Dinosaur skeletons – an emerging asset class?", I asked in March 2023. Many of my readers were amused.

By late 2024, their amusement had turned to envy. Hedge fund billionaire Ken Griffin had forked out USD 45m for a T-Rex skeleton – the most ever paid for a dinosaur.

One entrepreneur even launched an investment company for dinosaur bones.

Are we going to see a similar development for human remains?

Between 2018-2024, the value of ethically sourced human skulls has appreciated by over 50% p.a.

Even more surprising, there could be a catalyst to turn this into a fast-growing, multi-billion market.

A new investment trend in the making.

Yours truly researching this trend at The Bone Museum in Brooklyn.

Why not?

The idea of collecting human remains might sound morbid, but is it really?

Who has never taken a curious, close-up look at an Egyptian mummy in a museum?

The Paris Catacombs hold 6m human bones and attract half a million tourists per year.

One popular episode of Indiana Jones saw him hunting for elongated Peruvian skulls.

Once you start digging into the subject matter – forgive the pun – you'll be surprised in how many places human bones turn up.

It shouldn't surprise us, though. If anything, human bones are utterly abundant.

According to demographic estimates, 109bn people have lived and died over the last 192,000 years.

Globally, 150,000 people pass away every 24 hours.

If thrown into the ground, human skeletons decay in as little as 25 years. Hot, wet, and acidic soil literally eats them up. However, internment in a coffin and many other factors can favour their preservation. In fact, the simple act of burial has done more to preserve large amounts of human bones than any other phenomenon in the natural world.

You could say that skeletons are the least intimidating ways to engage with the dead. Without hair, skin, or eyeballs, there are fewer tangible reminders of the living human. What's more, bones tell us how someone has lived and died.

Given their durability, human bones lend themselves to collection.

In the second half of the 18th century, the Western world saw a frenzy for collecting, analysing, and exhibiting human bones. The best specimens became highly sought-after artefacts for both scientific research and public display. Private investors bought them for their collections, and having a "cabinet of curiosities" was de rigueur among well-heeled British and American gentlemen. The trend lasted decades and culminated in ever-progressive California opening the "Museum of Man", which showed the largest exhibition of human skeletons ever presented to the public up to this point.

Times have changed, and more recently, collecting human bones existed only in a niche.

However, (almost) anyone can get into it. You can purchase skulls, bones, and complete skeletons legally through specialised online shops in countries such as the US, the UK, Germany, and Switzerland. Only a few states in the US have outright banned the trade of human skeletons. As far as the US is concerned, if a body wasn't dug up in the US, didn't belong to a US citizen or a Native American, and didn't come from a human who was assaulted or killed, no federal law exists to ban or prosecute the activity.

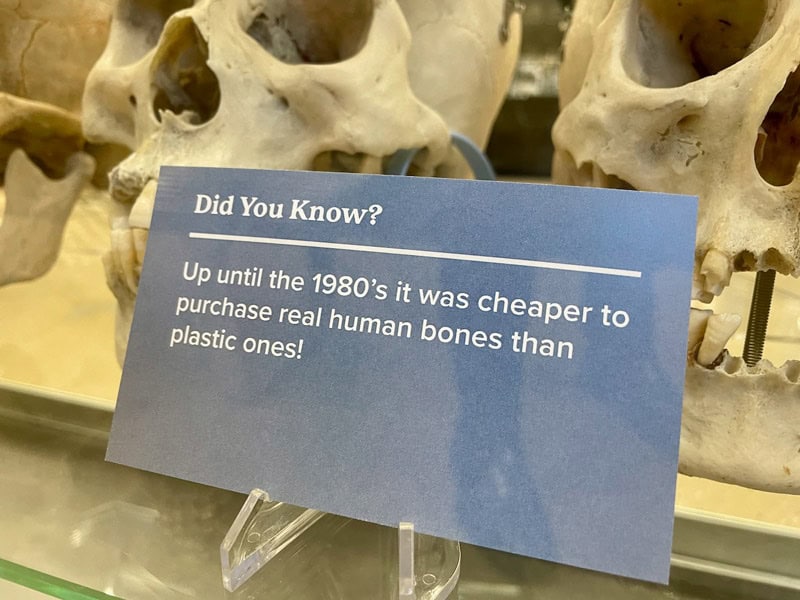

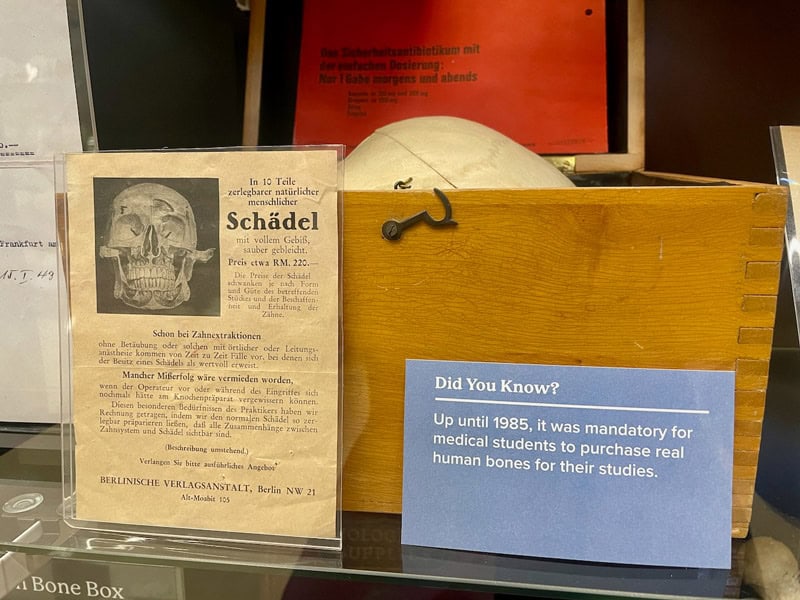

Getting your hands on human bones has long been important for some professions. E.g., medical students will find that only by looking at real bones – as opposed to plastic replicas – can they truly learn their profession. Until 1985, it was mandatory in the US for medical students to buy their own human bones for study. At the time, most of these bones came from India and were cheap to acquire. Today, doctors retiring or heirs finding these objects in the possession of their deceased loved ones are among the major source of rare, high-quality human bones for purchase.

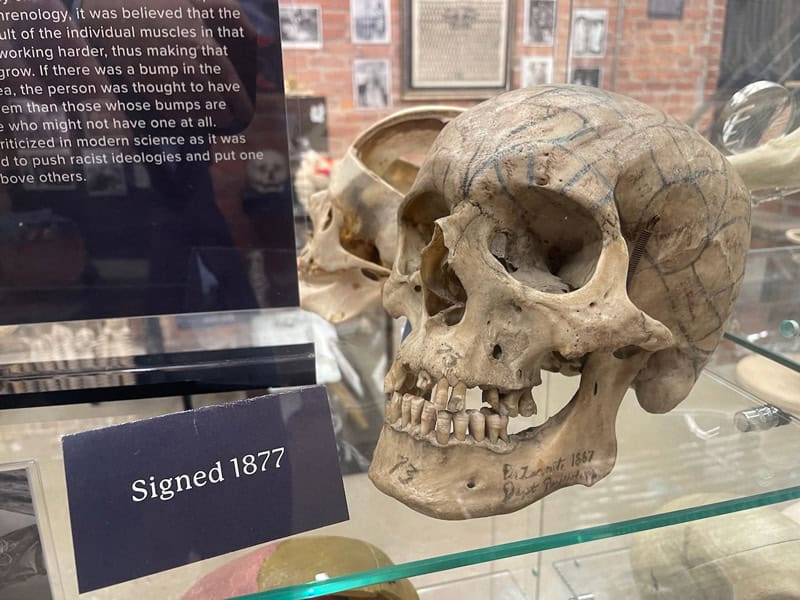

Source: The Bone Museum (photo by Swen Lorenz).

Of course, you wouldn't want just any old bone. As a collector – or investor – you'll be looking for something else.

Just what that is is something I learned more about when visiting The Bone Museum. Newly opened and located in New York's hipster district, Brooklyn, the museum is trying to take osteology – the study of human bones – into the 21st century and the public limelight. Its mission is to destigmatize osteology and provide an educational platform for understanding the history, science, and cultural significance of human skeletal remains.

The museum is about the size of someone's living room, but it has had massive impact. On TikTok, some of its videos have clogged up millions of views, while on Instagram, it has amassed nearly 700,000 followers. While I was there, a steady stream of – mostly younger! – visitors came in.

The studying of, marvelling at, and collecting human bones seems a hit with a growing percentage of the younger generation.

I predict that it's about to get much, much bigger!

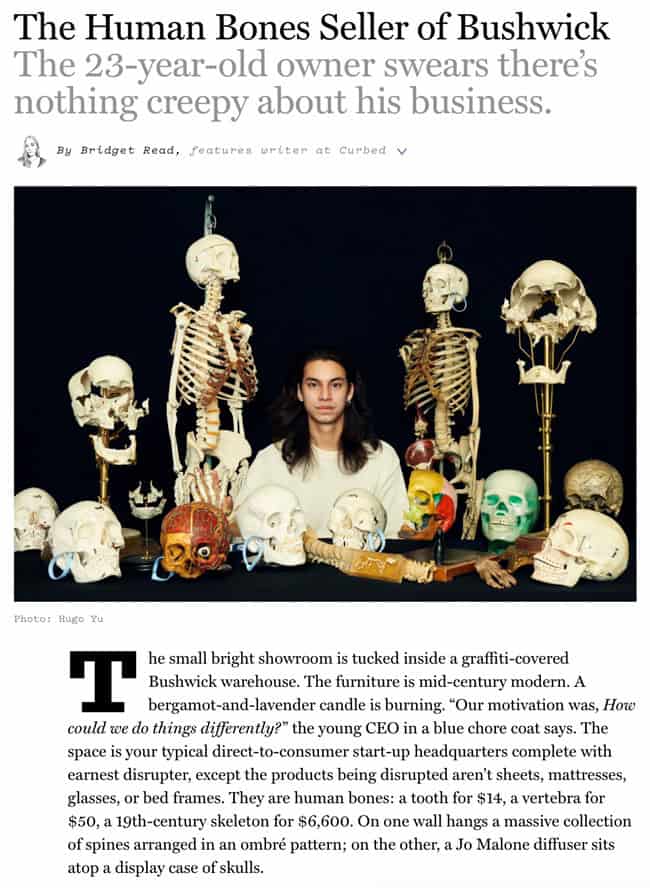

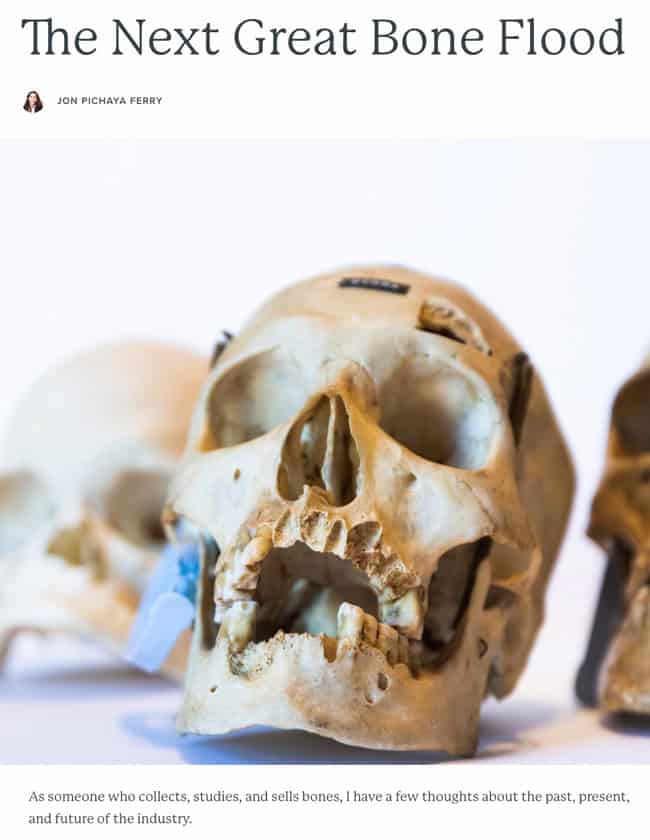

Source: Curbed, 7 June 2023.

The New Yorker who is re-inventing osteology

Museums and exhibitions of human bones are nothing new.

When large, public natural history museums were created in the mid-19th century, they usually included a collection of human skeletal remains. There was little hesitation to put them on public display, given that these museums were almost always set up to further popular education. We all have bones inside us, so what could be wrong with exhibiting and explaining what makes us human?

Large museums with suitably large collections of this type are too numerous to name.

A few noteworthy examples include:

- National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C.: it holds so many skeletal remains that staff reportedly refer to parts of its collection as "the skullery".

- Museum of Us, San Diego: after changing its name from "Museum of Man", the museum still holds the remains of 5,000-8,000 people.

- Mütter Museum, Philadelphia: an institution that wants to help the public appreciate the mysteries and beauty of the human body.

- Musée de l'Homme, Paris: France's leading anthropological museum gathers everything that defines the human being.

- The Royal College of Surgeons of England: its collection contains thousands of specimens of skulls, jaws, and teeth from humans.

One common denominator among these old-school museums is the controversy they have recently had to deal with.

During the heydays of large Western museums building their collections, ethical standards for sourcing specimens were lacking or even non-existent. Human remains were collected without asking for permission, and often enough involved stealing religious artefacts or picking up the pieces (literally) of violent conflicts.

Over the past years, museums have come under public pressure and caved in to criticism. Several large American museums agreed to remove all human bones from public display, improve the storage facilities where the remains are kept, and figure out which remains should be reburied, repatriated, or reunited with family – ahead of potentially returning with a cleaned-up collection for exhibition.

Source: The New York Times, 15 October 2023.

These issues ARE difficult. Would we object if our ancestors' skull and bones were displayed for the amusement, horror, and enlightenment of the public? Would you want your wayward Uncle Harry showcased in a museum to demonstrate the lesions and scars of syphilis?

These controversies do trickle through to the collectors' market for human bones. Just recently, a British auction of a range of tribal skulls was called off after a public call by Indian politicians to have the specimens returned to their native territory.

These issues are likely going to remain complicated for at least some more years. Anyone who collects or invests needs to pay attention to this issue, but it's also part of the attraction, because regulating this market will inevitably lead to a thinning out of supply. Speak of a market heading for scarcity by public order – that's what you are likely going to see in this sector.

Source: The Telegraph, 9 October 2024.

The Bone Museum in Brooklyn also faced controversy, but it had a clean sheet to start with and handled the delicate matter much better.

The museum opened its doors in 2022, and it benefited from its founder being a photogenic, personable 24-year-old who wanted to bring the world of start-ups, digital media, and disruption to the world of human bones.

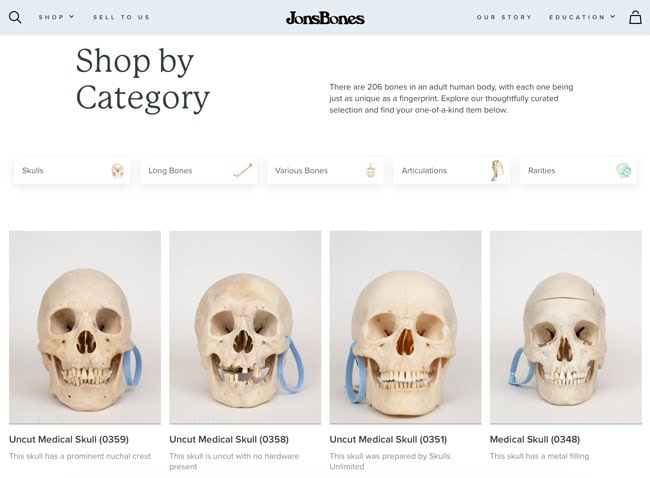

Jon Pichaya Ferry initially set up a business to supply human bones to medical students, research organisations, law enforcement agencies that need to train sniffer dogs, and similar professional clients. This business, JonsBones, is legally entirely separate from the museum he later created.

Ferry found that there was a significant supply of bones from sources that are totally above board. E.g., he buys specimens that are passed down from doctors, medical professionals, and individual sellers. Oftentimes, heirs even throw them into the bin. Ferry's approach is to use his business to get these bones back into the medical field for the purpose of education. He cites a UK study which stated that since the implementation of teaching using plastic skeletons, there has been a 50% increase in medical students needing to retake their entrance exams due to inadequate anatomical knowledge. In the same vain, there have been reports of a several-times increase in malpractice lawsuits due to inadequate anatomical understanding. India changed its regulation of the industry in 1985, which effectively killed new supply from this country. By feeding old medical bones back into the system for educational purposes, Ferry provides an ethical, common-sense solution to a difficult, widespread problem.

Using his personal collection of bones and given his strong desire to educate the public about this field, Ferry eventually launched The Bone Museum. He now runs the museum, an educational operation, and a mail-order business – all before reaching the age of 25.

Source: JonsBones, online shop (skulls section).

Possibly most importantly, Ferry has given osteology and the collecting of human bones a younger face and a fresh vibe overall.

His museum is located in a loft building in Brooklyn's trendy Bushwick area, and Ferry's looks and personality made him become a skull-ebrity. The media love him, and he has been featured the world over by now. More PR is guaranteed given Ferry's ongoing, careful effort to navigate the sensitive subject of "bone politics" (there is such a thing), and it'll be mostly positive.

A visit to his museum is highly recommended if you ever find yourself in New York.

I had long had the idea for this article, but it was only after a brief conversation with Ferry that I located the two books which are the single best contemporary resource for anyone who wants to get a feel for the potential future of human bones as more than just a collectible. There is a serious alternative investment waiting to be discovered by the investment community.

The sector's iconoclasts – and the issue of provenance

Outside of the realm of museums large and small, there has long been a small but seemingly thriving sector of collectors and enthusiasts who collect human bones and other forms of human remains.

For anyone who wants to get a closer handle on who is currently part of that scene and what they have been collecting, "Morbid Curiosities" by Paul Gambino is a must-read.

The book contains 17 profiles of collectors, each outlining what drew them to the field, what they have been collecting, how they are going about their hobby, and what type of bone or specimen they are dying to own (again, forgive the cheap pun). Some are enthusiasts who are just starting out, others have been in this field for decades and may even have turned it into a business.

From the same realm is "Skulls: Portraits of the Dead and the Stories They Tell", by the same author. As the title indicates, its focus is narrower. It's worth noting (even though it's not surprising) that a large part of the interest in human bones is directed towards the skull. The skull is home to four of our five senses, encases the brain, and boasts the most expressive set of muscles in the human body. It's a little known fact that no two skulls are ever alike, i.e. they are as distinguished from each other as our fingerprints. The fascination with the skull existed during the days of Western colonialists collecting shrunken skulls, and it remains true in an age where scientists promise the wealthy that our heads may one day live on without our bodies. For yet more reading on why the skull is such a focal point, I recommend "Severed: A History of Heads Lost and Heads Found", published in 2014 by Frances Larson.

Photo courtesy of JonsBones.

As Gambino's work on skulls shows, those 3,000-year-old elongated skulls from South America seem to feature on the wish list of collectors more often than any other type of specimen. Did that Indiana Jones movie have an effect?

Indeed, human bones are all the more valuable if they have an added edge. Most often, that would be the history of the person they once belonged to. Human remains are usually treated differently if they can be named, or if there is a link to the present.

Being able to ascribe a bone to one – and really, just ONE – individual adds to their allure. Unlike paintings or manuscripts, which can be duplicated or mass-produced, a person's items like bones, teeth, or locks of hair are unique and finite. They provide an intimate glimpse into the life of an individual who shaped the course of human history.

Such items do pop up in public, even today. E.g., in 2023, the BBC's "Antiques Roadshow" saw a guest bring in a few strands of hair that once belonged to the late poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Wordsworth, and Robert Southey. The owners were astounded to learn that the hair would be worth GBP 30,000-40,000 if sold.

Source: Daily Mail, 12 June 2023.

Another famous example includes a tooth of Sir Isaac Newton which was turned into a decorative ring. Last sold in 1816, it'd fetch a fortune if it ever came up for auction again.

Source: Reddit.

Now imagine the bones of a person who was prominent not just in their native country but globally.

There is such a thing as "celebrity bones". Museums have long experienced that some bones attract 10-100x the level of interest than other exhibits. Obvious winners are skeletons of people who suffered from dwarfism or gigantism. The gigantism skeleton shown at The Bone Museum is one of only three that are on public display worldwide; you can imagine how many visitors take selfies!

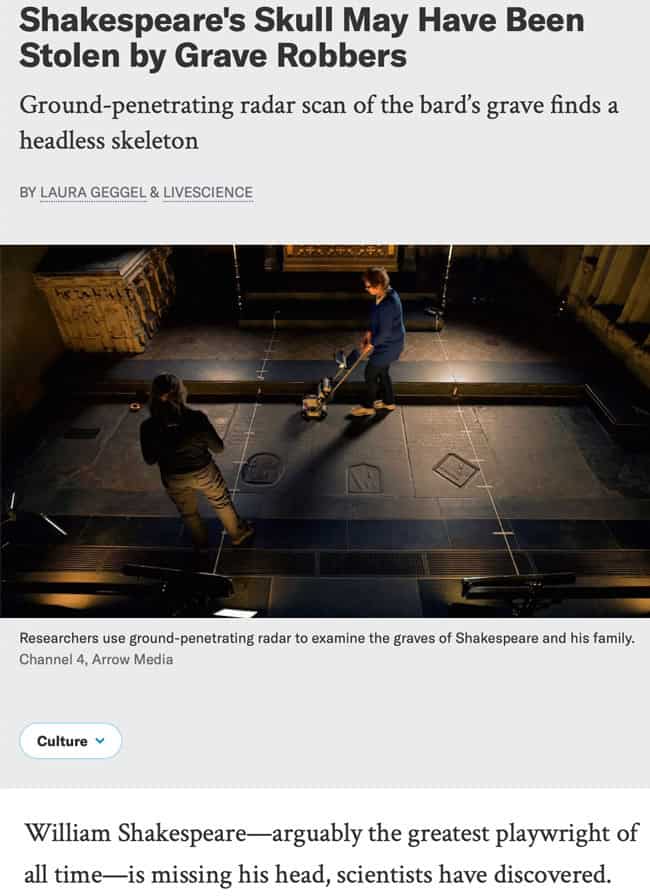

That's before we speak of bones from REALLY famous people. E.g., William Shakespeare's skull may be out there somewhere – though its provenance would be a problem as it was most likely stolen from his grave!

Source: Scientific American, 31 March 2016.

Indeed, Mike Zohn of Obscura Antiques & Oddities in New York City reportedly sometimes has people try to sell him skulls with obvious burial signs. Graverobbing – which is illegal, of course – may still be a thing nowadays, at least on the odd occasion. Serious collectors, though, would all stay well clear of anything that is of dubious or even unclear provenance.

The odd bit of mischief that has taken place in this sector probably only adds to its intrigue, and it makes those specimens that have impeccable provenance all the more desirable and valuable.

In any case, there is no lack of public interest, even now. E.g., one prominent collector of human skulls, Ryan Matthew Cohn from upstate New York, even got to co-host a show "Oddities" on the Science Channel.

That's before we even mention the "Body Worlds" exhibition. While not exhibiting bones, its plastinated, dissected human bodies are in the same realm as bones. With over 50m visitors so far, Body Worlds claims to be the world's most successful touring attraction.

Who will create a similar touring exhibition that combines the fascination of human bones with the odd celebrity bone? The world is fascinated by celebrities, and there is already the term "deleb", which is industry lingo for "dead celebrities". An opportunity seems to await, which could prove a catalyst for the valuation of rare, special human bones.

Maybe the success of The Bone Museum and its social media is an early indicator of what's to come.

Could this ever become a sector that is large enough for serious alternative investors to deploy significant sums of money?

You'll be surprised!

The size of the market

Analysing the potential size of this market isn't entirely straightforward, but if you know where to look, there is enough data to indicate that it could become a market measured in the double-digit billions.

For much of the 20th century, India was the largest supplier of human bones to the rest of the world. A number of factors specific to India enabled this industry, e.g. the large population number combined with the caste system meant that a significant number of corpses was always available. The country had also built had a significant body of expertise in preparing bones and skeletons, which no one country ever managed to match.

According to scientific literature, between 1947-1985, an estimated 2.4m skulls and skeletons will have been exported out of the city of Kolkata alone.

Currently, the average price for a human skull is around USD 2,600, while a complete skeleton averages USD 8,500. If you assume a midpoint of USD 5,000, the estimated market value of skeletons and skulls exported from Kolkata alone would run to about USD 12bn.

Of course, not all of these bones will still be around. However, the calculation does not include bones from other Indian cities, or from other countries that at some point had a history of exporting human bones. This list would include China, Russia, Australia, the United Kingdom, Germany, and France – all countries that had a bone-exporting industry at some point, although none ever managed to match what India had built until it closed down the industry in the mid-1980s following a scandal.

How many of these bones will have gone to countries where they can be expected to still exist and be available for purchase?

The US provides an interesting reference point. Between 1920-1980, 500,000-600,000 medical students graduated in the US. Given they all had to acquire their own bones, it implies at least 600,000 skeletons were imported into the US solely for medical students. This doesn't account for additional purchases by universities, individual skull acquisitions for anatomy classes, doctors' offices, research facilities, museums, or other applications requiring full medical skulls. All taken together, the US is probably home to anywhere from 500,000-2m sets of bones and skeletons.

Source: The Bone Museum (photo by Swen Lorenz).

Many of the doctors who graduated during this period are either approaching retirement or have already retired and will pass away over the next decade or two. Their heirs will have to deal with the skeleton(s) in their closet. This could make for supply that weighs on prices, or for an opportunity to acquire significant numbers of bones and build larger, well-funded collections with the wherewithal to thrust this sector into a new era.

We'll get back to that…

Let's first look at price trends and valuations.

Price trends over the last 100, 40 and 5 years

Much as there is no one-size-fits-all valuation formula for human bones, reliable data points exist.

E.g., in the 1920s, sets consisting of a half-skeleton retailed for USD 15-30. We know as much because some of these boxes still exist today, including their original purchase receipt. These boxes today are selling for USD 7,000-9,000. Over the last 100 years, they appreciated by 6.5% p.a.

Source: The Bone Museum (photo by Swen Lorenz).

Reliable data also exists on child skeletons. They are very rare to come onto the market, which is why they cause a fair bit of attention when they do. In 1984, such a skeleton would have fetched about USD 350. Today, it will likely sell for USD 25,000 – an annual appreciation of 11.5%. During the same period, the S&P 500 will have only yielded 8.7%.

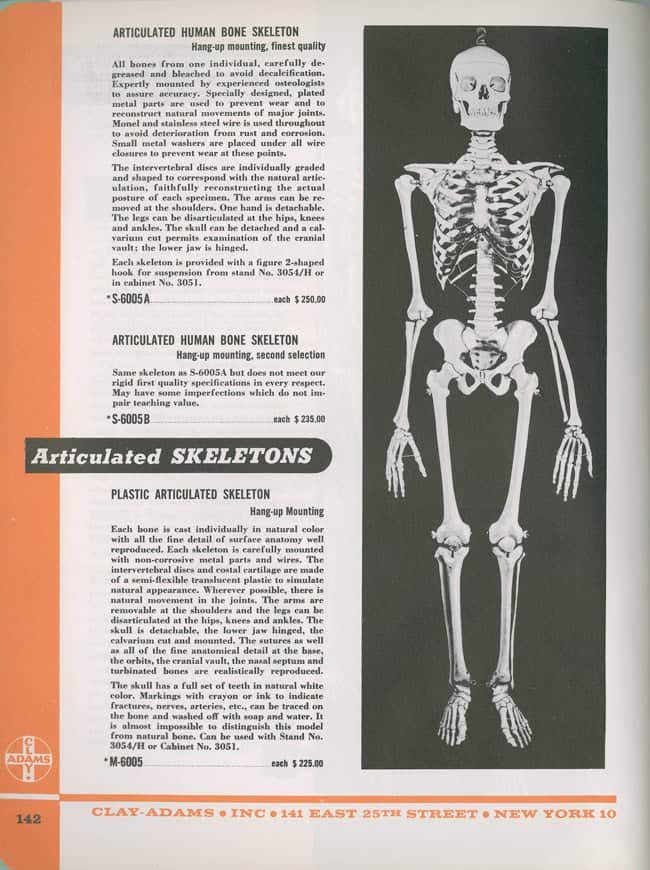

Source: Clay Adams catalogue, New York (1935).

Where will prices go from here?

While prices for human bones have risen several-fold over the last five years alone, they seem to remain comparatively low in absolute terms.

Skulls are the perfect example. Skulls are the most desirable part of the human skeleton, but even now only truly rare, unique specimens reach into the mid-five figures. For the most part, you can buy outstanding specimens for USD 10,000-25,000. I had a comparable "this seems really cheap" gut feeling when, in 2001, I tasted a 1926 bottle of Macallan whisky. It was GBP 8,000 for a bottle then, and it has since brought USD 2.7m at auctions.

This may be an extreme example, but it illustrates a point.

E.g., child skeletons are extremely rare. So rare, in fact, that there is only one known case of a child skeleton coming onto the market in the last ten years. Still, this would likely fetch only USD 25,000. Measured against prices paid for other objects and given its extreme rarity, this does not seem like an ambitious price.

These are all individual data points, but they provide a feeling where this market is at right now.

What's relatively easy and clear to determine are the factors that will likely be key determinants in the pricing of this market.

Success factors – and hurdles

To be clear, the very notion of looking at rare, special human bones from an investment perspective will upset some. Naturally, attributing a monetary value to human remains is both a complex and delicate matter.

Unlike art or any other form of alternative investment, these objects will never be merely commodities. They were once part of living human beings, and as such they have to be treated with the utmost respect and dignity. Anyone who takes an interest in the potential investment angle of this field will always have to keep in mind that these objects hold profound historical, scientific, and educational significance. Investing into such objects will carry certain obligations, such as the need for storage that is not just geared towards preserving the object but also aligned with the special factors mentioned above.

Still, over the past three decades, a range of alternative investments have risen from obscurity to high-priced asset. My hunch is that the following factors will work towards human bones becoming something that not just collectors but investors take an interest in.

Opacity: despite spending a few hundred dollars on subject-related books and reading voraciously online, it feels like I have only scratched that proverbial surface. In opacity lies opportunity, because a lack of transparency prevents efficient pricing.

Large audience: the success of The Bone Museum leaves no doubt that there is a huge potential audience for this subject.

Generational change: osteology and related aspects used to be in the hands of an older generation, but Ferry's success is an indicator that a generational handover is afoot.

Large collections: in "Morbid Curiosities", I read of one collector who buys entire collections at discounts. He sells off individual items and then owns the remainder effectively for free. This strikes me as a value situation, similar to buying a company at less than the sum-of-the-parts. The bid/ask spreads in this market will large be huge, and possibly 2-4x the price.

Decreasing competition (of sorts): if large museums retreat from this field, there'll be less competition over audience attention and a bigger opening for newcomers to enter.

Rarity: without a shadow of a doubt, many rare specimens exist in this market which will make for public fascination, ongoing media interest, and other value-enhancing factors. Also, with students increasingly learning on the back of digital models or 3-D printed replicas, and regulation only getting more stringent, the supply of these objects will likely decrease.

Bad marketing: similar to Scotch whisky in the early 2000s, the idea of collecting (or investing in) human bones seems badly marketed but with a lot of room for rapid improvements.

Sufficient scale: surprisingly, there is no lack of scale for niche funds to get involved. Someone who wanted to deploy USD 10-30m could do so, and possibly even buy out entire collections. Deploying USD 100m would be more complex and require some time, but even this appears feasible if someone wanted to facilitate the entire market reorganising around one large pool of liquidity – and possibly help a museum (or two) get rid of its entire collection.

Changing attitudes: the response to death and dying is changing in many societies, as witnessed by the increasing acceptance of assisted suicide and the growing demand for funerals that celebrate the deceased's life. (For an excellent overview of how the response to death has changed over the past millennium, check out Philippe Aries' 600-page tome "The Hour of Our Death".)

These are major factors evolving in favour of this market.

There are major problems, too.

Significant complexity: the opacity is both a benefit and a hindrance. E.g., shipping items comes with considerable complexity, because of differing national regulations and policies of courier companies. An investor would probably want to focus on just one jurisdiction, which would most likely be the US.

Fraud: like the arts market, there is a significant risk of falling for fraudulent specimens. There is an easy test – just push a hot needle into a bone, and if it smells like burned hair (rather than burned plastic) then it's real! However, fraud can also come in the form of faking an item's provenance, which may be the bigger problem overall.

Other factors are both a hurdle and an opportunity:

Supply overhang: at least for now, a massive amount of supply is coming down the pipeline. Heirs selling individual bones, some collections being tentatively for sale – it may well be that these factors will weigh on prices. They could also do the opposite, though. A single large investment entity could use this as an opportunity to get to scale and create a modern, attractive market for human bones, e.g. by backing a new, bigger museum. This could be the accelerant for the market to truly come onto its own.

Source: JonsBones, 10 February 2021.

Having looked into all this, I believe that before too long, *someone* will eventually set up an investment entity for human bones. The first person to do so will be guaranteed global interest by the mainstream media – which may be another reason why someone will do it.

For a well-funded, well-managed investment entity, there'd be manifold opportunities to increase the value of a collection and generate income, such as selling replica of high-profile items, and creating other forms of swag based around celebrity specimens (never mind selling tickets for a wandering exhibition).

Such an entity would have to develop its own model for sourcing specimens and marketing them. It would also need a framework for handling what will always be a slightly more complicated and delicate public perception and legal situation. By doing so, it could help to launch this sector as an investible asset class.

At the heart of such an entity would probably have to be a buy – develop – sell model. Just as Ken Griffin has shown, there could eventually be UHNWIs who want to have the ultimate conversation starter in their study. Such collectors could provide the eventual exit for the investment, once the market is more established.

Such an entity would also have an opportunity to fund expeditions to find long-lost celebrity bones:

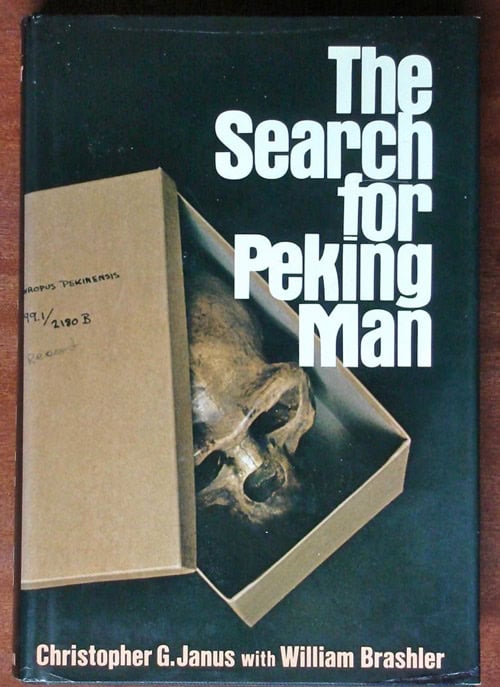

- If someone made a serious effort to find the long-lost skeletons of the original "Peking Man", a global media frenzy would be guaranteed. These are the bones of a series of individuals who were discovered at the site of Zhoukoudian, just outside Beijing (then: Peking) in the 1920s and early 1930s. They vanished while in transport to the US in the run-up to Japan's invasion of China, and their whereabouts have been clouded in mystery ever since. Finding Peking Man would be the modern-day equivalent of finding Tutankhamun's tomb.

1975 book about one of archaeology's greatest unsolved mysteries.

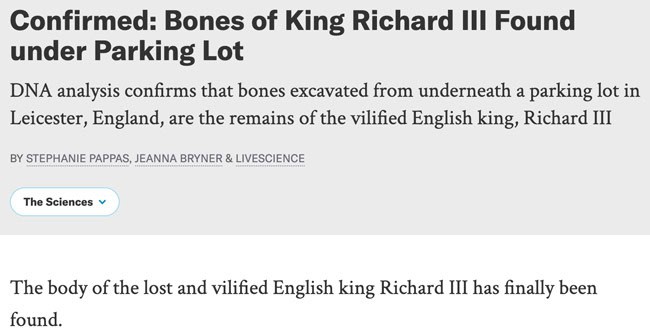

- Britain offers manifold opportunities to look for the bones of kings and other important historical figures. In 2013, a team of archaeologists found the remains of Richard III under a parking lot in Leicester. As The Times reported on 25 August 2023, "the bones of great monarchs have, over the centuries, been moved, sold, hidden, destroyed or simply lost". That sounds like there are other opportunities for similar finds, and academics usually lack funding to go on organised expeditions.

Source: Scientific American, 4 February 2013.

- That mystery of Shakespeare's skull is also still unsolved. How much could you charge for an exhibition where visitors could see the skull from which many of the world's greatest classics came? How much would a (less timid) museum in the Middle East pay for such a crowd-puller?

The discovery and acquisition of celebrity bones can also be quite simple, though. At times, these specimens turn up in a box in someone's cellar or attic – cue the recent discovery of the skulls of ten soldiers killed at the infamous battle of Waterloo. An elderly woman had even kept some these bones on her mantlepiece for years, talking to them and coming to think of them as a "friend". See the following article.

Source: The Telegraph, 25 January 2023.

In any case, given where this market is at, there will be many low-hanging fruit for individual collectors and investors.

Where is that individual who wants to delve into the netherworld and make such an investment entity happen?

It all reeks of an opportunity for investors to hunt for undervalued specimens and put them away for the next 10-20 years.

I did want to get a second opinion, though.

How does someone on the inside view recent trends in this sector and the longer-term investment prospects of carefully selected human bones?

I contacted Ferry, who shared his insights and advice with me:

"The lack of federal regulations in the United States – apart from varying state-by-state laws – has fostered a secondary market where human osteology is bought and sold. This market is driven by factors such as scarcity, demand, public perception, and the supply of these pieces. These dynamics have led to a significant increase in monetary value over the past several years. When I first purchased my human skull I used to buy them for $150 to $300. The same skulls today is selling for between $2500-$4000. There are some medically prepared skulls that can fetch upwards of $50,000 if rare enough. Between 2018-2024, most human skulls appreciated by approximately 60% annually.

The ethical implications of this market cannot be overstated. The key factor is that specifically these pieces from the medical bone trade not produced anymore with India's 1985 ban subsequently ending the bone trade as we know it. The majority of sales have moved into the secondary market. This means that in terms of scarcity and demand – which is the quintessential element of any monetary value – these pieces are inherently not being produced anymore. Thus, they're only going to get rarer as the years continue.

From an investment standpoint, human remains present inherent risks, including the potential for new laws and regulations that may restrict or ban their sale, as seen in states like Minnesota. The volatility of this asset class, combined with the public's growing awareness of sourcing practices, introduces uncertainty into any discussion of monetary appreciation.

In determining the monetary value of human remains, four primary factors typically influence pricing:

- Provenance – The history or origin of the piece, such as its previous ownership or association with renowned collections.

- Quality – The condition of the specimen, as damage or missing elements (e.g., teeth) can significantly reduce value.

- Pathology – Unique or rare conditions, which may enhance a piece's scientific and educational importance.

- Preparation – The method and craftsmanship involved in preparing the specimen, which can vary widely in rarity and quality.

While these factors provide a framework for understanding the market dynamics, it is crucial to reiterate that human remains should never be reduced to mere monetary value or treated solely as investment opportunities. At The Bone Museum, we focus on their educational, historical, and cultural significance, using these pieces to foster understanding and respect for the human condition."

How to get in on the act while the market is where it's at now?

Further resources for the early-bird investor

For my article, I scooped up just about any book available about the sector.

Besides the two titles mentioned above, there is "Skulls and Skeletons" from Christine Quigley. The 2001 book is the ideal starting point for anyone who wants to engage in serious research and educate themselves about technical aspects.

For any individual trying to get a foot in (or someone's foot out – puns, puns, and more puns!) and buy their first skull, there are many ways to do so through reputable dealers:

- Skulls Unlimited (Oklahoma)

- The Bone Room (California)

- Bauer Handels GmbH (Germany and Switzerland)

- The Copper Hammer (Florida)

- 6 Brains (UK)

Besides, there are Instagram accounts such as:

- Skullture Factory (a self-described headhunter)

- Skullessence (tribal skulls)

- Craniac (also tribal skulls – they are forever popular!)

It's a vast area to delve into – and much bigger than what I had expected to find.

Whether it appeals to someone will be more divisive a question than investing into vintage cars, fine wine, or rare handbags.

In any case, it's an asset that is currently underappreciated and underdeveloped, but which could offer non-correlated, significant upside.

After all, most trends and fashions return eventually.

The second half of the 19th century had seen the proverbial "craze" for this sector. It's been a while – so maybe a return of the craze is overdue already?

Podcast: The Value Perspective with Swen Lorenz

What's Weird Shit Investing all about?

On The Value Perspective podcast, the Value Team at Schroders and I take a closer look at this conference, which had its inaugural edition in 2024. How did it come about, and what's in store for 2025?

We also reflect on the concept behind Undervalued-Shares.com, and what makes it stand out from other investment blogs.

Podcast: The Value Perspective with Swen Lorenz

What's Weird Shit Investing all about?

On The Value Perspective podcast, the Value Team at Schroders and I take a closer look at this conference, which had its inaugural edition in 2024. How did it come about, and what's in store for 2025?

We also reflect on the concept behind Undervalued-Shares.com, and what makes it stand out from other investment blogs.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post: