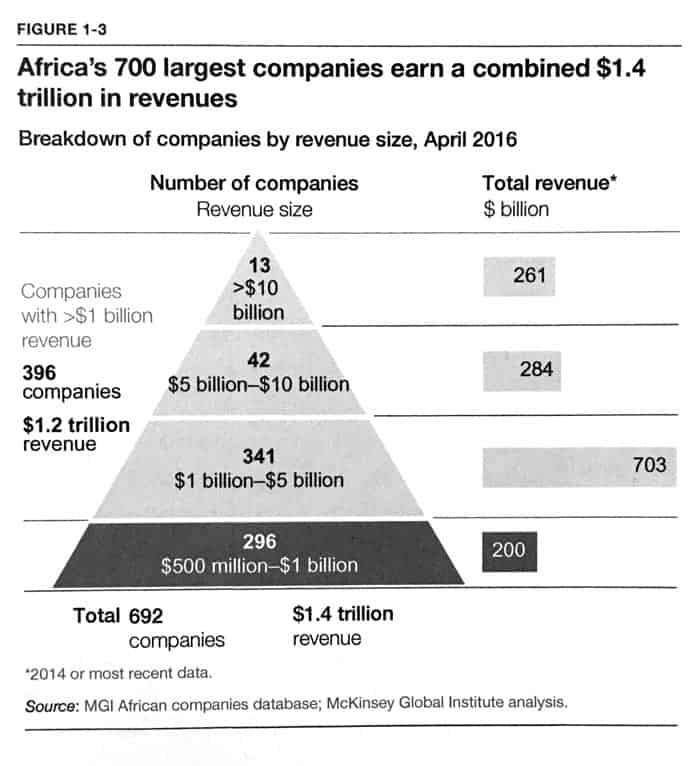

How many companies in Africa generate annual revenue of USD 1bn or more?

A 2018 survey asked 1,000 business executives to take a guess. Few said more than 50. Some even thought it was zero.

Wrong. There are 400 (!) such companies!

If you lower the annual revenue threshold to USD 500m, the number of companies increases to 700.

Notably, they are also more profitable and faster-growing than their global peers. Plus, many of them are listed on a stock market, either in Africa or internationally.

There are many other exciting but little-known facts about the Dark Continent, which investors with an interest in long-term growth stories should pay attention to. Today's Weekly Dispatch gives you a deliberately optimistic selection of these facts and figures – because you are unlikely to have read about them anywhere else. As ever, I'd like to provide you with a different perspective and food for thought.

Just for the avoidance of doubt, I am far from suggesting that Africa is a continent without problems. The challenges of doing business there are tremendous. However, the economies of sub-Saharan Africa have grown at an annual rate of 5% since 2000. That's a heck of a growth rate over a long period. Fortunes were made on the back of that, mostly by local entrepreneurs and investors.

Outside of all the challenges and risks, there is a lot to be said in favour of investing in Africa.

Many of the statistics in this article are sourced from this book, which is featured at the end of the article. For all other sources, I link through to the source material.

Demographics are destiny

We all know about Africa's mind-boggling population size. The continent's long-standing population growth, which stems from a birth rate of 4.7 children per woman compared to just 1.6 per woman in Western Europe, is one of the few subjects the media reliably picks up.

The continent's population currently stands at 1.33bn people. At the turn of the millennium, this figure was 791m.

The annual population growth rate has been hovering around 2.5%, albeit with a tendency towards slowing down.

Even with the growth rate slowing somewhat, Africa will have nearly 1.7bn inhabitants by 2030.

Let these figures sink in for a moment. Over the current decade, Africa will add almost as many people as the US currently has inhabitants.

Add to it the fact that the population is very young. Over 60% of the continent's people are younger than 25. To put this into perspective, Africa has almost as many young people as Western Europe and the US have in combined total population.

Some experts refer to these statistics as the "demographic reordering of the world". That term is both a scary and an exciting prospect, depending on how well prepared you are for it. Make no mistake, it'll happen in our lifetime.

The most predictable (but far from only) result of these demographic changes will be a change in demand for basic goods and services.

Young people will want to have access to Western consumer goods, buy a mobile phone, and get a bank account. Once they have risen further up to middle-class standard, they will want to buy a washing machine, get a mortgage to build a home, and take their family on holiday.

It's the same story that has played out in economies the world over since the end of the Second World War. It may seem a stretch to apply this kind of thinking to Africa, but most people thought the same about China back in the 1990s.

Such unmet, growing demand is where the investment opportunity lies.

It's noteworthy how lucky we are that we can now focus on these growth opportunities in Africa. That's because most of the political challenges from the continent's darker period have already been dealt with.

It's worth taking a quick look back at the more challenging times, though, just to get an overall perspective.

Until the 1990s, Africa had suffered from post-colonial growing pains

Africa has had a remarkable change of fortune.

Anyone older than 40 today will remember the continent as a former hotbed of military dictatorships, coups, and civil wars.

Indeed, things didn't start well after decolonisation.

One of the decisive moments for Africa during the 20th century – and now largely forgotten – was the "Winds of Change" speeches given by the Conservative British Prime Minister, Harold McMillan.

In 1960, he told the parliament of South Africa: "The wind of change is blowing through this continent. Whether we like it or not, this growth of national consciousness is a political fact."

It was a repetition of the same speech he had given in Ghana, another British colony, a few weeks before. It gained more media attention in South Africa, though, not the least because it also condemned the country's apartheid policy.

McMillan had merely recognised the inevitable. During the Second World War, many British colonies in Africa had stepped up to help Britain. They expected a reward in return, mostly in the form of economic opportunity and greater political autonomy. At the time McMillan toured the continent, violent resistance against the colonial masters had already broken out in Belgian Congo as well as French Algeria. His government was keen to prevent it from spilling over into British possessions.

The British government brought the timetable for granting independence to its African colonies forward by a decade. Following McMillan's speech, what is nowadays Tanzania was released into self-governance in 1961. Many other countries followed, including those of other colonial powers. The 1960s became Africa's period of decolonisation.

Sadly, the following 30 years up to the 1990s were not a great era for the continent. It's easy to design a flag and have a European royal family member hand over the keys to the governor's mansion. It takes much more time to put in place a functioning governance system. Governments need institutions, and institutions need to be built.

There was insufficient preparation for independence, and we all know the outcome. By 1970, no less than 18 dictators ruled on the African continent - many of them for decades to come, and some causing millions of deaths. The Cold War, where some African countries ended up as squares on the board of global chess games, didn't exactly help either.

It was only after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 that things started to turn around for Africa. The most visible case was, of course, that of South Africa. In 1990, the country's apartheid government released Nelson Mandela from prison and lifted the ban on his party, the African National Congress (ANC). Following a referendum in 1992, all South Africans were granted the right to vote in 1994. The changes that took place in South Africa catalysed changes elsewhere on the continent.

Without those changes, the opportunities we are looking at today probably wouldn't exist.

Here are some numbers to help you get our head around what has happened since.

A fast-growing consumer market – and unoccupied niches for entrepreneurs

Long-term figures about Africa are notoriously hard to come by and difficult to interpret:

- Many countries did not have reliable statistics until recently (and may not even have them today).

- There are different definitions of what constitutes "Africa". For example, some prefer to view Northern Africa as a separate entity. For this article, I am mostly referring to "sub-Saharan Africa", which refers to Africa without the countries that are bordering the Mediterranean (but even this term still has several meanings).

- South Africa distorts any statistic about the continent, because of its sheer economic might.

One useful way of looking at all this is to work out how many new consumers with disposable income the continent has created. That's an area where long-term, relatively reliable figures exist.

In 1990, 54% of Africa's population lived in poverty. By 2015, that figure had shrunk to 41%.

During the same period, the overall population of Africa has grown from 630m to 1.18bn.

Using these baseline figures, you can work out that between 1990 and 2015, the number of Africans not living in poverty has risen from 290m to 698m.

That's 408m *additional* consumers, or about the size of the EU's population.

In total, Africa in 2015 had 698m inhabitants above the poverty line. Being above the poverty line does not make you middle class. However, the Brookings Institution, an American research organisation, recently estimated that as per 2020, around 700m Africans have some disposable income. Ergo, you can view the number of Africans who are above the poverty line as your potential addressable market for goods and services.

Besides the sheer size of the market, let's look at some of the factors that make doing business (and investing) in Africa both daunting and exciting.

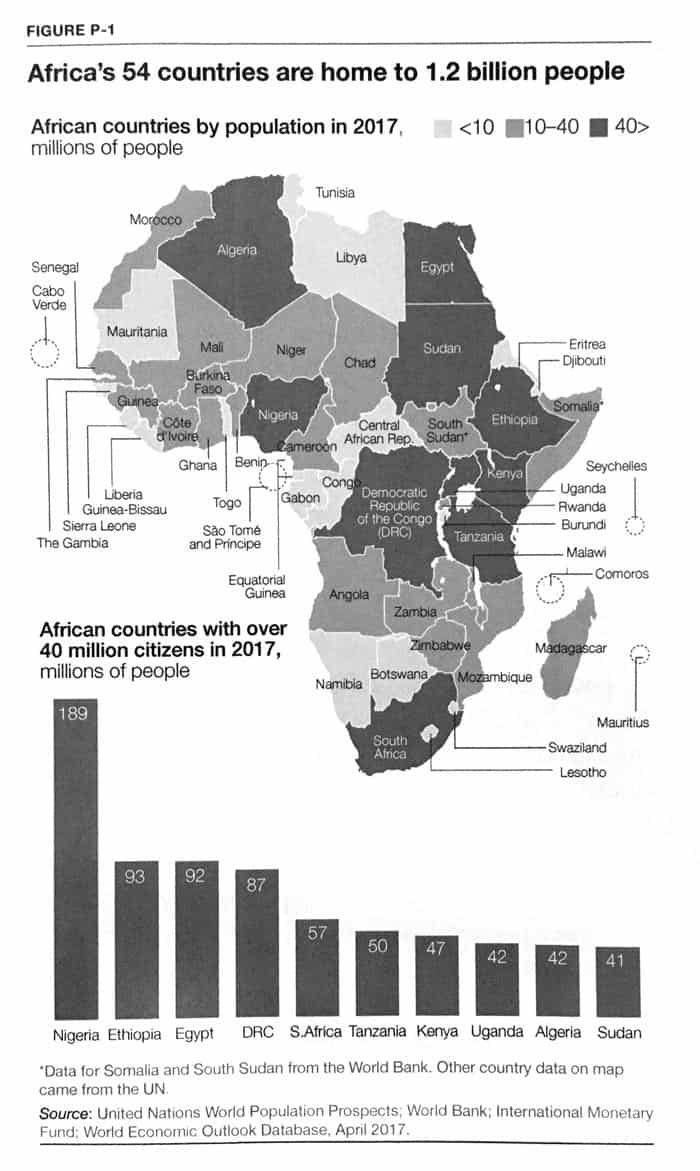

A decent number of African countries have a sufficient population size to offer economies of scale (source: Africa's Business Revolution).

Tremendous problems remain – but (technological) help is at hand

There is no denying that Africa is way behind the rest of the world, in almost all aspects.

Here are just some examples that fit in our context:

- Africa's 400 companies with >USD1bn in annual revenue are more than most people would expect. However, the figure is also a sign of Africa's weakness. Relative to other regions of the world, Africa only has 60% the number of large companies that it should have given its current state of development. The figure looks even worse once you consider that half of the continent's big firms are located in South Africa, aka the springboard for multinational companies. You could take a romantic view and celebrate the fact that the backbone of Africa's economy is small, family-owned enterprises. However, these don't have economies of scale, nor access to growth capital. Not having a sufficient number of large firms does leave consumers worse off.

Many of these companies have liquid stock trading somewhere on a global stock market (source: Africa's Business Revolution).

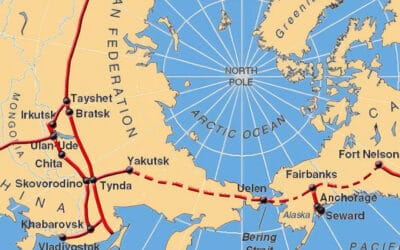

- In part one of this series, I mentioned how travelling from one African country to another often still involves flying to Europe and back. Overall economic connectivity among the continent's countries is poor, and the lack of trade staggering: inter-African trade makes up 14% of the continent's overall trade, compared to 68% in Europe.

- Retail options for consumers are also extraordinarily underdeveloped: every formal retail outlet in Africa caters for 60,000 people, compared to 400 people in the US. Two-thirds of the continent's retailing happens through informal retail outlets. Online shopping stands at a minuscule 0.5% of the African retail market, compared to 10% in the US and 17% in China.

The continent is still far behind, which is exactly what piqued my interest. Entrepreneurship is another word for solving problems. By tackling some of these problems, entrepreneurs can create fast-growing companies – and fortunes for the investors backing them. Africa is an enormous growth opportunity waiting to be used.

Just look at smartphone penetration as an example. The East African Community covers six countries with 170m people. Only 33% of this regional trade bloc's inhabitants have a smartphone. By 2025, that figure is projected to double. It'll then still be lower than the smartphone penetration in Europe and the US, which is nearer to 80%.

For anyone providing products and services to such fast-growing markets, there is a double-opportunity:

- Grow faster than many other markets (sub-Saharan Africa grows at roughly three times the speed as the G7).

- Reap much higher profit margins than your peers elsewhere in the world, because there is less competition in Africa.

Remember what I wrote about Nigeria's Dangote Cement in the first part of this series. The company has the highest profit margin of any dominant cement producer in the world. Say about Africa what you will, but if you can make something happen in Africa, your profit will be enormous.

Within this entire opportunity, technology deserves special mention.

Smartphones and other technology are changing the continent

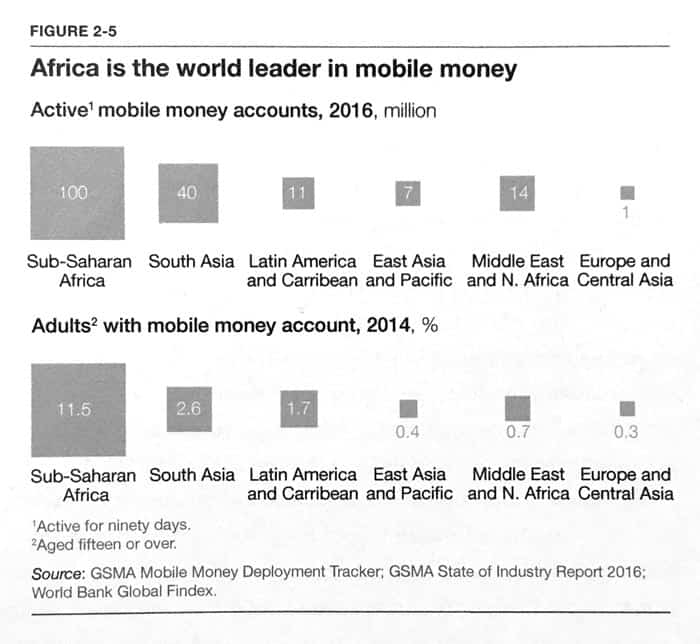

When I went on my 2007 roundtrip of African countries, mobile phones (not smartphones) had just started an economic and societal revolution.

Up to that point, hundreds of millions of Africans couldn't access basic services because they didn't have a mechanism to pay for them. Few had a bank account, and utility providers didn't want to run the risk of having to collect cash from customers living in informal shantytowns.

Mobile phones provided the solution because they allowed to transfer deposits from one phone to another. Suddenly, African households could pay electricity bills via their mobiles. Mobile telephony turned into a quasi-banking network, if only for small payments. It enabled commerce that otherwise would have been impossible. And it didn't stop there.

Payments via mobile phone have become vital to Africa's economies (source: Africa's Business Revolution).

Armed with mobile phones, fishermen could figure out which town to deliver their catch to while still at sea. It helped them get the best price, minimise excessive catch going to waste and avoid unnecessary journeys.

The famously unreliable African transport network became easier to navigate because information about delays and cancellations was shared via SMS, saving people hours of wasted time.

Affordable technology continues to make a huge difference in Africa. The potential for improvement is probably much bigger than elsewhere in the world because it starts from such a low level. Combine dramatically decreasing costs for technology with a tremendous accumulated backlog of problems, and you've got the recipe for rapid economic improvement.

There is a long list of areas where technology could come in to solve problems and meet unmet demand:

- So-called "agritech" could bring down the cost of putting Africa's vast unused arable land to use and maximise the agriculture industry's productivity (note that of the world's unused arable land, a stunning 60% (!) is located in Africa). Imagine a drone flying over African farmland to take infrared pictures, which will then alert the farmer to diseases well before they become visible to the naked eye. It will allow the farmer to treat his crop before any damage is done.

- Digital services as simple as a cross-city pooled taxi network (similar to "Uber Share") could help improve transport in places like Lagos, Nigeria. Here, transport is too bad to get anywhere, and the lack of connectivity reduces economies of scale for everyone (the average resident can only access 800,000 of the city's 21m people).

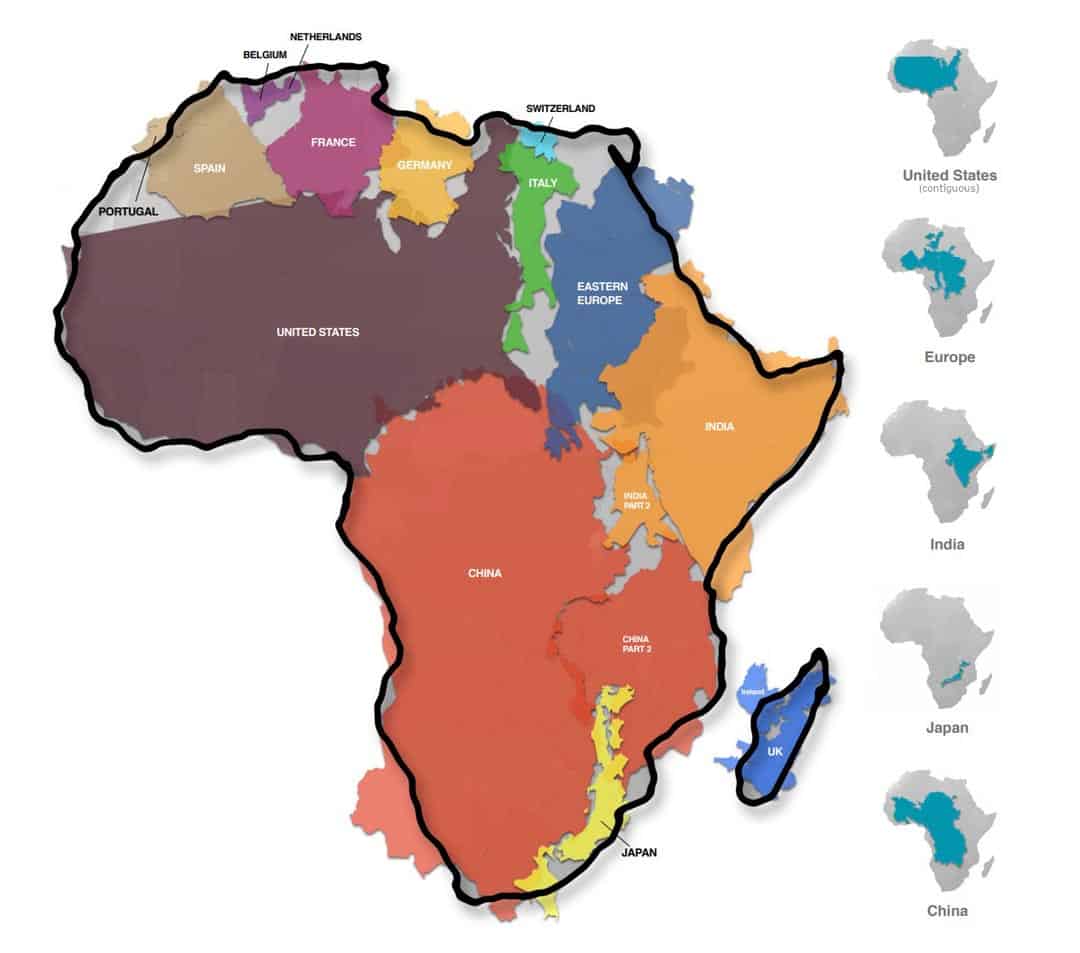

Hard to believe: the true size of Africa (source: Visual Capitalist).

These are mere examples, and there will be 1,001 others. There will also be heaps of problems that no one else had thought of until today (just like no one had thought of Uber or Airbnb before the companies were set up). Some of them will make a fortune for entrepreneurs and investors who are providing the capital.

The lower the base from which you start, the higher the percentage improvements once you get things underway. It's the base effect. For investors, getting in on the proverbial ground-floor opportunities could recreate some of the investment opportunities that the West has experienced since the beginning of the dotcom boom.

For entrepreneurs, the bigger a problem, the higher the potential reward.

Can we find Africa's hidden growth companies?

When you mention Africa to investors, they mostly roll their eyes and remember their misfortunes in investing in resource companies.

For a long time, Africa was best known for its countless exploration companies - gold, copper, uranium, oil, gas, and diamonds (besides others). Africa has probably only discovered 20% of its overall resources, leaving trillions (!) worth of commodities awaiting discovery. The lure of striking a gold vein – quite literally – has driven generations of investors to punt with African commodities stocks.

It's not like early-stage resource plays didn't occasionally make someone wealthy. Check back to my September 2019 Weekly Dispatch about UraMin, the company that rapidly minted billions for investors who had anticipated its success in locating uranium deposits.

Still, resource plays tend to be highly volatile and extremely risky. If a hoped-for oil well comes up dry or if a round of drilling for diamonds yields only rubble, you can kiss your money goodbye. That's what happens in 90% of all cases. Well, probably closer to 99%.

How, then, can ordinary investors benefit from Africa's promising long-term opportunities in growth industries?

What are the stocks that give you a chance to "relive" some of the gains that growth stocks produced for investors in the US, Europe and Asia during the 2000s and 2010s?

Might there be one or the other investment that covers a broad range of them, and allows you to simply sit on one growth candidate for the rest of the decade?

I am still investigating the question, but I may be narrowing in on a few possible candidates.

Later this week, I will be back with part three of this series.

That much is for sure: right now, most investors are massively underestimating Africa's potential for growth investment opportunities. I'll be working hard to uncover at least one suitable opportunity for Undervalued-Shares.com Members.

Book recommendation: I couldn't have written this Weekly Dispatch without "Africa's Business Revolution – How to succeed in the next big growth market" by Acha Leke, Mutsa Chironga and Georges Desvaux. Most of the statistics referenced in this article came straight from the book. If you'd like to learn more about the topic, this is the #1 book I recommend you purchase! It stood out among the half dozen books that I've read ahead of writing this series.

Blog series: Investing in Africa

There's more to "Investing in Africa" than this Weekly Dispatch. Check out my other articles of this three-part blog series.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post:

How can YOU tap into Africa's growth investment opportunities?

Most investors are massively underestimating Africa's potential for growth investment opportunities. Don't be among them.

Some truly exciting ground-floor opportunities await. I'll be disclosing one of them shortly, in a new research report for Undervalued-Shares.com Members.

Sign up now to unlock it!

Discover my favourite African growth investment candidates - for just USD 49.

That's the price of my Annual Membership, which will also give you:

- 10 extensive research reports per year

- Archive with all past research reports

- Updates on previous research reports

- 2 special publications per year

You won't find better value for money anywhere else...