Gold stocks remain undervalued, with considerable upside potential. I picked the brain of Dominic Frisby, who has just released a new book on gold, to get his take.

Pearson – turning a lumbering textbook giant into a digital racehorse

I much admire activist investors, though I also feel sorry for them.

Being an activist is far more difficult (and less glamourous) than it appears to be. You can make quite a splash by revealing a significant stake and going public with your demands. Initially, that then often leads to a wave of speculation and the stock price going just the way you wanted.

However, enacting lasting, successful change at a company is usually a matter of at least two to three years. Unexpected roadblocks turn up. Economic and financial events affecting the rest of the world can mess up the best-laid plans. Usually, badly-run companies reveal nasty surprises once someone starts digging around.

Whenever I see a stock rally because an activist has turned up, I make a mental note to revisit the entire situation about half a year later. Usually, things have calmed down by then and the stock is worth a closer look.

Back in June 2020, my ears perked up when Cevian Capital, a Swedish activist investor, disclosed a 5.4% stake in Pearson (ISIN GB0006776081), the GBP 4bn market cap education and publishing group listed on the London Stock Exchange. Cevian had previously run campaigns at ThyssenKrupp and Nordea, and it is said to be Europe’s largest activist investor (although they would rather describe themselves as “engaged investor”). Cevian manages around EUR 12bn, and one of its funds once trebled its investment when it successfully “engaged” Danske Bank (ISIN DK0010274414).

Is Pearson going to be a similar success?

The market did take an initial liking of the situation.

Between mid-May and late June 2020, the stock climbed from GBp 420 to GBp 580. On the day of the Cevian announcement alone, it jumped by 11%. In August 2020, it reached GBp 640. While markets were generally favourable at the time, it’s clear that investors considered Cevian a long-term positive for Pearson.

However, the stock price has since come back down – slightly below GBp 500 as I wrote this article. That would be about the same price that Cevian paid, if not even a smidgen lower.

As ever so often, following an initial bout of enthusiasm, it turns out that things will take longer than expected and be just a bit more difficult, too.

Is now a good time to follow in Cevian’s footsteps and load up on Pearson stock?

I set out to investigate.

A decade-long structural decline

Pearson, in case you didn’t know, used to be a publishing empire with far-flung activities and high-profile assets.

Its primary business had long been textbooks for students, with a strong focus on the US market. Until the late 1990s, pushing overpriced textbooks towards students was the proverbial license to print money. Many of these books were quasi-monopolies; students had no choice but to buy them. The cash flow reaped in the textbook division enabled Pearson to go on an acquisition spree.

That was then. The world has changed.

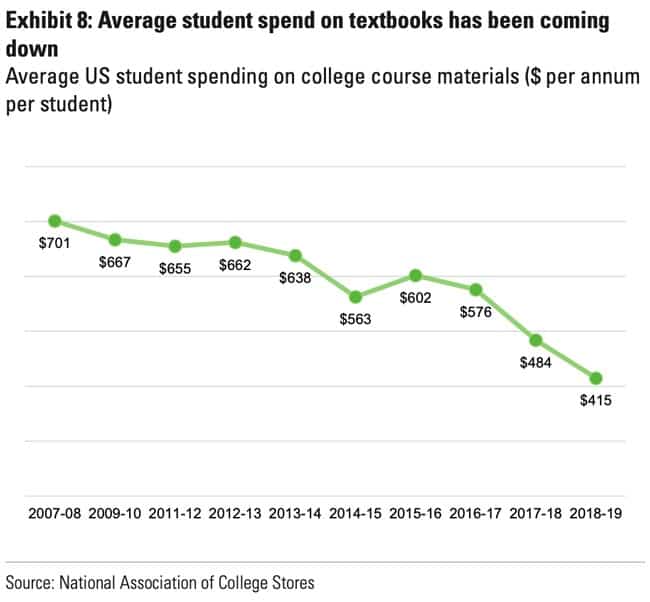

During the entire 2010s, the textbook business has suffered from a gradual decline. Students switched to renting rather than buying books, buying used copies over the Internet, and using web resources. Between 2007/8 and 2018/9, the average spend on student materials fell by 40%. Falling enrolment numbers added further pressure on the business.

As a result, between 2015 and 2019 alone, the textbook division’s revenue fell from GBP 1.6bn to GBP 1.1bn.

It’s been evident for nearly a decade that Pearson was fighting an uphill battle. At the beginning of the decade, the stock was trading above GBp 1,000. Whereas global markets rallied throughout the decade, Pearson halved in value.

During that period, the company enacted ongoing cost savings programmes, and it simplified its portfolio. It sold off the Financial Times, The Economist, Penguin Random House, and Wall Street English – all fairly major brand names.

Selling the family silver provided temporary relief and filled the coffers, but it didn’t convince the markets that the remaining business of Pearson was on a good path. Market scepticism ran deep, and by 2019 the company had built the unenviable track record of issuing a profit warning seven times in as many years.

Cevian, though, believed there was significant value in the business - it would just need the right management team to unlock Pearson's hidden potential.

Their investment thesis has been helped by the coronavirus pandemic, and COVID-19 could yet turn out to have been the catalyst for Pearson to finally turn the corner.

The booming online education market

Education is actually a thriving global business, but it’s moving from classroom and print products to online. That’s the critical trend Pearson needs to catch up with and latch onto. If Pearson turned itself into an online education company, its operative performance would improve, and the market would reward it with a higher multiple.

Right now, the company is already in a much better position to pursue such a reinvention.

Following the asset sales, Pearson has become a much slimmer company with a clear focus on education and a strong balance sheet. Two-thirds of its revenue is generated in the US, and the other major market is the UK (one of the world’s foremost education markets).

To advance the transformation, Pearson let go of its former CEO and replaced him with Andy Bird, a former executive of Disney International.

The new man at the helm should benefit from the changes brought about by the global pandemic. The education sector had long been criticised for its relatively slow technology adoption. This changed with the pandemic breakout: over 90% of the global student population have now switched to remote learning.

Operating in this new world is not without challenges. Pearson had made significant investments in building its online division and changing leadership, but these often enough resulted in write-downs and disappointments. New players have emerged in “EdTech” and these agile start-ups are a challenge for Pearson.

However, the company has assets that should enable it to succeed, after all.

Much as printed books are going out of fashion, owning the publishing rights for the books’ content represents a potential gold mine. These textbooks represent deep content repositories. Such content can be repurposed for online courses and blended learning environments.

The investors backing the new strategy believe that the content rights accumulated over decades are hugely valuable. Designing a digital degree course from scratch takes a long lead time. If you can repurpose existing content, it gives you a valuable edge over your competitors in terms of quality (tried and tested content) and timing (faster creation of courses).

Along the way, you can switch your services to new revenue models. Music has already shifted from physical singles and albums to digital downloads, and students could also move to an “all you can eat” subscription bundle for educational content.

Such streamlined models would also make content more accessible to students in countries with lower income, enabling Pearson to address a much wider audience.

What’s not to like? Suddenly, the outlook for Pearson looks a lot rosier than the depressed share price makes you expect.

Challenges ahead – but a strong balance sheet and low valuation

The online education market is complex and competitive, and there are significant operational risks associated with transforming a business model. Andy Bird, who took over his new post just two weeks ago, does have his work cut out.

However, he has some extraordinarily good raw material to work with. Pearson still ranks among the top dogs of its industry.

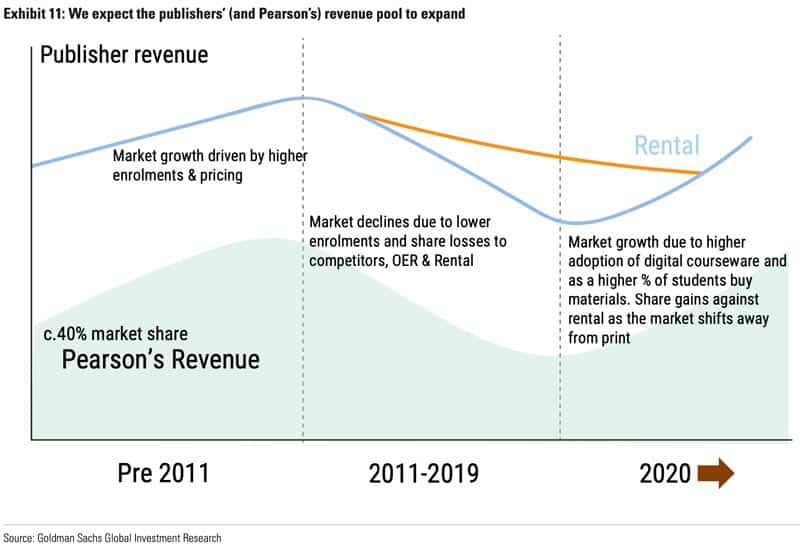

The pay-off, if it succeeds, could be huge. Pearson's shift to a more flexible, cloud-based system would pave the way towards becoming a scalable company. Margins would improve, growth would speed up, and the market would grant it a higher valuation multiple – potentially a triple-force pulling the stock price back up. As the following graph from Goldman Sachs tries to get across, Pearson could enter a decade-long growth period.

That’s what Cevian believes is going to happen. The “engaged” investor is still battling out various questions with other shareholders, such as potentially changing the company’s chairman. The first step has been made, though. Having a new CEO on board who has the backing of five shareholders that jointly control about 40% of the company is sufficient for Pearson to get off to a fresh start.

Andy Bird's tenure started with the announcement of results that show both the old problems and new opportunities. During the third quarter, group revenues shrank by 10% because of the slump in textbook sales. However, the online education division grew revenue by 32%. During the first nine months, enrolment in its virtual schools increased by 41%.

The online education business currently makes up only a fifth of sales, which is why it was not yet able to offset the decline in textbook revenue. Given its growth rates, that should change eventually.

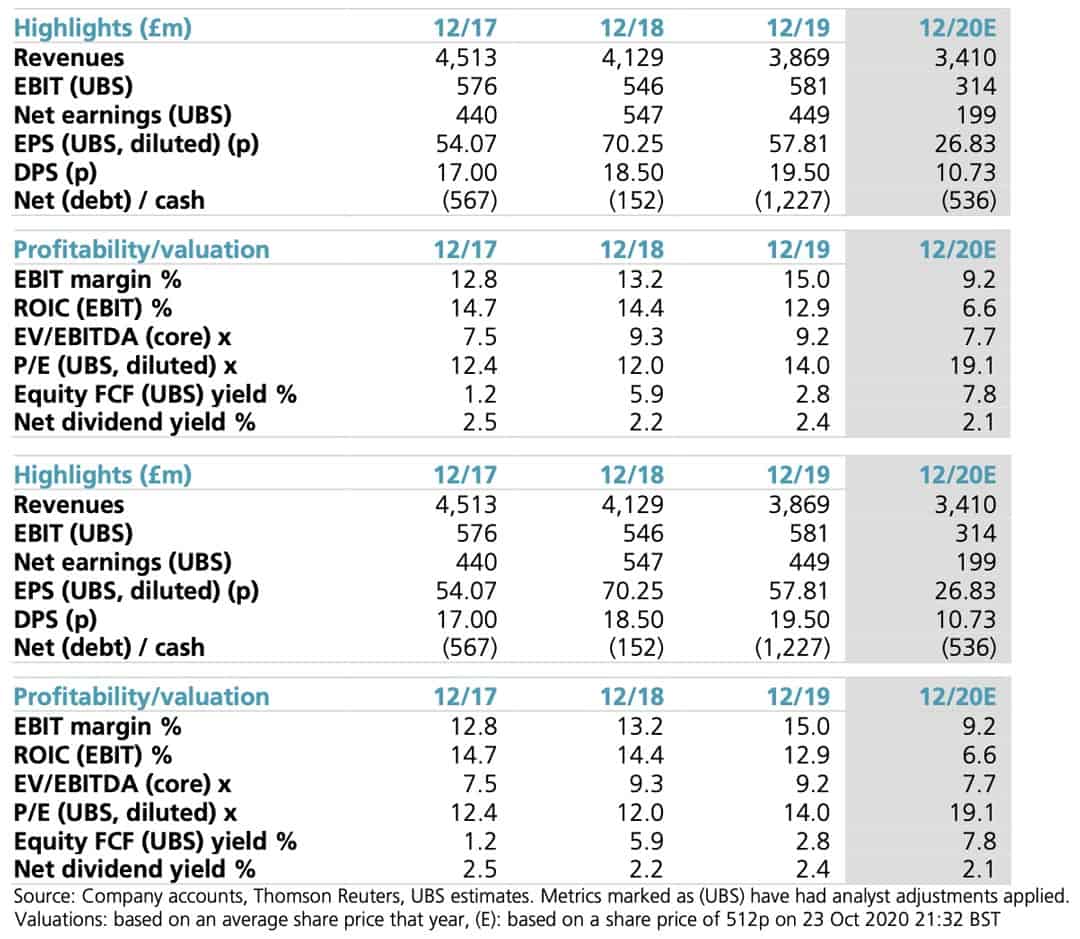

In the meantime, Pearson continues to sit on a cash reserve of GBP 1.6bn, which enables it to invest in building the new business. Its stock is cheap, provided the transformation succeeds. Based on the current stock price, it has an estimated 2022 cash flow yield of 8%. Net debt to EBITDA is lower than 1, and the stock is trading slightly below book value. These are valuation figures suitable for a dying old-economy company. If Pearson manages to shake off its image and ramp up its online education division, the stock could get new wind under its wings.

Cevian is probably onto something, even if it takes two to three years for the revised strategy to fully bear fruit. However, as of right now, you can probably buy the stock at a lower price than what the Swedes were happy to pay for their GBP 400m stake. That strikes me as a situation worth following.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post:

Get ahead of the crowd with my investment ideas!

Become a Member (just USD 49 a year!) and unlock:

- 10 extensive research reports per year

- Archive with all past research reports

- Updates on previous research reports