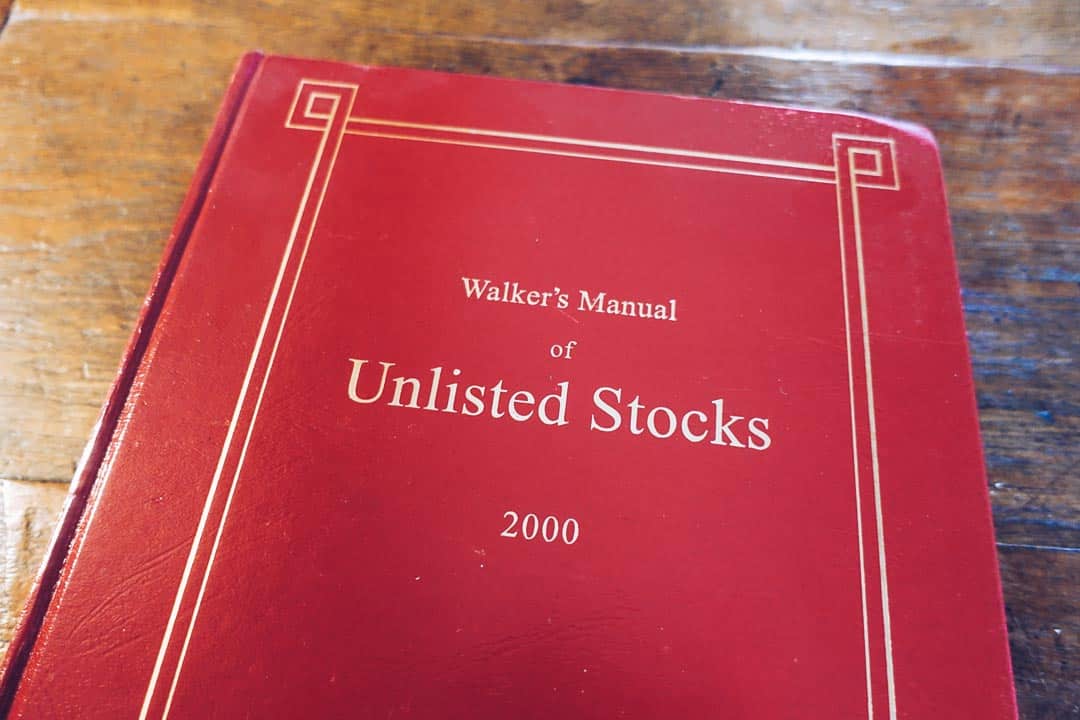

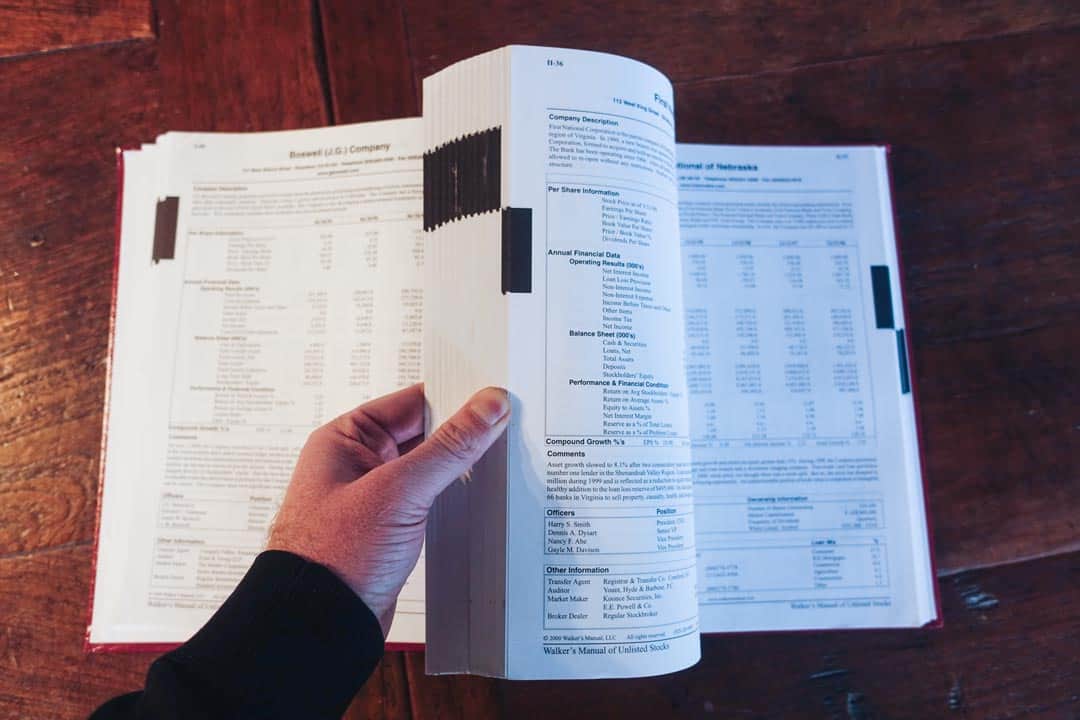

A rare, out-of-print book from my collection illustrates how broad the market for unlisted stocks is.

The "Walker's Guide to Unlisted Stocks" was a regularly updated printed compendium. It provided an in-depth profile of every known US company that was not listed on a recognised exchange but whose shares still traded freely. On 700 pages (weighing nearly four pounds!), you found about 500 such companies whose stock you could trade if you knew how and where.

Rare, but occasionally available from out-of-print book vendors.

A treasure trove of difficult-to-find information.

Sadly, the Walker's Guide last appeared in 2003, and it has since become a collector's item worth a few hundred dollars.

Still, it serves its purpose for digging out unusual opportunities.

E.g., J.G. Boswell, the Californian farming company, was listed in the guide. If you knew where to look, you could have gotten a first glance at the accounts without actually being a shareholder. That's how you beat the market, and how you outmanoeuvre uncooperative company officials.

I recently stumbled across an American investor who in 2016 had sifted through all the companies in the 1996 issue of the Walker's Guide. He found that of the 500 or so companies contained in the guide, about 130 were still around. Many of them continued to trade on different "grey" markets. An article he published about his quest lists out what these different markets are. American readers might find it interesting to see how many different variations of "unlisted" there are.

As Buffett once put it: "Value still exists today if you look hard enough."

"Secret" company information, contained in a publicly available (but little-known) book.

The world is your oyster – usually, for a limited time only

Such markets for unlisted companies exist around the world, and no one seems to have a list of them. The fact that no one even keeps a register of all markets for unlisted stock around the world is brilliant. Remember, a lack of transparency is your friend!

However, you have to overcome hurdles other than just trading these stocks.

E.g., these markets sometimes appear for a while and then vanish. You will need to look at the right place at the right time. If you are too late, you miss the opportunity.

Here is an anecdote from my life as speculator and truffle hound looking for unlisted gems.

During the 1990s, I bought stock in several unlisted German housing associations. These were a peculiar kind of entity because they operated as a Public Listed Company (PLC, or AG/Aktiengesellschaft in German) but with a special tax status similar to that of a quasi-charitable operation. You could become a shareholder in these entities by buying stock, but your rights as a shareholder were heavily restricted both by law and management. It was neither a for-profit company nor a charity.

Some of the quirkier aspects of investing in these entities involved:

- The stock often consisted of bearer certificates, i.e., you had to deal with physical stock certificates. Buying and selling involved sending stock certificates by registered mail, or meeting up and exchanging wads of cash. Bearer certificates are virtually the equivalent of cash, so you ended up having to entrust thousands (or tens of thousands) worth of stock certificates to the postal system.

- In the case of some of these companies, you only became an actual shareholder if the management agreed to register your name on the list of shareholders. I remember one particular company where management refused to register you if you weren't also a registered resident of the city where it owned residential housing. You could purchase the bearer certificate and be the legal owner of the certificate, but you couldn't get your name on the register and, therefore, were refused rights such as entry to the annual shareholder meeting. Such a practice clearly had no legal basis, but try taking company officials to court in a town where they are one of the largest players in the local economy and generally viewed as the good guys.

- As a quid pro quo for operating more as a charitable housing association than a for-profit company, these entities received tax-free status from the national government. All of their profits were tax-free, which helped them accumulate massive amounts of assets over the decades.

In the early 1990s, one Buffett-style German investor launched a takeover bid for one of these entities. The stock price multiplied, and the bid succeeded, which resulted in other investors (such as my young self) getting interested in the entire sector of unlisted housing associations.

These were pre-Internet days. On some occasions, I travelled to a city to visit the local company register. Unlisted companies were obliged to file a copy of their accounts with the local company register, and these were open to visits by members of the public. You had to inspect the documents in a reading room, which in some of the smaller registers involved sharing the office desk of the person in charge of the register. For a fee, you could request a photocopy of these documents, which were then mailed to you a few weeks later. At times, I asked for copies of hundreds of pages. Several dismayed, work-shy bureaucrats refused to provide them, until I threatened to inform their supervisors. Corporate law does provide a useful stick. In the market of unlisted securities, you need to defend yourself.

The stock of these housing associations had often been placed with tenants, who were the ultimate uninformed investors. In some instances, it was possible to buy a stake in these entities at 5% or 10% of the underlying asset value. The current owners simply had no idea what potential treasure they owned, or they had inherited them and didn't know the background of these companies. Receiving any offer at all for an otherwise illiquid investment turned them into abiding sellers.

Image: Glen Berlin / Shutterstock.com

German housing projects made fortunes for cunning investors.

Eventually, legislation for these housing entities changed, which propelled the entire sector to the fore and led to stock prices soaring. Subsequently, many of these entities got privatised and sold off to private equity investors. Fortunes were made as a result.

Surprisingly, such opportunities tend to arise in ever-new parts of the world.

Each time you think that you've seen it all and the well has run dry, there is a new opportunity popping up somewhere else.

Countries where capitalism is only just starting (even today)

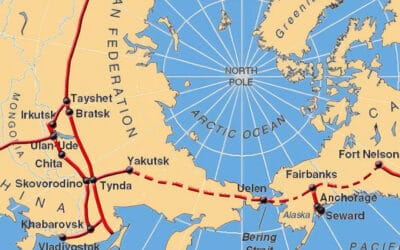

If you were around during the early 1990s, you might remember the "privatisation vouchers" that were issued in Russia and various Eastern European countries.

After the Berlin Wall fell and the Soviet Union collapsed, these countries tried to turn their state-owned enterprises into privately-owned, for-profit companies. To turn citizens into capitalists, the respective governments issued privatisation vouchers.

Everyone received a certain number of these vouchers, which could then be exchanged for stock in any company that they wanted to become a stockholder in. The vouchers were physical documents, and most citizens of these countries had no experience in dealing with such a matter. It was the ultimate Wild West situation with millions of uninformed sellers and entire economies up for grabs.

There are numerous cases of cunning Western investors flying to Russia and elsewhere, bringing suitcases of dollars with them. By buying up vouchers on the opaque market, they managed to secure themselves stakes in some of the best companies of these countries for the proverbial song.

Here is how one such investor, Jim Mellon, described his dealings in vouchers in an interview with the Financial Times:

"In 1994, we discovered Russia, which was my first really big break. I had read somewhere that Russia was privatising its industry and that they were handing out certificates that represented a share of the post-Soviet state to every adult. These state enterprises covered everything from local hairdressers to the big oil and gas companies.

You were given a bit of paper and it was tradeable, and foreigners could buy them. You would then use these bits of paper at auctions for each individual company.

…

We had USD 2m of our own capital to spend. I hired two bodyguards and went down to the vegetable market (of Vladivostock) where old ladies were trading these coupons en masse for roughly USD 25 each. We bought a big bag of coupons, and handed about 80,000 to a broker who put them into the auctions, held by the central government. At the time, the average Russian did not think they were worth more than a bottle of vodka. After four or five weeks, I got a fax, saying the USD 2m was worth USD 17m and what should we do. I said sell! That was the really big break. "

These Russian vouchers for privatised stocks multiplied in value.

"That was then", you'll probably say.

However, similar opportunities do still arise. Or at least, that's my gut feeling in the case of one particular country.

I was tempted to go to similar lengths after my visit to the stock market in Uzbekistan. Tashkent has an "official stock market", though, in reality, it currently operates more like a hotchpotch of unlisted stocks that change hands under adventurous circumstances and in tiny numbers. It is very early days for the stock market of the former dictatorship, and it has little similarity with the organised, transparent stock market that we are used to.

What I saw during my visit made me believe that there must be 1950s Buffett-style value investing opportunities hiding among the 200 Uzbek companies. When a local broker told me of one company trading at 10% of book value, I knew that this was something worth taking a closer look at.

I wrote about it in my early-2019 series about Uzbekistan, and I may yet go back to dig a bit deeper.

Even the safest country of all offers such opportunities

It wasn't just in risky Russia or exotic Uzbekistan where such opportunities arose, but also in safe Switzerland – and they continue to be available there until today!

In Switzerland, unlisted companies have long been a large and fairly visible feature of the economy. There are hundreds, if not even more than a thousand, unlisted companies in Switzerland that have outside stockholders but are not listed on a recognised exchange.

The country's split into different regions, languages and local cultures had probably played a significant part in this market arising in the first place. For as long as I can remember, there have always been countless Swiss companies that were not listed per se, but whose stock was known to change hands through a variety of means.

- Sometimes, the company itself decided to bring buyers and sellers together. You could ring up the company and enquire about prices for buying and selling; or, nowadays, register your interest through their website.

- There were always a handful of financial services companies that made a market in these stocks, in exchange for a fee.

- In other cases, you had to resort to bidding for stocks at auctions of bearer certificates.

The market is incredibly quirky. Some of these companies refuse to accept foreigners as shareholders, or even other Swiss people from outside of the valley. Others don't pay a dividend and instead hand out free chocolate bars and cable car tickets. I am not making this up!

Free chocolate bars aside, there is a serious investment angle. Just as in the case of Buffett's early investments, there have always been unlisted Swiss companies with enormous hidden reserves on their balance sheet. As and when these reserves are finally mobilised for the benefit of shareholders, the stock price can multiply.

In the day and age of the Internet, researching these Swiss opportunities has become a lot easier. E.g., there is now a portal website that reports about 300 of these unlisted Swiss companies. If your German is good enough, you can research many of these companies from the comfort of your home.

Because of the increase in transparency that has already taken place, valuations are already a lot higher than they were in the 1990s or early 2000s. However, I bet you a cookie (or a Swiss chocolate bar) that there is still value to be found among some of these Swiss companies.

Maybe, one day, I'll write a feature about one or two of them. An extensive trip to Switzerland is long overdue.

Many of Switzerland's mountaintop facilities and cable cars are owned by unlisted companies that you can buy into.

Watch this space for more

I take my hat off to anyone who makes an effort to research unlisted opportunities. They are hard work but can be all the more rewarding. There is even a small subset of investors out there who have made such opportunities the heart of their investment strategy.

I have no doubt that there are plenty of other such opportunities out there, in all parts of the world.

E.g., I have long kept an eye on one particular country that virtually no one would ever take a closer look at with regards to unlisted companies, but where several fascinating cases have popped up once I started scratching the surface. (And no, I am not referring to the unlisted South Korean company with assets in North Korea.)

Come to think of it, you may yet learn about some of them on my website.

Readers, please help!

As always, I am also using my site to learn from others. The knowledge residing among my ever-growing network of readers is one of the reasons why I am operating this site.

Which opportunities might my readers know of?

I'd be keen to hear about:

- Countries where markets for unlisted securities exist.

- Books and other guides about such markets.

- Particularly exotic and "extreme" cases that are worth looking into.

If you have any ideas in this regard, do drop me a note!

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post:

Get ahead of the crowd with my investment ideas!

Become a Member (just $49 a year!) and unlock:

- 10 extensive research reports per year

- Archive with all past research reports

- Updates on previous research reports

- 2 special publications per year