Image by Simon Vayro / Shutterstock.com

Financial markets are entering a new era, and many investors are looking for entirely new investment ideas.

For 29 years, I have been following developments at Lloyd's of London, the famous insurance market in the City of London. Much as I have never written about it previously, I always knew that one day, it'd be the right moment to introduce it to my readership.

At a recent dinner with readers in London, I launched a teaser of the subject. Or, to be more precise, I introduced a reader who is what I like to call a "hidden genius". He has never previously appeared in public, but he has an encyclopaedic knowledge of this market – and a proven track record of investing in it.

When my reader explained his view of Lloyd's of London, the entire table listened intently. Had it not been for the noise in the rest of the restaurant, you could have heard a pin drop.

That moment, I knew the time had finally come to write about the subject.

Investing in Lloyd's of London is an investment theme that is complex, intransparent and possibly even unfair – and all the more interesting for that reason!

The near-demise of Lloyd's

Ask just about anyone about "Lloyd's", and they'll probably mention two words:

- "Names"

- "Asbestos"

The terms relate to two events that unfolded mostly in the 1980s and 1990s, but which still dominate the perception of Lloyd's in the minds of many.

Lloyd's is a market for insurance and reinsurance contracts. Crucially, it is not an insurance company itself, but a marketplace only. Clients can use Lloyd's to meet underwriters, or "members", and negotiate insurance contracts.

The Lloyd's market started in a coffee house run by Edward Lloyd in 1688, mostly focussing on marine insurance at the time. Since 1986, it operates in the iconic Lloyd's building in Lime Street in the City of London. One of the market's peculiarities is that even 334 years later, most of the business is negotiated in person.

The Lloyd's building in London (image credit: eric laudonien / Shutterstock.com).

In the olden days, Lloyd's operated like a gentlemen's club. At its peak, it had 34,000 members, or so-called "Names". The Names put their entire personal fortune forward as collateral for insurance contracts. For many decades, it's been a way for English aristocrats and other well-to-do individuals to generate an additional return out of their assets. E.g., they could pledge an equity portfolio or rental properties as collateral. Provided their insurance contracts didn't suffer a loss overall, they could keep capital gains, dividends and rental income from their assets AND pocket a profit from the insurance contracts they backed with their fortune.

Obviously, when the insurance contracts incurred a loss, they had to dip into their personal pockets and cover the loss – if necessary, their liability extended "down to their cufflinks", as people used to say at the time. On balance, though, for many years it's been extremely lucrative to be a member of Lloyd's. As one masters thesis on the Lloyd's insurance market concluded: "in the 50s, 60s and 70s, the market's individual investors – called Names – enjoyed fabulous rewards".

It all came to a grinding halt in the 1980s, and that's what had been haunting the market's reputation until recently. Back then, the world started to catch on to the health dangers from asbestos, and legal claims in the US brought unexpectedly high punitive damages from asbestos-related health claims. Many of the Names had unlimited liability for insurance contracts dating back to the 1940s-1970s. Thousands of Names lost their entire fortune, several suicides followed, and the Lloyd's market nearly collapsed.

Many of the Names affected were household names or celebrities, which was one of the reasons why the affair turned into one of the most widely reported financial disasters of all time.

For anyone wanting to delve deeper, worthwhile books include:

- "Ultimate Risk: The Inside Story of the Lloyd's Catastrophe", by Adam Raphael

- "For Whom the Bell Tolls: The Lessons of Lloyd's of London", by Jonathan Mantle

- "On the Brink: How a Crisis Transformed Lloyd's of London", by Andrew Duguid

In 1995, all pre-1993 liabilities (except life insurance) were placed in a special purpose vehicle, Equitas. The spin-off was fraught with complexity and controversy, but it saved the market from going under altogether. In 2009, the affected Names were finally freed of all remaining legal liabilities. Three years prior, the remaining portfolio of Equitas had ended up in the lap of Berkshire Hathaway (ISIN US0846701086, NYSE:BRK), who had spotted an opportunity to extract value from the legacy portfolio.

It has been 27 years since the crisis got resolved, but many people still primarily associate these events with Lloyd's. Except, of course, those who are too young to have been around at the time, which is now almost anyone under the age of 45. With a new generation rising through the ranks, Lloyd's has an opportunity to start with a clean slate. Its reputation could be transformed over the coming years.

That's where the opportunity lies. There is a perception gap, and most people being hopelessly behind with their assessment of Lloyd's opens up several possibilities for benefitting financially.

Specialised knowledge required

The inner workings of the Lloyd's insurance market are quite difficult to understand.

A search on popular book websites for books that explain Lloyd's in a non-academic way will likely get you rather dated results:

- "An Introduction to Lloyd's Market Procedures and Practices", 1987

- "Lloyd's of London: An Illustrated History", 1987

- "Lloyd's of London: A portrait", 1984

Outside of describing the near-demise of the institution, book authors have had fairly limited interest of late in explaining to the public how the Lloyd's insurance market works.

Much has changed since the mass-bankruptcy of Names – but some things haven't changed at all. E.g., much of the business written at Lloyd's is still conducted face-to-face in the world-famous Underwriting Room, which has nearly 5,000 people working there.

The Lloyd's marketplace in Lime Street.

Today, Lloyd's is the place where 5% of the world's insurance business is written. Maritime insurance remains a core area of the market, as do esoteric risks, such as insurances for footballers' legs or actresses' bottoms. Members of Lloyd's are often at the forefront of insurance innovation. This was true in 1904, when Lloyd's offered the first-ever auto insurance, and it's true today with new insurance products aimed at cyber risks.

What has changed is the role of individuals, i.e. the Names. After peaking at 34,000 Names in the 1980s, Lloyd's today has just 2,000 Names. Collectively, they make up just 9% of the insurance writing done at Lloyd's.

The vast majority of insurance business at Lloyd's is written by syndicates that are organised as limited companies or operate as some form of specialised legal entity. The era of individuals playing a large role at Lloyd's as underwriters is drawing to a close, which is also driven by the immense complexity of today's insurance market. Operating as an underwriter at Lloyd's requires an aptitude for grasping a multitude of acronyms and for convoluted reporting. Lloyd's truly is for the experienced investor only, and that puts individuals off from getting involved.

Those who do make the effort to dig deeper find many unusual and interesting aspects. E.g., anyone wanting to deploy money through Lloyd's will want to have their underwriting handled by the more successful syndicates. However, syndicates have limited capacity to take outside money onboard. The right to participate in a specific syndicate can in itself be a property right, and may even be traded like a security. Outside of making money from underwriting insurance contracts, you could also generate profits by buying and selling so-called "capacity", i.e. the right to deploy money through specific syndicates.

This is just one example of the many different angles that exist to play this market.

Regular Weekly Dispatches readers will sense where this is going. Lloyd's is a market that is complex, has been largely outside of the public eye for decades, and offers those with access to superior information an opportunity to gain an edge. There are bound to be underexploited opportunities for those who know where to look.

Could a private investor possibly participate in this market, and maybe even have an edge over other investors?

This is probably less far-fetched than you'd think, thanks to the plethora of financial instruments that you can find on public markets.

An easy way to get Lloyd's exposure (on the cheap)

As with almost any theme, there are publicly listed securities and instruments that give you exposure but which also allow you to liquidate your investment on a daily basis.

In the case of Lloyd's, the easiest possibility for private investors to get exposure is by buying stock in one of the publicly listed insurance companies that operate Lloyd's syndicates.

One of them is Beazley plc (ISIN GB00BYQ0JC66, LSE:BEZ), a holding company that manages no less than six Lloyd's syndicates, all of which have top ratings.

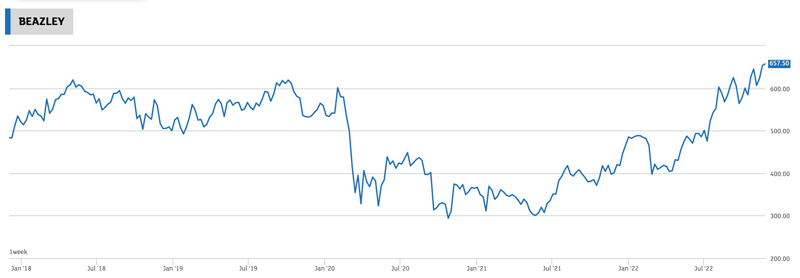

While stock markets were mostly heading south this year, the stock of Beazley gradually moved north. It's up 66% this year and currently trades at an all-time high.

Beazley plc.

Even an unexpected equity placing couldn't halt the stock's rise this year. On 15 November 2022, Beazley announced its intention to increase its share capital by 9.99% to raise an additional GBP 382m (USD 450m) in equity. This caught the market by surprise and could have easily been perceived the wrong way, but the stock has only risen further since.

Anyone in need of a new insurance contract recently will be aware of just how steeply premiums have risen.

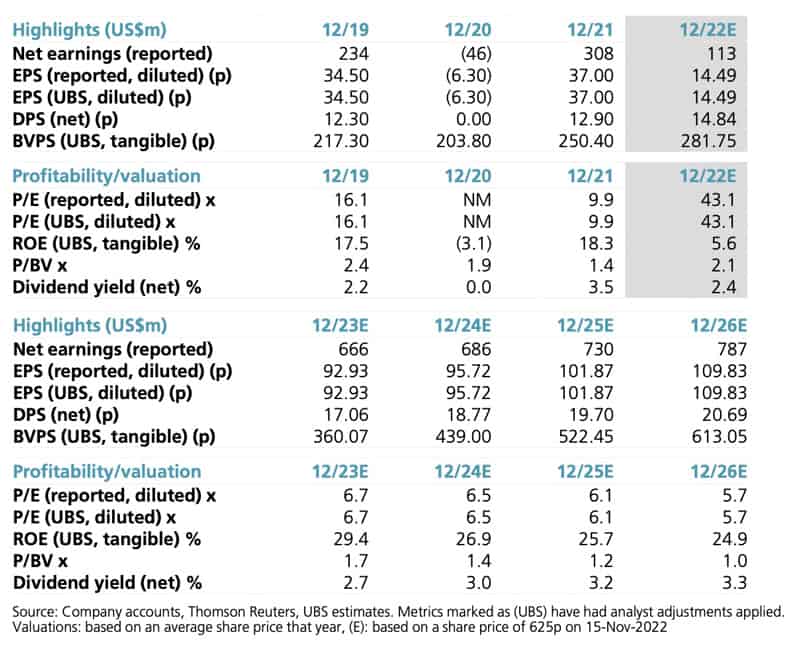

Beazley does not work exclusively on the Lloyd's market, but it's one of the stocks widely associated with it, and it has a reputation for being a smart operator of Lloyd's syndicates. The stock is currently trading at a forward price/earnings ratio of 6-7 (see table below). The placement of shares was all but dealt with in 24h, and the company now has additional firepower for growing it business.

Source: UBS, 15 November 2022.

Growth – and profitable growth, for that matter – is what Lloyd's may increasingly get a reputation for. Nearly three decades after its near-death experience, we may finally see the early phase of the insurance market shedding its image and experiencing a renaissance.

An exciting new era

Today, Lloyd's isn't just largely free of legacy risks, but it's also double-protected against major new issues. For example, as a safety measure to prevent another near-meltdown, Lloyd's has stashed away GBP 3bn in its "Central Fund", a ring-fenced entity that serves as a backstop. It can be called on in the event that a claim against any Lloyd's member blows through its own capital buffer.

Interestingly, since June 2021, the Central Fund has in turn its own insurance against crippling losses. Lloyd's has agreed a GBP 650m cover to shield the fund's reserves. That's a safety mechanism protected by another safety mechanism. This reinsurance of the reserve fund was created by J.P. Morgan, who in turn used it to create an innovative financial instrument that they placed with their clients.

Lloyd's should now be able to focus on what its executive had already outlined as a vision in 2019. Back then, Chief Executive John Neal told the Financial Times: "'Today, Lloyd's is 5% of the world flow for corporate and speciality insurance. There's no reason why we can't be 10% of the world's flow."

The pandemic slowed down the growth ambitions, but Lloyd's has recently come back with a striking announcement.

In August 2022, Neal informed the Financial Times that it was on "the hunt for billions in fresh capital" and going to launch a "drive to bring in money from outside investors". Specifically, Lloyd's wanted to open itself up to a wider array of investment funds. Its management team believes that it could attract billions of alternative investment capital and "boost its competitiveness with other hubs such as Bermuda in the growing market for insurance-linked securities."

Neal's plan is nothing less than to turn Lloyd's into "the most advanced insurance marketplace in the world". To this end, he had published a 146-page document in 2019, entitled "Blueprint One". There is now an updated version, "Blueprint Two", which even has its own website.

The wider public has limited awareness of these changes. The Financial Times does stellar reporting about Lloyd's (and it is widely read), but other information resources are scarce. Lloyd's YouTube channel has a paltry 4,000 subscribers, and a recent promotional video of Blueprint Two had just 395 views when I wrote this article. For a company that controls 5% of the world's insurance markets, there is a surprisingly limited level of awareness of the bigger picture.

This is likely to change, though.

In summer 2022, I had a chance to get an inside tour of Lloyd's with one of the market's members. It was palpable that a new era is afoot.

Yours truly inside Lloyd's of London (permitted with a guide or member only).

There are multiple opportunities that I have identified as worth taking a closer look at:

- Publicly listed companies with Lloyd's exposure.

- Opportunities to exploit the intransparency and complexity of the market (I am keeping this vague on purpose as I don't want to give away good ideas).

- Possibilities for new – or at least innovative – financial products using the ongoing changes of the market itself, similar to what J.P. Morgan recently did.

As you can gather from this Weekly Dispatch, I have already done a fair bit of work. Some aspects of today's article were a slight simplification of the subject matter, for the purpose of readability. Following this primer and introduction, Undervalued-Shares.com Members will read about Lloyd's again in the future.

Watch this space!

Latest stock pick out now

When someone on the inside of a company is keen to buy every single share that they can possibly get hold of, it's usually a sign that you should pay attention.

That's the situation right now at Atari SA, the Euronext/Paris listed company that owns one of the most iconic and – potentially – most valuable brands of the early days of computing and gaming.

Its major shareholder has been buying additional stock hand over fist. Ignore his fast movements at your peril...

Latest stock pick out now

When someone on the inside of a company is keen to buy every single share that they can possibly get hold of, it's usually a sign that you should pay attention.

That's the situation right now at Atari SA, the Euronext/Paris listed company that owns one of the most iconic and – potentially – most valuable brands of the early days of computing and gaming.

Its major shareholder has been buying additional stock hand over fist. Ignore his fast movements at your peril...

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post: