There is something special about buildings that ooze history and heritage. That’s why I mightily enjoyed living in the very same building where back in 1913, Aston Martin was formally set up. The old horse-stable turned engineering facility was later turned into a residential house and served as my London home for the five years from 2003 to 2008.

It did give me goosebumps when I considered that somewhere in my living room, the very first Aston Martin engine, in a car dubbed “Coal Scuttle,” roared into life in 1915.

Ever since I have had an interest in Aston Martin’s fate.

Reading up about it, I not only learned about Aston Martin cars, engines and race victories. I also stumbled across the fact that during the first 100 years of its existence, it managed to go bankrupt no less than seven times. Fabulousness in automobile history doesn’t necessarily equal financial success!

Aston Martin has a reputation as the car industry’s poster child for recurring financial trials and tribulations. It was, therefore, all the more surprising that the company recently managed to pull off a rather stunning Initial Public Offering (IPO). Through an IPO, a company goes from being a privately held company to being listed on the stock market with thousands of private and institutional investors buying shares in a placement. Despite valuing its shares at a sky-high valuation, investors snapped up the GBP 1,083m placement of shares within a single day (GBP 1 = $1.27).

Forgotten seemed those days when Aston Martin shuffled from one financial emergency to the next. Everything seemed to indicate that Aston Martin would start a new era as a successful, highly priced public company with fantastic future prospects.

Until its share price plummeted 30% during the first four weeks of trading, that is.

What had gone wrong, and why do the lessons learned matter to anyone who has ever considered subscribing to an IPO placement of a well-known, seemingly reputable company?

Fancy losing a third of your money in 4 weeks?

Good IPOs and bad IPOs

IPOs can be an opportunity for the public to buy into a growing, exciting company that so far had been privately held by its owners. This is more likely to be true when the IPO consists of newly issued shares, i.e., when shares are sold to raise additional money for the company to invest in its business.

However, IPOs can also be a mechanism for the company’s current owners to offload some (or all) of their shares. There is no requirement at all for an IPO to include the issuing of any new shares. Instead, it’s also entirely possible to base an IPO around the concept of existing shareholders selling off shares to other investors. In that case, the money from the IPO subscribers goes into the pockets of the previous shareholders who are selling, rather than into the company.

There is nothing wrong per se when the latter happens.

However, when someone is keen to cash out, the question is always, what do they know that the buyers of these shares don’t? The existing shareholders of a company tend to know that company from the inside out. When they sell, the question has to be asked: “Why?” You don’t want to be the one who gets left holding the bag when those who are in the know are cashing out.

In the case of Aston Martin, the basic constellation was as follows:

- On the surface, the company had staged an impressive turnaround. It went from a loss of GBP 163m in 2016 to a profit of GBP 87m in 2017. There are all sorts of growth plans, e.g., building a new SUV production facility in Wales to help achieve the goal of a 50% increase in revenue by 2020.

- The company is fairly heavily in debt and has comparatively little equity. On 30 June 2018, it had GBP 857m of debt and just GBP 153m of equity. Put another way, a single bad year like 2016 could wipe out the entire existing equity!

- All of the shares sold as part of the IPO process came from the two existing owners – two private equity firms from the Middle East and Italy, respectively – with zero of the IPO subscribers’ funds going into the company. Instead of propping up the thin equity base, the existing shareholders preferred to cash out for themselves.

With that last point in mind, you should now have a sense that at the very least, the Aston Martin IPO warranted some sceptical questioning. If prospects were so good, why did the major shareholders want to sell about a fifth of their shares?

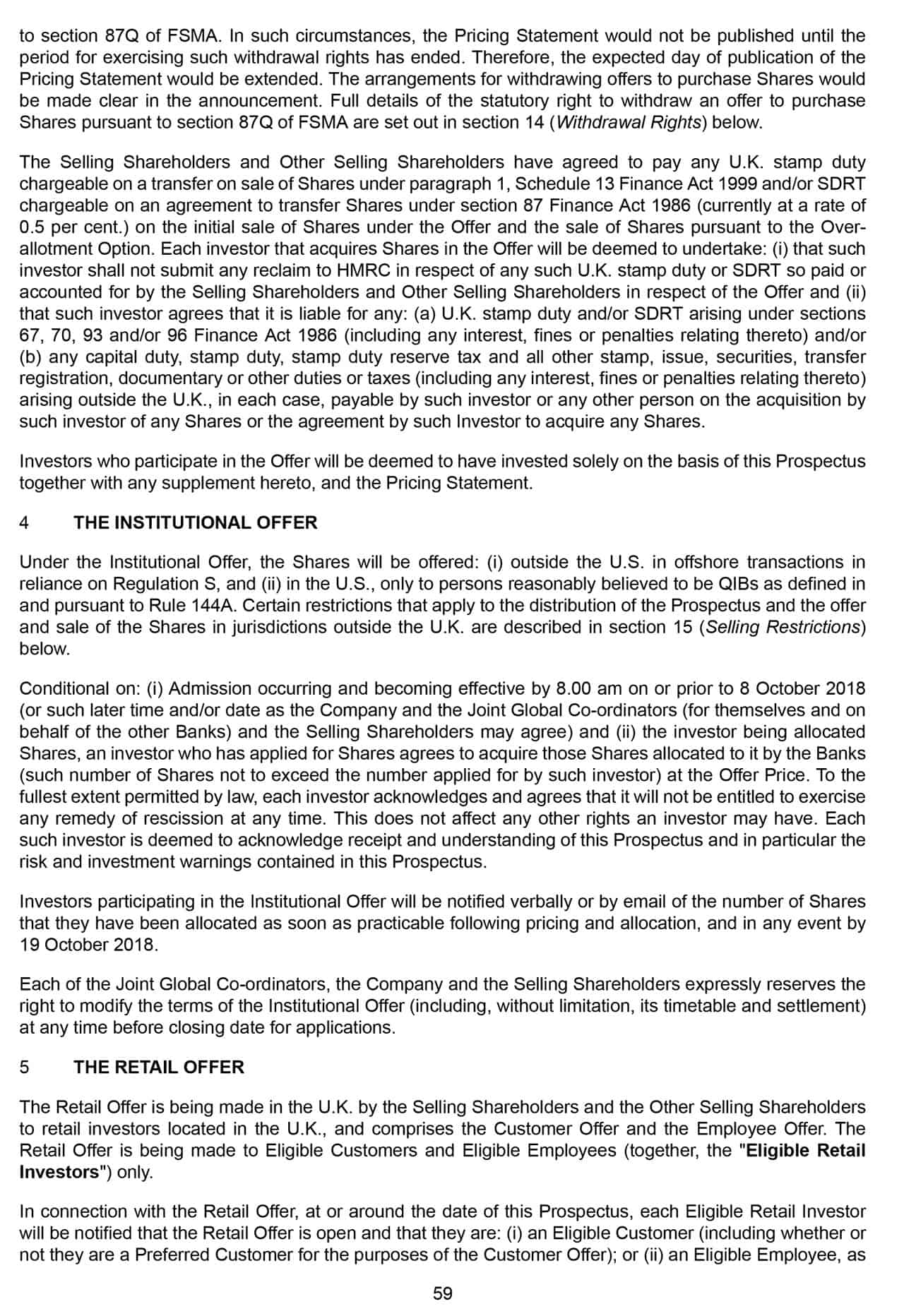

Reading the boring stuff

There are two ways for analyzing a company’s prospects.

You can look through PowerPoint presentations, corporate videos and similar superficial marketing material. This is the material that is bandied about by banks and brokers to place an issue. Much of which is also used by non-specialized journalists for writing their reporting and commentary ahead of the IPO.

OR you can delve into the legal documents that companies have to issue as part of their IPO process. These usually run to hundreds of pages, consist of dense text, and are written in incomprehensible legal mumbo-jumbo.

Reading this 321-page corporate document can easily make you go blind (or crazy)

There aren’t many investors anymore who take the time – and build up the skills – needed to read through the latter. However, it’s in these documents that the nasty stuff becomes more readily apparent.

If you really want to know what risks you are taking, reading through these legal document is much more valuable than to look at colorful infographics.

In the case of Aston Martin, all warning signs were there.

A company with near-perfect foresight (so they claim!)

In its accounting and legal documents, Aston Martin disclosed that it is “capitalizing” 95% of its research and development (R&D) costs.

If you haven’t come across this concept yet, it’s relatively easy to understand.

When a company spends money on R&D, it can treat the research costs in one of the following two ways:

- Expense it, i.e., deduct it from its income.

- Capitalize it, i.e., add it to its balance sheet as an (intangible) asset.

Ultra-conservative company owners would expense 100% of their R&D costs. R&D comes with no guarantee for a marketable product coming out of it. When in doubt, assume the worst and treat it as an expense.

The other extreme would be to assume that every single penny invested in research will lead to products that generate revenue. In that case, you could capitalize 100% of the R&D costs and keep them as intangible assets on your balance sheet.

In most cases, company owners decide to go a middle way. They figure out a percentage that, based on reasonable assumptions, reflects that some research will be successful, whereas other research will not lead anywhere. A reasonable portion of the R&D costs gets expensed through the profit and loss statement (which leads to a lower profit that year), the remaining percentage turns up on the balance sheet as an intangible asset. The intangible assets then get depreciated over their lifespan, which can range from a few years to decades.

Such aspects may not be the most exciting facts about a company that produces sexy cars, but they sure are at the heart of determining whether anyone should have ever subscribed to this company’s IPO.

Aston Martin, in its 2017 accounts, decided to capitalize 95% of its R&D costs.

Put another way, the company wants you to believe that 95% of its research is successful.

In comparison, car manufacturers around the world on average capitalize only 40% of their R&D costs.

If you like, you can also simply compare the 95%-figure to common sense.

Or, if you want to be a cynic, compare it to the company’s history of going bust seven times.

Aston Martin, that tiny car manufacturer which has only recently started to turn the corner, is supposed to beat the entire rest of the world’s car industry when it comes to how its R&D translates into successful products.

Yeah, right.

Cooking the books – the legal way

There is nothing legally wrong with Aston Martin capitalizing 95% of its research costs. It has actually done so for some years, with the percentage of capitalized R&D costs varying between 92% and 95%. You can read all about it if you make it as far as page 99 of the listing document.

Provided enough relevant people are giving “expert opinions,” you can then get highly paid corporate helpers, such as accountants, auditors and lawyers, to tick the relevant boxes. It’s all entirely within the scope of the law.

But how realistic is it likely going to work out in real life?

Also, what does it say about the culture of the company and the karma of the IPO?

Anyone who wants to make you believe that 95% of their research is successful, will also cut any and every other corner that is legally permissible to make their company look as good as possible.

I could continue listing manoeuvers the management of Aston Martin adopted to make their company look like a better prospect than it probably is. E.g., to justify its assumptions for capitalizing such a high percentage of its research cost, the company has plotted the launch of seven new car models in seven years; four of which are yet to come. That way, it can spread out its R&D costs in a way that makes it easier for the corporate helpers to tick all their boxes. Though what are the chances of a comparatively tiny car company launching seven successful new models in seven years? If one model doesn’t work out as projected, there’ll immediately be impairment charges on its activated R&D costs. Put another way, there’ll be extraordinary losses from, essentially, retrospectively expensing R&D costs.

Suffice to say, the market just doesn’t buy this story.

That’s why the share price plunged quite dramatically after the IPO. Such a high-profile IPO losing almost a third of its market value in the first four weeks of trading is quite catastrophic. Once the marketing hype settled, investors realized they had bought into a company that looked great on the outside, but whose engine wasn’t quite as strong and smooth-running as they believed.

Why are there no safeguards?

In any properly-run company, the board of directors would have at least a few independent non-executive directors, to make sure everything is being looked at without conflicts of interest tinting the judgment. Someone should have questioned these accounting assumptions.

In the case of Aston Martin, these racy accounting methods were put in place at a time when the company’s board had four directors each from both shareholders and not a single independent director.

Just before the IPO, the company reorganized its board to justify the stock exchanges requirement for independent directors. However, the accounting practices had already long been put in place by then; the auditors had signed off on past accounts, and the IPO documents had already been filed.

Make no mistake about it. These were all smart, legal, and well-timed manoeuvers to help lure investors and help the existing shareholders to cash out at the highest possible price. None of this is a coincidence.

If you get as far as page 183 of the listing document, you can even find out that the company’s CEO receives a bonus that is based on how high a price the existing shareholders get when cashing out their investment.

Literally, all the clues were there.

IPO subscribers ARE now left holding the bag

The Aston Martin placement took place at a price of GBP 19 per share. The company had attempted to place it at GBP 22 per share, but there just weren’t enough suckers at such a high price. So they cut it back a bit.

It subsequently fell to GBP 13.6, before recently recovering slightly to GBP 15.

Andy Palmer, the CEO, has come out to the defense of the IPO:

“We are not going to worry much on what the initial shares are doing.”

“We will always look over the longer term.”

“Bla bla blah.”

I doubt his employees will be quite as relaxed about the underperformance. They were given a cash bonus combined with an invite to invest it into their employer’s IPO. No doubt the company also wanted to incentivize its employees to talk about their share subscription elsewhere and that way, get friends, family and others to do the same. The Aston Martin IPO made for brilliant cocktail party conversations ahead of the first day of listing: “Are you in yet? It’s such a great brand, and then there is 007….” The owners of Aston Martin cars, too, were lured into subscribing to the share issue.

The company’s entire costs for carrying out the IPO: a whopping GBP 50m.

So far, the only real beneficiaries are the Kuwaiti and Italian private equity investors who cashed out a cool billion Pound Sterling, as well as the CEO who will receive a cash bonus.

Lessons to be learned

When private equity companies and other financial investors want to sell, you should check even more carefully ahead of buying.

There is a particular pattern when well-known companies like Aston Martin come to market. They often abuse the brand name credibility of their product to lure investors into an emotive buy. No doubt, without 007 and its brand history, this placement would not have succeeded in the first place. Sexy products can blind investors to dodgy financials.

The placement still took place because banks, brokers and fund managers ultimately all conspire to make money off the back of private investors when they are given an opportunity to do so. All that counts for them are short-term profits.

Aston Martin is a perfect example for financial snake-oil peddlers hiding behind the cloak of complying with listing rules. But just because a company ticks all the boxes of the IPO process, the number one rule of investing remains firmly in place… “Caveat emptor,” buyer beware!

The process of taking good care of your money before investing in an IPO may well include the need to read through hundreds of pages of documents. Or, if you don’t have the time for that, find someone who does. Spoiler alert: saying this is obviously aimed at shamelessly promoting my blog.

If you don’t do extensive homework before investing, more cunning players such as private equity vampires may well end up drinking your lifeblood at their next cocktail party.

Shaken, not stirred!

Best regards

Swen Lorenz

Undervalued-Shares.com

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post: