It's fair to say the Catholic Church would not exist in quite the state it does today, had it not been for one individual who single-handedly changed its financial fate.

For over a quarter of a century, fund manager Bernardino Nogara had made BILLIONS for his employer (in absolute sums measured in today's purchasing power).

He bought and sold stock in countries near and far, did arbitrage between bonds and currencies, and hedged by buying gold and stashing it in secure locations overseas. He was a speculator, an activist investor, and a long-term strategist all wrapped into one. In today's world, you would have expected him to live in New York or London, rather than a prestigious Papal apartment in the Vatican.

Yet, you are unlikely ever to have heard of his work.

The origins of today's Weekly Dispatch date back to the 1930s, and everyone featured in this article has long been dead.

Still, Nogara's work continues to teach useful lessons even today.

Sit back, pour yourself a mulled wine, and enjoy this exclusive Christmas special by Undervalued-Shares.com.

Today's Weekly Dispatch takes place in the world's smallest independent state.

A rags to riches story

Everyone knows that the Vatican of today is the world's smallest independent state. Few are aware, however, how it came into its legal existence less than a hundred years ago and why it reaped a financial windfall at birth.

To make sense of it all, it's important to briefly go back over a thousand years.

During the 8th century, the Papacy effectively became the sovereign ruler of large parts of Italy, filling in a vacuum left behind by the decline of the Byzantine Empire. Somewhat counterintuitively, the Catholic Church grew to be both an ecclesiastical and a temporal power. As an ecclesiastical power, it rules over the world's Catholics while as a temporal power, it rules over large parts of Italy quite like any other government.

However, by 1861, the Papal States of Italy had lost most of their territory to the rising Kingdom of Italy created by the House of Savoy. At the time, all that was left of the Papal States' former glory were 12,667 square kilometres of land (about 4% of Italy's landmass) with 700,000 inhabitants. Even this final stronghold of temporal power was lost when its remaining 13,000 soldiers were challenged by the vast army of King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy. The Vatican ordered its troops to put on a short battle just to evidence its resistance, and then wave the white flag to avoid serious losses. All that the House of Savoy left for Pope Pius IX to reign over were St. Peter's Basilica, the Papal residence and 23 related buildings.

For the coming 59 years, Pius IX and his successors effectively remained prisoners in the Vatican. In protest against the annexation of their territory, none of the reigning Popes set foot outside of the narrow confines of their remaining territory until 1929. All these years, as a means of retaliation, the successive Popes forbade all Catholics, on pain of excommunication, to vote in Italian parliamentary elections or stand as candidate. The occupation of the Papal States, combined with the strong moral position that the Catholic Church held among Italians, made for an uncomfortable political situation, which was further complicated and inflamed by virulently anti-clerical political groups that operated in Italy at the time. Tensions were so high that when the corpse of a deceased Pope was transported outside of the Vatican in 1878, a mob of anti-clerics stopped the funeral procession and threatened to throw the remains of the Holy Father into the river Tiber. It's safe to say that no one had a good time; equally, no one knew a way out of the situation. As the saying goes, it's easy to start a war but difficult to end one.

In a clear sign of guilt, Italy offered the Papacy an annual stipend of 3.25m Italian lire, payable until eternity. This represented a massive sum at the time, and it was offered during an era when the Vatican was truly starved of cash. Even so, three subsequent Popes refused to accept a single lira as payment. To demonstrate its seriousness, the Italian state deposited the money in a bank account each year. While millions were accumulating in an untouched bank account, the Vatican was so broke that the Pope had to put up with rats infesting the entire Vatican and mildew covering invaluable art work. At one point, the Vatican only had enough cash left to fund its operation for one more day.

The stalemate broke when the most unlikely of characters got involved. The fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini, would not have appeared like a potential saviour of the Vatican. He held such rabid anti-clerical feelings that he once authored a pornographic novel called "The Mistress of the Cardinal", purely out of spite. The Pope, in turn, had called him "the devil". However, Mussolini was also known to be superstitious. During public appearances, he often unabashedly put his hand into his pocket to tap his private parts for good luck and to protect himself against "the evil eye". Presumably, Mussolini suffered from the kind of paranoia that any respectable dictator would suffer from. He didn't want to have God's earthly representative against him, and sensed political gain from freeing the Papacy from its tiny prison.

On 11 February 1929, Mussolini went to the Vatican to sign the Lateran Pacts, an agreement that his representatives had negotiated during the preceding two and a half years. Named after the Lateran Palace where it was signed, this was really three agreements wrapped together:

- The Lateran Treaty, which provided for the creation of a new sovereign State of Vatican City.

- The Financial Convention, which granted compensation payments to the Church to make up for the loss of territory and associated loss of income.

- The Concordat, which gave the Vatican special powers and privileges. These mostly related to the management of the Vatican's day-to-day affairs, such as the ability to pay tax-free salaries to Italian citizens.

Mussolini (centre) and representatives of the Vatican at the signing of the Lateran Pacts.

The Lateran Pacts granted the Vatican what is today its sovereign territory. (Contrary to popular belief, this isn't just the area immediate around St. Peter's Basilica, but extends to a range of buildings elsewhere. Because of these outlaying extraterritorial buildings, the Vatican's landmass is actually three times the size that is commonly quoted – but it's still only 1.73 square kilometres or 0.67 square miles.)

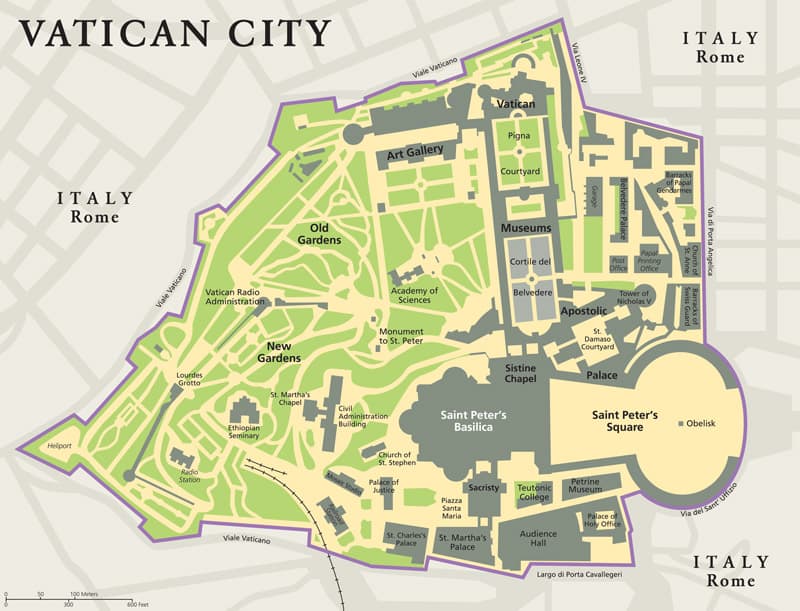

As financial compensation, the following was agreed:

- Italy would pay the Vatican the sum of 750m Italian lire in cash.

- Additionally, the Vatican would receive Italian government bonds with a face value of 1bn Italian lire, and an initial interest rate of 5% p.a.

- Italy would shoulder the salaries of all Catholic priests stationed on its territory.

The financial agreement was as wonderfully short as contracts and treaties used to be at the time. In the day and age before lawyers and bureaucrats ruled the world, such a history-making pact fitted on a single page!

The Financial Convention of 1929 (source: Lateran Pacts).

Even back in those days, Italy had a slightly sketchy reputation as debtor. When the bonds were issued to the Vatican a few months later, they already traded as low as 78% of their face value. It couldn't have been clearer that the Vatican needed to get on top of managing its new fortune if it wanted to ensure it didn't slip away.

The cash payment did arrive on time, and provided the foundation for the Vatican to create its own investment portfolio. It proved transformational for the further fate of the newly created Vatican State – and by extension, the Catholic Church as a whole.

The private banker who saved the day

The sum of 750m Italian lire at the time translated to USD 81m. It's difficult to get your head around the purchasing power this figure had back then. To put it in context, during the decade preceding the Lateran Pacts, the Vatican had run on annual budgets ranging from USD 1-2m.

Using the one-off windfall, the Vatican wanted to create a financial strategy that would see it regain true financial independence. As large an amount as possible was supposed to be invested for income and capital growth, although another part was also destined to go into urgently necessary construction work on the Vatican's newly secured sovereign grounds.

The man who played a major role both in the investing of the money and the management of capital expenditure was one Dr. Bernardino Nogara.

Dr. Bernardino Nogara (1870-1958).

An engineer by training, Nogara had originally managed mining projects in Wales, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire. During his time in Istanbul, he was appointed a representative of the Italian Banca Commerciale, then the country's largest private bank. In his new role, Nogara got involved in a committee overseeing the restructuring of the Ottoman Empire's debt. His family had close links to the Catholic Church, which is why he got to befriend the Pope of the time, Benedict XV. In 1914, Benedict XV received a tip-off from Nogara that Ottoman-issued bonds were a good investment. The Pontifex invested through his personal account and made a tidy profit. What reeked of insider trading was probably just that, and it set up Nogara for a later role in the Vatican. Even after Benedict XV's demise in 1922, Nogara remained on the radar of the Vatican's authorities. Along the way, he was involved with the negotiations of Germany's compensation payments following the First World War.

Much of this history is clouded in incomplete records, hear-say, and contradicting source material. Allegedly, Nogara was already involved in the Vatican's financial dealings during the time the Financial Convention was negotiated. Given his prior involvement in negotiating such agreements, this would have made sense, but it was never confirmed. In any case, when the windfall arrived in the Vatican's bank account in June 1929, the reigning new Pope, Pius XI, entrusted Nogara with the management of the cash.

Nogara's primary job was to find good investments to generate ongoing income and long-term capital gains. Along the way, he was also involved with the managing of the overall financial affairs of the Vatican. This was a time when the Vatican did not have as much as an annual budget or an accounting system, and controls over the organisation's finances were spread across several sub-organisations. Nogara started to bring some order into the chaos. Some claim that Nogara became "the State Treasurer of the Vatican", while other historical resources negate these claims, attributing him a more limited role.

In any case, Nogara went to work to invest the funds. As history was going to show, he set out to ensure that the Vatican would never again fall on hard times financially.

The difficulty of researching Nogara's lifetime work

Evaluating Nogara's performance is anything but easy.

The Vatican is one of the world's most written-about organisations, but it's also one of the least transparent. Inevitably, given its role as earthly manifestation of one of the world's largest religions, its coverage in both the media and academia is fraught with ideology and ulterior motives.

Anyone who wants to delve into the broader subject of the Vatican's overall wealth will find a plethora of books with claims including the fantastical and the outrageous. Some claim the Vatican literally owns the world – when, as we all know, it's actually owned by the Rothschilds lizard people. I purchased just about any book on the subject that sounded vaguely relevant, and concluded that most of them deserve to go straight to the recycling bin.

A rare 1st edition of one of the crazier books.

The difficulty in assessing Nogara's performance is inherent to the ways in which the Vatican operated at the time. Nogara was one of the Vatican's uomini di fiducia, "men of trust", and he operated in a particular manner that was commensurate to the trust placed in him. Much of what the Vatican did was not fixed in writing, but done verbally only, to avoid leaving behind evidence that could leak to the media or opponents. One of the more serious books described the Vatican's "typical procedure" for dealing with requests for information about its finances: "No direct answer, nothing put in writing, no indication of who exactly was responsible for the refusal."

"The Vatican Empire", a 1969 book by Nino Lo Bello, went to great lengths to get to the bottom of the Papal wealth. It described Nogara in a way that is consistent with much other source material:

"Few anecdotes can be told about this financial fox, for Nogara successfully managed to keep almost everything he did a secret – even from his superiors, who trusted him implicitly. A ranking Vatican official once said: 'Nogara is a man who never speaks to anybody; nor does he tell the Pope much, and I would guess, even very little to God – yet he is a man worth listening to.'"

For all his secrecy at the time, Nogara did leave behind some records. On average, he met with the Pope every ten days to discuss the investments as well as the general state of the world. Nogara kept a diary of his meetings with the Pope since 1931 (but not before), which gradually became available to researchers and authors.

The single most credible and detailed of these writings happens to be a book available in German only. "Finanzen und Finanzpolitik des Heiligen Stuhls" (Finance and financial policies of the Holy See) by Hartmut Benz is based on someone's Master's thesis and was published as an academic book in 1993. Another outstanding example of credible research on the subject is the 1973 book "Vatican Finances" by Corrado Pallenberg.

There'll never be audited, annual performance figures for the period when Nogara oversaw the investment portfolio. Outside of the lack of records, there was also an immense amount of intermingling of investment funds with other financial needs of the Vatican. I doubt anyone could untangle this web of finances, even if all existing documents were made available.

The good news is, there are several credible resources that allows us to make a judgment about the order of magnitude of Nogara's returns.

Nogara made billions

Pope Pius XI held his protecting hand over Nogara to ensure he was not caught up in Palace politics or held back by bureaucracy. However, internal politics did get to Nogara eventually, if only briefly. When Pius XI died in February 1939, internal machinations immediately tried to oust Milan-born Nogara from his powerful position to have him replaced with someone from Rome. Nogara allegedly didn't manage the financial affairs properly, and a special commission of Cardinals was appointed to investigate his work.

Upon finishing their work, the Cardinals reported unanimously that Nogara had grown the investment capital by a factor of 20 over the past ten years. This was a stunning performance given that the 1930s had seen the Great Depression and much political turmoil in Europe and elsewhere. Nogara had answered all questions of the Cardinals and was subsequently left alone again to pursue his work without much interference. His small team of barely a dozen key people was hitherto known as the Vatican's "Commando Force".

Other credible figures for a longer period date back to the mid-1960s and were researched by Britain's Economist and Switzerland's Finanz & Wirtschaft. Neither one of them were able to give a precise figure for the annual performance of the Vatican's stock portfolio, but both managed to establish an order of magnitude of the portfolio's absolute size:

- Finanz & Wirtschaft believed that the Vatican's stock portfolio had grown to make up 7-10% of the Italian stock market's entire market cap. This was all the more remarkable when considering that the Italian exposure in the Vatican's overall investment portfolio was just 10% at the time.

- The Economist estimated that 10-15% of the Italian stock market could be in the hands of the Vatican. As the world's oldest weekly magazine reported at the time:"The Vatican could theoretically throw the Italian economy into confusion if it decided to unload all its shares suddenly and dump them onto the market."

Historical figures about market caps and purchasing power are difficult to obtain and even more difficult to grasp. However, Italy was then the world's fifth largest economy, and owning anywhere from 7-15% of all public companies of such a major country would have represented a major financial coup for any organisation. It was even more remarkable when considering that 40 years prior, the Pope of the time didn't even have any spare cash to combat the rat infestation.

Nogara is the man who deserves to be credited with the incredible growth of the Vatican's investment portfolio. One of the more sensationalist books called him "the financial wizard of the Vatican", and for once, this claim actually seems justified.

After Nogara retired in 1956 due to ill health, his former number two, whom he had poached from Credit Suisse, took over. The team continued to have access to Nogara's advice until his death at age 88 in 1959, and it reportedly stuck to his methodology religiously. Even after Nogara's ascent to the wild blue yonder (where, without a doubt, St. Peter will have personally held open the gate for him), his well-oiled investment machinery will have added yet more billions of wealth to the Vatican's coffers.

The question is, how did he do it?

What can we learn from him to help navigate today's treacherous financial markets?

I sifted through the confusing and at times contradicting literature about Nogara's work. The resulting distillate is a list of ten features that make up the pillars of his investment strategy.

1. No constraints

Nogara's condition for taking the job was not to face ANY constraints in how he was going to invest the money. In particular, Nogara did not want to be hampered by religious or doctrinal considerations.

Speculating in government bonds of Protestant Britain? No problem!

Nogara also got the Vatican to agree that he was free to invest anywhere in the world and through any means necessary.

Last but not least, he would not have to show any short-term performance figures.

Nogara had himself become "the dictator of the Vatican's funds, who answered to no one – not even to the committee of three Cardinals which, theoretically, supervised the Special Administration of Vatican funds."

Nogara was, in the true sense of the world, one of the Pope's uomini di fiducia, men of trust. The fact the he was deeply religious and had several close family members who also worked for the Catholic Church probably helped to attain this status.

Nogara was free to invest both for long-term and short-term gain, using virtually any financial instrument.

With this mandate, he could seek out the world's best opportunities. The ONLY factor that mattered was, what is good for the portfolio?

2. Distressed investing

Even though it's difficult to quantify its exact effect on the portfolio, there is considerable anecdotal evidence that Nogara boosted his returns by investing in distressed opportunities. Some of them, at least, subsequently produced spectacular returns of many times the original investment.

One of the more famous and well-established examples is Nogara's backing of a government scheme that helped to bail out Italian banks. In 1933, large corporations in Italy weren't able to repay outstanding loans to banks, which threatened the very existence of the Italian banking sector. The Italian government of the time decided to create a public/private entity to stabilise the situation. The Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale ("IRI") got one lira of government funding for each 12 lire of private capital it managed to raise, and the public was incentivised to invest by promising a tax-free return. No one knows how much the Vatican invested, but it is widely believed that it was the single biggest investor in the scheme. Reportedly, Nogara sold a good chunk of the Italian government bonds that the Vatican had received from Mussolini in 1929, and reinvested the proceeds in IRI instead.

IRI's history is well-established, since it became Italy's largest conglomerate with stakes in many of the country's largest companies, including Alitalia, Alfa Romeo and Telefonica. The resulting sprawling group was dissolved only in 1992.

The Vatican's massive stake in the Italian economy, as revealed in the 1960s, will also have been due to its investment in Italian industry at a time when these companies were on the brink of insolvency.

Not unimportantly, the Vatican's large interest in IRI will have given Nogara another important tool, that of a…

3. Network of informants

As representative of the Vatican and with massive assets to invest, Nogara will have had unprecedented access to almost anyone and everyone.

He further increased his access to information by placing his own men of trust – uomini di fiducia – on the boards of companies.

Insider trading was legal in Italy until 1991, and Nogara will have made use of his privileged access to corporate information on many occasions. Through his involvement with financing IRI, for example, he sometimes heard of upcoming corporate action at some of the portfolio companies, which he then utilised to place further bets by buying equity in these companies before the market got wind of the news.

Little of this was ever spelled out anywhere, but it's all clear as day when reading through the historic material about Nogara's work.

4. On-the-ground research

Nogara's diary shows that he was "always travelling".

Much as he had his men of trust in key positions everywhere, Nogara travelled all over the place to personally tend to his investments in a variety of ways. He will undoubtedly have kept close personal relationships with staff at important banks (see next point), well-placed informants, and leaders of enterprises that the portfolio was invested in.

(Incidentally, this is a recurring theme among many successful investors, including "Nick Roditi – the phantom billionaire".)

5. World-class banks

The more sensationalist reporting about the Vatican's finances loves to point to links to the Rothschilds – and rightly so.

Not only is it well-documented that the Rothschild banking family at least on one occasion lent money to the ailing Vatican when it was in times of need, but Nogara chose to actively make the famous banking family a part of his operation.

When he set up the infrastructure for investing money, Nogara opened bank accounts with a number of financial institutions that were going to be key for his investing: Hambros in London, J.P. Morgan in New York, and Credit Suisse in Switzerland. The banking operations of the Rothschild families in Paris and London also got some of his business.

On what basis did he choose these banks?

Nogara wanted to ensure he got first-class service even during difficult times and for complex transactions.

At times, he channelled money through several banks to circumvent the kind of capital controls that much of the world was under at the time.

On other occasions, he needed access to trading in exotic locations to make use of arbitrage opportunities.

With his network of accounts at banks that were globally connected and had a deeply rooted culture of resolving issues for clients, Nogara usually found a way around potential restrictions – such as wanting to invest in US industry during the Second World War, when Mussolini's government blocked Italians from investing there.

6. Active management, including activism

It's difficult to draw the line between active management and outright activism in Nogara's work.

Nogara was an active portfolio manager who sought out opportunities to generate alpha, but he also engaged in activism on the odd occasion.

Given his shadowy operations, it's a bit more difficult to get a handle on Nogara's role as activist. While some sources play down the size of the Vatican's stake in individual companies, others point out that Nogara bought a blocking minority in at least 12 public Italian companies.

One famous case was the 15% stake that Nogara bought in Società Generale Immobiliare (SGI) in 1949. After the Vatican became the single largest shareholder, Vatican representatives started to pop up on the board of directors and take control of the operation.

Nogara was known to have taken an active interest in controlling land and developing real estate. Following the Second World War, Italy had a huge need for more housing. SGI bought pastoral land near Rome and became the country's largest developer of new residential property. With high likelihood, Nogara will have played a role in SGI's landbanking, given that Catholic organisations owned about 25% of the real estate in and around Rome.

SGI rose to become not just one of Italy's largest real estate firms, but one of the world's largest. Following the end of the Second World War, it extended its activities to North and South America. Even today, SGI's footprint in Italy's real estate market remains visible. Come to think of it, Nogara had purchased the stake for a paltry USD 1.5m.

The Vatican sold its stock for many times its initial investment in the late 1960s, but SGI continued as a mythical figure in Italy's corporate lore. A possible reference to the company, by the name of "Internazionale Immobiliare", featured in the movie "The Godfather, Part III".

Nogara was dubbed "the empire builder of the Vatican", but he also actively built companies by helping them get the right pieces of the puzzle together.

7. Sector competence

Nogara invested all over the place – quite literally – but he also had his preferred sectors.

Many of his largest investments were in banks, insurance companies, and infrastructure.

That's where he felt most at home, and his deep knowledge of these sectors helped him de-risk his investments.

8. Risk management including geopolitics

Nogara invested the portfolio at a time of great political turmoil. Capital controls preventing the free flow of money were the norm rather than an exception. Also, the risk of wars and government bankruptcies loomed large.

To protect his portfolio, Nogara engaged in risk management that included keeping an eye on geopolitics.

The notion of hedging was in its infancy at the time, and it usually involved gold. Nogara invested in physical gold as a hedge against the Second World War, and he had it stashed in the underground storage of the Federal Reserve Bank in New York.

It's not entirely clear how much physical gold Nogara invested in, but there is credible evidence that he placed a huge bet on it at a time when the gold price was USD 35 per ounce. It's also likely that the Vatican kept this investment until at least the 1970s, which enabled successive Popes to sleep soundly in the meantime, knowing there was a real emergency investment stashed in the kitty.

Circumventing currency controls, anticipating major geopolitical developments and trying to manage the minefield of resulting risks were part and parcel of Nogara's work.

9. Long-term compounding

Even though he was an active manager and even a short-term speculator at times, Nogara often stuck to investments for years or even decades.

The stock market crash of 1929 resulted in US stocks trading at record-low prices, and Nogara built a portfolio of US stocks that included the likes of IBM, General Motors, Bethlehem Steel, RCA and TWA. Many of these companies fared very well during the war economy of the 1940s, and the US economy continued booming during the 1950s.

As an entry in Nogara's diaries revealed, these blue-chip investments eventually "provided one of the biggest pillars for the Vatican's post-war financial strength". All the more so since they allowed the Vatican to keep money in US dollars instead of Italian lira, whose exchange rate was diluted by about a factor of 30 as a result of the war.

At times, something as simple as picking the right region of the world and keeping clear of constantly chasing new ideas can produce stunning results.

10. Taxation freedom

Capital accumulates much faster if you don't have to share parts of the gains with the tax man.

The Vatican had gained freedom from all taxation as part of the Lateran Pacts.

In 2008, then-Pope Benedict XVI railed against "tax havens for robbing poor". He even "laid blame for the global financial crisis at door of 'offshore centres'".

Mind you, the Vatican has long been an offshore centre itself!

When Italy attempted to tax the dividends that Italian companies paid to the Vatican in the 1960s, the Vatican went to great lengths to avoid paying up. It even threatened to dump all of its Italian holdings on the market, which came at a time when Italian stocks had already suffered a 40% decline. The prospect of Italy losing the massive investment of the Vatican led to the tax issue getting resolved in the Vatican's favour.

To this day, the Vatican is a giant tax haven. It might portray itself as something else, but it simply is. The Concordat signed in 1929 has given the Vatican a unique ability to get away with paying little in taxes.

During the decades of accumulating wealth by participating in financial markets, the ability to do so effectively tax-free will have further fuelled the speed at which the capital was compounding.

"Do as I say, not as I do" – the Vatican's position on tax freedom (source: The Guardian, 7 December 2008).

Vital lessons for today's world

Without a doubt, Nogara was one astute investor. His work will have made the Vatican billions measured in today's purchasing power, and this wealth will still be producing income for the Vatican today.

The obvious question is, where is all that money today and how much does it amount to?

It's impossible to say. The Vatican provides glimpses of its wealth, but its entirety is cloaked behind a veil. The assets managed by the infamous Vatican Bank (which was also a brainchild of Nogara) amount to a comparatively paltry EUR 5bn, as can be seen from its publicly available accounts. However, it has always been the strategy of the Vatican to appear both poor and rich at the same time. Rich, so that it retains an aura of wealth and the influence that stems from it. Poor, so that it doesn't come under attack for hoarding money when the world's poor are in desperate need.

Ultimately, the Vatican is only one part of the countless organisations that make up the Catholic Church. The ownership of real estate in and around Rome illustrates the situation. In the 1970s, the Vatican fervently refuted media reports that it owned 25% of the built real estate of the Eternal City and pointed to its ownership of a comparatively modest few dozen properties in the region. However, other parts of the Catholic Church will have owned massive amounts of real estate in Rome, accumulated through inheritances and purchases. The Catholic Church practiced the art of being a fully decentralised organisation many hundreds of years before the crypto bros tried to sell that idea as theirs.

Having trawled through piles of books on the subject matter, I am inclined to believe that the Catholic Church may well be the largest asset owner and wealthiest organisation on the planet. However, no one will ever know for sure how rich the Vatican and the Catholic Church really area. The changing Zeitgeist has forced the Vatican to pay lip service to calls for transparency, but in actuality it still adheres to a principle laid out in the gospel: "Let not thy left hand know what that right hand doeth."

The financial gains from Nogara's work will have been dispersed into many different sections of the Vatican and the wider Catholic Church, but the wisdom that we can glean from his work remains right there.

Just some aspects of Nogara's strategy that any private investor can learn from or be inspired by include the following:

- Refusing any constraints on where and how you can invest? I'd call that one of the cardinal rules you need to adhere to in order to grow and protect your wealth.

- Building up specific sector competence? Always a good idea!

- Educating yourself about geopolitical risks and how to avoid issues such as custody risk? During the tumultuous 2020s, these are subjects that everyone needs to be aware of.

As this review of Nogara's work shows, many aspects of being successful in investing don't really change over time. An organisation that has survived 2,000 years of humanity's chaos will be first to realise that there are timeless principles that never change.

No other single individual, Pope or Cardinal ever gave as much impetus and muscle to Vatican finances as Nogara. A fitting epitaph was uttered by Cardinal Francis Spellman, then archbishop of New York, when he heard of Nogara's death in 1958: "After Jesus Christ, the most important thing that happened to the Church is Bernardino Nogara."

Indeed, Nogara deserves to be remembered by the investing community for stoically adhering to timeless principles and creating incredible investing success as a result.

Looking for a last-minute gift?

Memberships make great gifts!

Treat your friends or colleagues to an Undervalued-Shares.com Membership this Christmas.

For just USD 49, it's quite the present: 10 extensive research reports every year, archive with all 35+ past research reports, updates on previous research reports, and email alerts for reports and updates.

You'll be hard-pressed to find a better deal elsewhere.

Just email me, ask for a gift voucher and we'll get the ball rolling – guaranteed in time for Christmas, of course!

Looking for a last-minute gift?

Memberships make great gifts!

Treat your friends or colleagues to an Undervalued-Shares.com Membership this Christmas.

For just USD 49, it's quite the present: 10 extensive research reports every year, archive with all 35+ past research reports, updates on previous research reports, and email alerts for reports and updates.

You'll be hard-pressed to find a better deal elsewhere.

Just email me, ask for a gift voucher and we'll get the ball rolling – guaranteed in time for Christmas, of course!

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post: