Each decade produces an investment thesis that delivers outstanding results.

These theses usually start in a niche and initially attract scepticism, before snowballing into multi-trillion sectors that capture the public's imagination. They also tend to come with an acronym or a catchphrase – which help them spread and stick in peoples' minds.

In 2000, few investors cared about emerging markets. By the end of that same decade, investing in emerging and frontier countries was en vogue and had produced spectacular returns for early investors. "BRICs" was the acronym of the decade. It called for investors to put money into Brazil, Russia, India, and China.

In 2010, investing in online companies was still in its infancy, and most investors thought the leading Internet companies were fully valued. Today, the "FAANG" stocks are an acronym that no one even needs to spell out anymore. Their value has grown so fast that they are now a multi-trillion asset class of their own. The theme has spawned various lucrative subcategories, such as the "FAANG-BATS", which includes the Chinese online firms Baidu (ISIN US0567521085), Alibaba (ISIN US01609W1027), and Tencent (ISIN KYG875721634).

Had you caught any of these themes early on, you probably could have made enough money in a single decade to retire comfortably after that.

Which begs the question…

What will be the new kid on the block that captures the public's imagination?

Digital Decolonisation - "DigDec" - is a hot candidate.

Have you never heard of it before?

That's the point.

The DigDec theme could become one of the significant trends of the 2020s, and you can be part of it from a relatively early stage.

This three-part series will explain everything you need to know about DigDec and its investment opportunities.

The globalisation of online companies is no longer a given

A short six years ago, it looked like the American Internet giants were going to dominate their industries globally.

In 2015, TechCrunch looked into "Google's Quest To Bring The Internet To The Next Billion People".

That same year, The Guardian wrote about "Facebook satellite to beam internet to remote regions in Africa".

The following year, Newsweek described "How Jeff Bezos Is Hurtling Toward World Domination".

Much as these three firms remain very successful on a global scale, a more mixed image has since emerged. It's no longer plain sailing for the American tech giants' quest to expand around the world.

Look no further than the recent tussle between the Australian government and Facebook. As The Guardian just wrote: "Australia's move to tame Facebook and Google is just the start of a global battle".

A lawsuit in Europe could have similar stark effects on Facebook. A September 2020 headline read: "Facebook says it may quit Europe over ban on sharing data with US".

This theme extends across the range of American tech giants. Even Amazon had to realise that it cannot dominate all markets. As readers of my Weekly Dispatches know, highly success Amazon equivalents have sprung up in many regions and countries around the world, such as MercadoLibre (ISIN US58733R1023) in South America, Ozon Holdings (ISIN US69269L1044) in Russia, and Allegro (ISIN LU2237380790) in Poland. Never mind Alibaba as the national e-commerce champion in China.

The wealth generation caused by these firms is extraordinary. MercadoLibre is now worth more than the next three largest South American companies combined, Allegro more than the next three largest Polish companies taken together.

Half a decade ago, it looked like the digital world was going to revolve around six zip codes in California and Washington State.

From here onwards, the outlook is quite different.

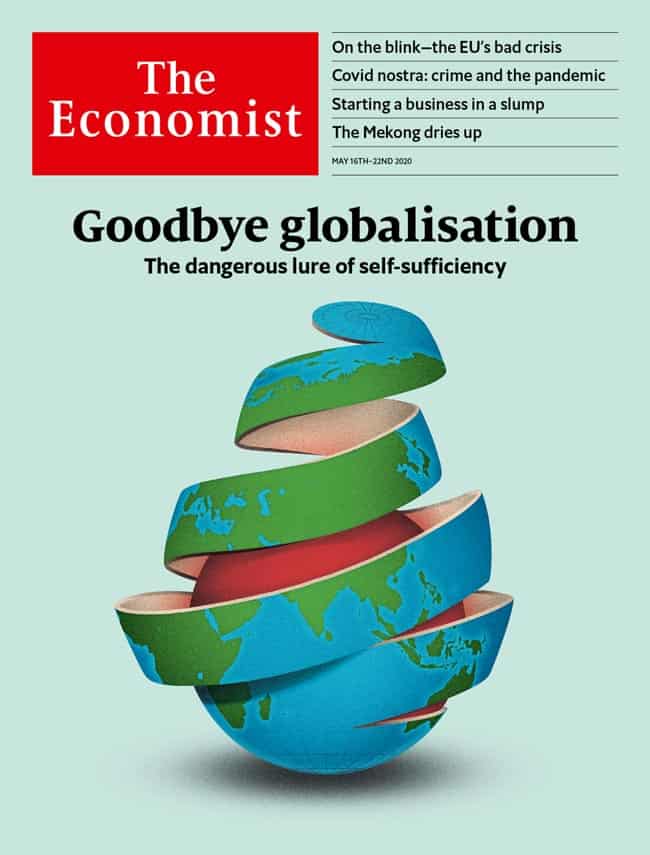

The trend towards ever-larger global online firms was dealt a lasting blow at the ballot box in 2016. Both the UK's Brexit referendum and the US presidential election signalled a massive shift in the public's attitude to globalisation, and they continue to reverberate around the world. It remains to be seen whether it's truly time to say "Goodbye globalisation", as the Economist famously stated on its 16 May 2020 cover page. However, we are indeed witnessing a growing trend towards localism, protectionism, and economic nationalism, all of which favour the emergence of a new breed of homegrown tech companies around the world.

Politics plays into this in ways that few have taken a closer look at yet. Recent developments in Asia provide a useful example.

In November 2020, 15 Asian countries representing 2bn people and 30% of the world economy signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). The trade agreement followed on the heels of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which the Trump administration rendered a lot less relevant when it pulled out in January 2017. The RCEP was negotiated without the usual lobbying interests of Silicon Valley at the table. As a result, the RECP gives its member nations much more leeway when it comes to providing (or blocking) digital access to its markets. It allows countries to exercise a vague "national security" provision to crack down on foreign technology businesses, should that be deemed in the national interest.

The kind of economic nationalism enabled by RCEP is a mere example, and it can be observed elsewhere. It even happens in Old Economy sectors, as illustrated recently by France's blocked takeover of supermarket chain Carrefour (ISIN FR0000120172) by a Canadian competitor over fears of food security. Protecting domestic companies will increasingly come to the fore in supply chain management and anything relating to perceived or real national security. This development is fuelled further by the experiences of the past 12 months involving a shortage of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and nation-states fighting over scarce vaccine deliveries.

Add the fact that no other industry creates highly profitable, valuable companies as fast as the technology industry. There is a lot of bounty to argue over.

The political aspects of this trend may sound negative, but it also happens against a positive backdrop. The world economy has matured, and there is less dependence on American (or European) players to provide solutions.

A new breed of "emerging market" entrepreneurs

What used to be "emerging markets" are now countries that feature a local class of entrepreneurs and professionals. Many of them were trained abroad or benefitted from accessing education online. They have access to global capital markets and venture capital sources that used to be difficult (if not impossible) to tap into if you weren't based in San Francisco, New York, or London.

Also, many markets around the world require in-depth local know-how to succeed, which the existing tech giants aren't always able to come up with.

A prime example is that of Gojek, the Indonesian ride-hailing service and "super app". The company was set up in 2009 by two Indonesians with degrees from Brown University and Harvard Business School. Their ride-hailing service started with 20 motorbike taxis (Indonesian: "ojek") and one tiny call centre. Four years later, the company managed to get venture capital from international firms. By 2020, it had become an Asian "decacorn", i.e. a unicorn worth ten billion dollars. Its app-based services now cover payments, food delivery and other essential services. Gojek provides work for an incredible 4m (!) people.

Uber, anyone?

In a telling development, the American firm that you would expect to be Gojek's competitor, left Indonesia in 2018.

Uber didn't stand a chance against Gojek (Image: Dedi Cahyono Putro / Shutterstock.com).

The emergence of such local and regional tech champions spawns entire new sectors, including in indirect ways. Naturally, the American firms are not taking any of this laying down and often try to acquire a presence in a new market. However, the resulting acquisitions indirectly provide further fuel for this trend. In 2017, Amazon spent USD 580m on taking control of Souq, the Arabic-language e-commerce platform. By doing so, Amazon handed huge cheques to local entrepreneurs and investors. Some of them have gone on to fund the next generation of Arabic start-ups. Global companies buying out these national and regional players only adds further fuel to the local tech ecosystem. The genie is out of the bottle.

Increasingly, emerging markets are taking charge of their digital destiny, rather than to rely on foreign companies helping them prosper in the digital age.

As I finished up this article, the Financial Times reported "Twitter feels heat as India tightens grip on social platforms". In a mixture of local regulations and domestic entrepreneurship, the country has been "promoting indigenous Twitter rivals such as Koo, a fledgling microblogging app that operates in eight Indian languages and has been downloaded 3.3m times".

At a time when tech giants are increasingly accused of acting like nation-states and introducing globally applicable quasi-legislation through their terms of use, entire countries are trying to break free from the (mostly) American diktat and, instead, pursue their own course.

Hence the term "Digital Decolonisation".

It's not entirely dissimilar to the decolonisation movements of the 1950s and 1960s.

Would Gandhi use Twitter or Koo? And why does it matter for investors?

When entrepreneurs and managers build indigenous solutions for domestic challenges, their financial backers can make fortunes.

Sometimes, these new firms will even benefit from the national protection they are granted. With diminished international competition, profit margins could be higher than those of its peers elsewhere.

Clearly, as investors, we should take an interest in this.

Emerging market tech firms will gain in relative size and influence

Only 8% of the world's population are Americans, yet American tech giants make up eight of the world's ten largest tech companies. The combined market cap of the ten largest American tech companies makes that of tech companies in the rest of the world pale in comparison. If you throw China into the mix, you have two countries dominating the tech sector globally when measured by the market cap of publicly-traded tech companies.

But will it stay like that?

Just for the avoidance of doubt, I do believe the FAANGs and other American (or Chinese) online companies are great businesses that will continue to thrive. However, they are not going to conquer all parts of the world, as once believed.

In terms of relative size and influence, they are probably already past their zenith.

Consider the following:

- 90% of the world's population that is younger than 30 years live in developing countries.

- Internet connectivity in developing countries is catching up fast. If you have any doubts, check my May 2020 research report on Helios Towers (ISIN GB00BJVQC708), the mobile phone tower company that brings mobile bandwidth to Africa. My report's figures about Africa's development will surprise you!

- Everything is politicised these days, and that includes the question of how and where online companies are allowed to expand. Silicon Valley is now often seen as an empire that tries to expand its power globally, and nation-states have started to fight back.

The rest of the world increasingly starts to develop homegrown tech solutions for one reason or another, which will likely make the pendulum shift. The market value of American tech firms isn't going to grow that quickly anymore, and the value of tech firms focussed on emerging markets will catch up.

The emerging markets companies mentioned earlier in this article already have considerable market caps – MercadoLibre USD 85bn, Ozon USD 12bn, and Allegro EUR 15bn. However, this trend is probably in a similarly early stage than the FAANG stocks in 2010. Valuations seemed relatively high back then, and fortunes had already been made. But the best was yet to come because the total addressable market was bigger than most people could have imagined at the time.

E-commerce as an example of this trend

E-commerce is a sector that has advanced significantly and where investors have already deployed a lot of capital. Yet, it will likely continue to generate fortunes because so many parts of the world still have so much catching up to do.

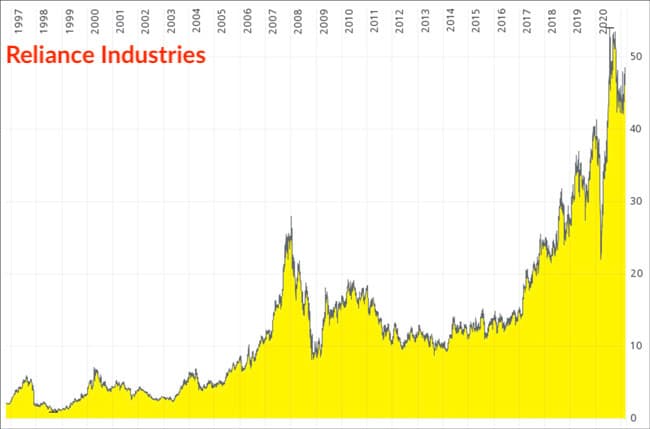

India has one of the lowest penetrations of e-commerce globally with just 5% of retail happening online. Only a third of the country's population is online, but even that makes India the world's second-largest user market (after China). The local tech giant to emerge was Reliance Industries (ISIN US7594701077), which through its subsidiary, Jio (not yet listed), has positioned itself for a leading market position. Facebook and Google have already realised that they cannot crack the Indian market themselves and instead used their financial might to take stakes in Jio of 10% and 8%, respectively. The stock price of Reliance Industries, long regarded as an Indian Old Economy firm, has performed more along the lines of a successful tech company. It's up five times over the past five years and could have a lot further to run over the course of the next five or ten years.

A world of opportunity across more sectors than anyone can keep track of

What's unusual about the times we live in are the scope and variety of available opportunities.

Potentially transformative innovations used to be a once-in-a-generation phenomenon. Think steam engines in the 19th century, or automobiles emerging at the turn of the 20th century.

Today, the pipeline is packed with game-changing trends:

- Artificial Intelligence (AI)

- Internet of Things (IoT)

- Big data

- 3D printing

- 5G, cloud services

- EdTech

- Augmented/Virtual Reality (AR/VR)

- and other industries.

Many of these sectors are still in their infancy even in the US and Europe, never mind in emerging markets.

For all of these sectors, less-developed parts of the world offer almost endless opportunities to increase productivity or revolutionise industries. The winners can create massive value for their financial backers.

Healthcare is an example where matters are at an earlier stage than e-commerce. It is one of the least digitised major industries even in the developed world, despite generating about 5% of the world's data. Throw in the fact that the population of emerging markets increasingly catches lifestyle diseases such as diabetes and obesity, which are very expensive to treat and manage. This development will make the clever use of technology even more of a priority in the developing world.

Plenty of room for innovation! (Image: Travel Stock / Shutterstock.com)

Also, telemedicine and AI diagnostics are precisely the kind of technology solutions where nation-states wonder if they'd want to allow foreign companies to control matters. How comfortable will nation-states be with having their population's health-related data rely on foreign firms? The national security provisions in the RECP trade agreement point the way. Then factor in these countries' growing number of entrepreneurs who fit the profile of founders like Gojek – internationally educated, rooted in their home country, and with access to the ever more globalised funding markets. It all goes back to the combination of regulatory regimes favouring local players and domestic entrepreneurs having the wherewithal to make it happen.

FinTech is another area waiting for the emergence of new success stories in emerging markets. FinTech companies currently handle just 5% of the world's financial transactions. Billions of people in the developing world remain unbanked, and FinTech could provide the solution to make them a part of the digital financial system. However, Fintech is also another obvious area for nation-states to develop more of a political and strategic interest. Following the 2008 financial crisis and the global pandemic, many countries will more actively evaluate the potential vulnerabilities of their domestic economies. The financial system will always be one of the first to pop up on the list of sectors considered for some form of national protection from international competition. Russia getting cut off from the US dollar banking system will have made many countries think twice about allowing foreign FinTech firms to dominate their domestic market. In July 2020, I wrote about Poland getting through the 2008 crisis relatively unscathed because (among other things) it had kept its domestic banks out of foreign control. Rightly or wrongly, these examples will get politicians elsewhere thinking.

Worldwide, there will be two to three billion incremental users joining the digital economy across emerging markets. For all the reasons stated above, more of them will utilise the services of companies that are not part of the FAANG group. The trend of domestically-grown tech champions emerging in Latin America, South East Asia, South Asia and Africa has only just started.

That's the theory of David Halpert, a fund manager and pioneering thinker behind much of this subject matter.

He is the man you need to follow if you want to develop a good understanding of the subject.

We are merely at the beginning of this new investment theme

If you google "Digital Decolonisation", precious little will come up.

The acronyms and catchphrases that describe an investment era can often be traced back to one insightful person bringing them into the public conversation.

The "Nifty Fifty" investment theme of the 1970s was started by a research note published by Morgan Guarantee Trust.

Antoine van Agtmael coined the term "emerging market" in 1981.

Jim O'Neill came up with "BRICs".

"FANG" (initially with just one "A") was coined by Jim Cramer, the host of "Mad Money" on CNBC, in 2013.

There is a good chance that David Halpert will become widely known for "Digital Decolonisation" and its shortened version, DigDec. He has even trademarked the acronym.

Halpert is the founder of Prince Street Capital Management, a fund management firm with offices in Singapore, Hong Kong, and New York. Since its founding in 2001, Prince Street has focussed on emerging and pioneer markets. During the past few years, Halpert has spent countless hours researching trends in and producing internal papers about Digital Decolonisation.

The wider public has not yet gotten to learn about it to any considerable extent.

So far, the only substantial interview that exists about DigDec is a February 2020 podcast with Halpert and Better Mousetrap NYC.

Listen to the interview with David Halpert of Prince Street Capital Management

As Halpert described it then, it was a 2016 meeting with the founders of Gojek in Indonesia that inspired the term:

"I started to observe a changing dynamic whereby emerging markets entrepreneurs chose to forgo personal gain and refused the sale of their companies to foreign tech titans as it was not in the best interests of their countries. The Trump administration’s decision to walk away from the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP) in January 2017 was a turning point in the course of tech geopolitics as emerging markets entrepreneurs could now partner with their governments to implement regulation that protected domestic digital assets and opportunities. China and Russia showed the way by fostering the emergence of local Emerging Markets Titans who offered local solutions, who benefitted from regulatory protection, and who leapfrogged foreign competitors."

Halpert and his team have since turned the idea of Digital Decolonisation into a "lens" – an analytical framework – through which they view investment opportunities.

In May 2020, Halpert launched the Digital Decolonisation Fund, with the aim to find distinct and undiscovered investment opportunities in this area.

Halpert's term may well become a well-known dictum in the financial industry. Any new such trend takes a decade to take hold, but the potential is vast. Multi-billion tech firms are likely to emerge in Egypt, Brazil, Argentina, Kenya, South Africa, Turkey, Mexico, Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Nigeria – to name just some of the countries that have a sizeable economy or population. There could also be regional players, just like MercadoLibre managed to expand across a range of smaller Latin American countries which gives the group critical mass despite the relatively small size of some of these nations.

Inevitably, there'll also be disappointment and frustration along the way. However, it does seem that Digital Decolonisation is shaping up as a trend where setbacks will only provide further opportunities for investors to join.

There might also be plenty of variations of the theme along the way.

Undervalued-Shares.com Lifetime Members have already witnessed as much in my May 2020 report on PBKM (ISIN PLPBKM000012), a Polish stem cell bank. PBKM first rose to prominence as a high-tech player in its domestic market, but subsequently expanded to dominate the Western European market and became the world's #3 in its sector. Western tech firms used to buy up their competitors in emerging markets. Now, the opposite has started to happen!

For sure, there'll be more opportunities coming out of this investment theme than we can even imagine right now.

How can you find them - and (probably even more importantly) early on?

Thanks to a mutual friend and Lifetime Member, Halpert generously granted me access to his team and research. I was able to pick his brain for this three-part series to help other investors educate themselves about these opportunities.

Next week, you'll get to read about the kinds of companies you should look at.

Stay tuned for more.

Blog series: Digital Decolonisation

There's more to "Digital Decolonisation" than this Weekly Dispatch. Check out my other articles of this three-part blog series.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post: