Image by Gil C / Shutterstock.com

Not every public company is listed on a stock market. Shares can simply change hands in private transactions, without having to comply with the many rules and regulations of recognised stock exchanges.

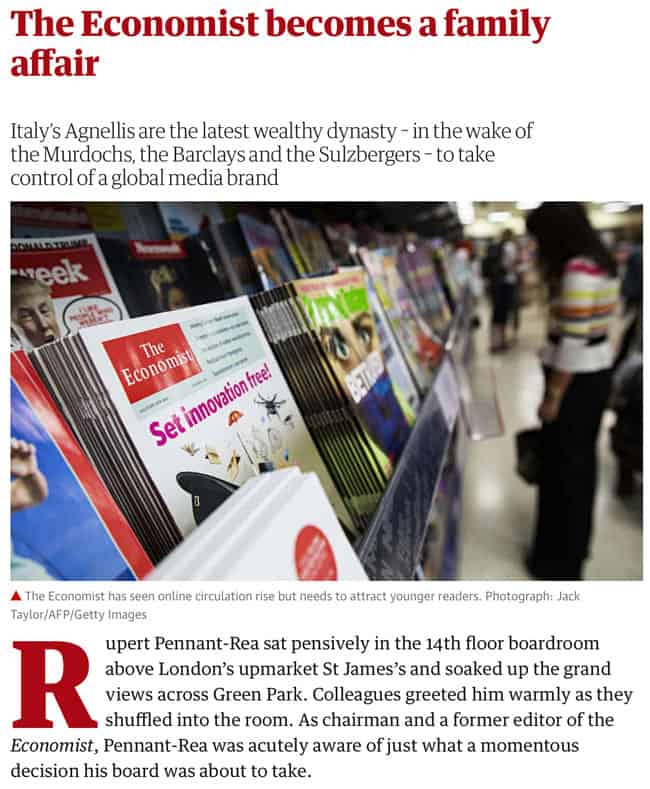

Such is the case with The Economist Group, the company behind one of the world's most influential magazines. While you sometimes get to read about the company's business, e.g., in The Guardian or the Financial Times, no one ever seems to look at its stock.

To the best of my knowledge, this is the first-ever article that investigates the issue of buying a share in The Economist.

A world exclusive (of sorts)

As my long-standing readers will know, I find it exhilarating to research investments that are hidden, exotic, or complex. Point me towards a difficult-to-research stock and I'll go on a quixotic mission to find out all there is to know - even more so if someone has an interest to hide facts or block access to information.

I had long wanted to do a deep dive into The Economist as an investment, probably as far back as 2005. I've got a great deal of respect and admiration for this publication ever since I started reading it in high school, plus it has a difficult-to-trade stock - an irresistible research project to get my teeth into!

You'll find I have gone to great lengths to compile this article:

- I attempted to attend the July 2021 shareholders meeting as a journalist to observe and ask questions. I thought that a company run by journalists would understand that other journalists were eager to shed light on a company that shapes the views and actions of many of the world's most powerful people. Sadly, but not unexpectedly, my access requests did not elicit a reply.

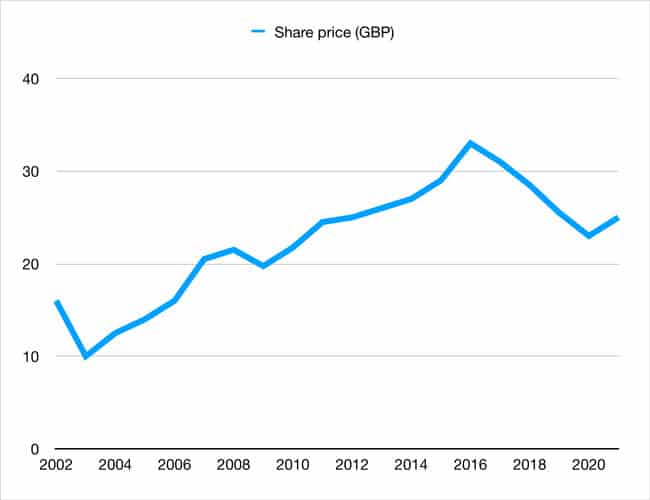

- To show the stock's historical performance, I manually created a chart from annual report data as far back as 2003. How did the journalists who bestow their wisdom on the business world fare in running their own business?

- To help those of you attempting to buy a few shares, I compiled instructions on how to approach a potential purchase. Spoiler warning: Chances are you won't be overly welcome as a shareholder, even if you find someone who is willing to sell.

Admittedly, today's Weekly Dispatch will have less of an investment value. Buying stock in The Economist will at least be a lot of work, and may even prove outright impossible (at least for the time being).

Still, shedding a bit of light on this peculiar company makes for a fun and interesting mental exercise, which I know many of you enjoy. I've received enthusiastic reader feedback on some of my other off-the-beaten-path investment stories, such as the exotic securities that give you a kind of co-ownership in the Wimbledon tennis club. Also, The Economist is, after all, a publication that sits at the heart of financial markets and operates one of the world's best-known media brands. I bet a significant percentage of my readers will be subscribers of the magazine, or at least casual readers.

Last but not least, a proper IPO and listing on a recognised stock exchange may yet happen in the future. The Economist Group is now at a point where something revolutionary could happen to its ownership structure. Going public was once considered inconceivable for Goldman Sachs (ISIN US38141G1040), too, but eventually, it did. Its governance structure had outlived its time, and (possibly more importantly) there was lots of money to be made by modernising it.

Before we look at The Economist's potential future, let's look at its history.

A Scottish hat maker kicked it all off

The Economist started as a broadsheet in 1843, created by Scottish economist and hat manufacturer James Wilson. Its founder wanted to drum up support for opposing the British Corn Laws. The first issue, which appeared on 2 September 1843, is available as a free downloadable PDF.

Over time, the publication greatly expanded the scope of its coverage. Its weekly format turned it into a kind of Reader's Digest-equivalent for the political and financial elite of Britain and, later, the world. It primarily features world events, politics, and business, but also science, technology, books, the arts, and the world's most interesting weekly obituary of a notable person.

Throughout the decades, The Economist managed to hold on to a number of quirks: Its articles don't have any bylines (i.e., the author is hardly ever mentioned by name; instead, articles are written by "The Economist"), and it also makes a point of having an opinion, rather than attempt neutral reporting. The Economist has been called "the world's best magazine" on more than one occasion, and probably rightly so.

It's hard to fathom The Economist's small start. A hundred years ago, it was a magazine that primarily focused on matters happening in London, with a recorded circulation of just 6,170 copies. It struggled financially and required a bailout in 1928.

It was not until the 1950s that The Economist reached a circulation of 50,000. That decade, the Financial Times bought a 50% stake in its share capital. During the ensuing decades, The Economist became one of the few truly global publications, with copies available at far-away airport newsstands and hotel lobbies.

Even yours truly once featured in The Economist, when it recorded my epic struggle with corrupt politicians in the Galapagos Islands (needless to say, at the time I was more than a bit proud of having made it into one of my favourite publications!). The article resulted in the single most successful public fundraising drive ever for the scientific foundation that I managed at the time, with checks and bank transfers arriving from around the world – testament to The Economist's well-heeled readership!

Much as I've got my own tripe with media bias in general and The Economist's editorial stance on Brexit in particular, you cannot argue with its numbers and the quality of its reporting. The Economist continues to attract the best talent of the journalist market, which produce some of the world's highest-ranking outputs. Its social media followership amounts to 56m, and 1.1m people around the world have subscribed to the magazine in either print or digital form. In its fiscal year 2020/21 (ended 31 March 2021), subscriptions increased by 9%, the largest ever year-on-year increase. The recent success is easy to explain: the magazine's articles tend to be on the long side, and the pandemic gave people plenty of time to read as well as curiosity about what was going on in the world.

The pandemic helped The Economist grow its business (Image by dennizn / Shutterstock.com).

Besides the number of its readers is the quality. I doubt there is a corporate headquarter, ministerial office or billionaire's home where The Economist isn't read, at least occasionally. The Economist remains one of the world's great opinion-shapers.

Alongside the weekly publication, the team of The Economist have created a spin-off magazine (Economist Life), a book series (including the wonderful "Style Guide" on the proper use of the English language), the Economist Intelligence Unit as a research division for corporate and governmental clients, and a number of high-profile inventions such as the invaluable Big Mac Index.

The Economist also has its own landmark building in London, the Economist Tower on St James's Street. An architectural marvel with its own peculiar history, it was sold a few years ago and it's now once again named after its architect (Smithson Tower), but every Londoner I know keeps calling it by its old name.

Who pulled the strings of all this?

The Economist Group is owned by no less than 1,000 shareholders, though some shareholders have more say than others. Throughout its 178-year history, the company has enjoyed a remarkably stable ownership. The family of its founder was in control until the 1928 bailout which was funded by a number of wealthy families, the Financial Timesheld on to its stake for eight decades, and some of the families that funded the bailout 93 years ago are still invested and on the board.

To be a shareholder of The Economist Group is to join an illustrious circle, as you will see.

Not your average group of shareholders

Owning an influential publication is something the billionaire class has long taken a liking to, and stakes in publications with significant heritage are often kept as part of the heirloom of dynastic families. Even in this day and age, owning a major publication is the ultimate calling card in business and politics. It is the media equivalent of owning an estate in Bordeaux.

- Jeff Bezos famously purchased the Washington Post.

- Salesforce founder Marc Benioff and his wife Lynne purchased Time

- Daniel Kretinsky, the Czech coal and gas magnate who shot to fame as a corporate raider, snapped up a piece of Le Monde.

- New York's Sulzberger family has long run The New York Times.

- Rupert Murdoch still owns The Times, The Sun and the Wall Street Journal.

- Britain's Lord Rothermere controls the Daily Mail.

- In the US, the Hearst family is still a significant shareholder in the Hearst Corporation founded by the legendary newspaper magnate, William Randolph Hearst.

When a large stake in The Economist Group came up for sale, Michael Bloomberg, Thomson Reuters, Axel Springer Group and the Hearsts all showed an interest, as chronicled by Politico on 25 July 2015. The Financial Times, too, was keen. The Pink Lady had considered a full takeover of The Economist, but its interest was rebuffed and it subsequently decided to sell its 50% stake.

A dynastic European billionaire family eventually landed the deal.

Exor (ISIN NL0012059018) is the investment company of Italy's Agnelli family, founders of the Fiat car empire. John Elkann, grandson of the legendary Gianni Agnelli and CEO of Exor, had been on The Economist Group's board since 2009 (he joined when he was just 33). The Agnellis already owned a 4.7% stake, which put them at the centre of a shareholder roster that for the past century included the Rothschilds, Sainsburys, Cadburys, and the Schroder family – the crème de la crème of British society, all of whom had joined as part of the 1928 bailout.

Apparently, Elkann had shown an "agreeable personality" and "a constructive approach to the company's challenges" during board meetings, which gave him an edge when Pearson Group (ISIN GB0006776081), the owner of the Financial Times, cleared out its portfolio of print publications and put its 50% stake in The Economist Group up for sale. Lynn Forester de Rothschild, a long-standing board member and former fundraiser for Hillary Clinton, reportedly had a major say in who was going to be allowed to buy the stake. The British arm of the Rothschild family, represented by Lynn, held a 21% stake which made them the second-largest shareholder.

John Elkann (2018 image) - Image by cristiano barni / Shutterstock.com.

Exor bought the largest part of Pearson Group's stake and upped its own stake to 43.4% of the company's share capital, well ahead of the Rothschild family's 21%. It paid GBP 287m for the stake, implying a valuation of ≈GBP 750m for the entire company. Rather unusually, the remainder of the shares put up for sale by Pearson Group was bought by The Economist Group itself – stock worth GBP 182m, or ≈20% (!) of its entire share capital. Interestingly, the company decided to keep the stock in treasury; something I'll get back to later.

This was the biggest change in ownership since 1957, when the Financial Times had acquired its stake. However, neither the Agnellis nor anyone else can currently exert true control over The Economist Group, which is set within a complex trust structure and comes with multiple share classes. Even Pearson, despite owning 50% of its capital, was legally deemed a "non-controlling shareholder".

The Economist Group's current governance structure was created in the late 1920s, to help keep its editorial team truly independent (or so it was claimed). Important rules include:

- No shareholder is allowed to exert more than 20% of the votes.

- No one is allowed to own more than 50% of the share capital.

- A special share class, the trust shares, gives four trustees "super-powers". These include an ability to i) block any change in share ownership, ii) block the appointment of the chairman, and iii) block the appointment of the editor. It would require 75% of the share capital to change these rules, which would be nigh on impossible given the limitation of voting rights to 20% per individual shareholder. Exor and the Rothschilds own 64.3% of the share capital, but they could only muster 40% of the votes.

Why is the company run on such a strange governance model, and why on earth would anyone spend several hundred million on buying 43% if there is a 20% cap on voting rights as well as the incalculable risk of a group of god-like trustees?

As I said, The Economist Group is a company unlike others. Or as the Financial Times put it in a 26 July 2021 article: "Few media companies are as idiosyncratically structured as the Economist Group." Quite possibly, it's the ultimate British private members' club.

The Guardian published an in-depth article about the 2015 ownership changes.

Elkann's commercial rationale

Even at a billionaire's investment vehicle like Exor, an investment increase of GBP 287m will have faced financial scrutiny. Billionaires are not known to waste money, and Exor as a publicly-listed company has outside shareholders to report to.

When Exor upped its stake in The Economist Group, it did so based on a valuation around the GBP 750m mark. At the time, the company achieved GBP 60m operative profit on revenue of GBP 324m. Net profit that same year was GBP 45m. On the one hand, the print media sector faced major challenges and the 43% stake was going to give a limited amount of control. On the other hand, this was a business with a 15% net margin and sold at 17 times earnings. It wasn't a screaming bargain, but Exor got itself a pretty decent deal.

Only a fool would assume the Agnellis would ever have overpaid to boost their egos, like some other billionaire families did with their recent media purchases. John Elkann became Gianni Agnelli's chosen successor at age 28 because the old man had identified him as the most commercially astute member of the family. Not only did Elkann pull the family fortune back from the brink, he has taken it to new heights. Given that he was already on the board of The Economist Group, it seems unlikely the additional investment was driven by a clamour for prestige.

Why the purchase, then?

An article that appeared in the Financial Times on 23 April 2020 provides some insights into Elkann's likely rationale. At the time, Exor purchased another significant legacy media asset, Italy's large but deficit-ridden newspaper group GEDI.

"But those who know Mr Elkann well say he pursued the acquisition for clearheaded reasons. 'This is not a trophy nor is it nostalgic, it's an investment,' one person close to Exor said. 'John likes media, but he wouldn't do it unless he believed he could make it a commercial success.'"

Why does the Agnelli family's strategic thinker take an interest in legacy media brands?

It's quite possible for Elkann to follow the Sulzbergers, the dynastic family that succeeded against all odds and took The New York Times Company (ISIN US6501111073) to new heights entirely. Following the company's near-crash in the 2000s, the Sulzbergers managed to increase its value by a factor of nine over the past ten years. The Economistshould have some pricing power, and once you combine (for example) 3% p.a. pricing power with 3% p.a. unit growth in a business that is increasingly digital, you are ending up with a fast-appreciating business.

The New York Times is an American newspaper, but it offers tremendous scalability due to its uniquely global appeal. Factors that have helped the company succeed include the ongoing growth of digital subscriptions and the launch of other digital products (anything ranging from specialist newsletters to crossword puzzle apps). Seeing how profitable it can be to digitise and scale up a legacy media brand name, it becomes easier to understand what attracts a billionaire investor to a heritage-rich print publication.

The Financial Times article about the GEDI transaction yields further clues:

"Mr Elkann is optimistic the business can return to profitability. 'We are conscious that this is a contrarian acquisition given the headwinds facing the newspaper industry,' he wrote in a letter to Exor's shareholders in March.

'However, we believe that, despite these challenges, news organizations providing quality journalism will continue to attract and grow paying readers.' Improving the digital platforms of GEDI's publications, cutting duplications across local newsrooms and slimming down the overall structure will be initial areas of focus, said two people briefed on Mr Elkann's plans.

On Thursday he said 'the road ahead will be a demanding and extraordinary one . . . we have chosen to embrace innovation and digital transformation', without providing further details on his plans."

Does this imply that The Economist Group is also going to ramp up its digital abilities and develop bigger ambitions?

The company is actually already very much on that path, as can be seen from its own statements. It may not be listed on a recognised exchange, but it voluntarily adopted some governance measures akin to those of a publicly-listed company, such as a very informative annual report published online. For anyone who wants to keep on top of digital media and the news business, this report makes for both obligatory and exciting reading.

As The Economist Group's CEO, Lara Boro, wrote on page 11 of the 2020/21 annual report, the company aims "to provide new and more integrated digitally-led propositions to our customers, and to reach new audiences. In the last year we've taken significant strides towards transforming the business so that we can unlock that opportunity."

The editor in chief, Zanny Minton Beddoes, added:

"Our digital transformation has accelerated dramatically. For some time our journalism has flourished on outside platforms: Economist Films has almost 2m subscribers on YouTube; our podcasts attract more than 3m listeners a month; our social-media channels have 56m followers. Yet our own digital products, particularly our apps and website, were laggards. That is now changing fast. The Group's commitment to faster product investment, outstanding new tech and product leadership and intensive collaboration between the editorial and business sides of the Group will ensure a rapid improvement in our digital capabilities.

This is essential to our future: the majority of our new subscribers are now digital-only. Reinventing Economist journalism for a digital-first world is our biggest challenge for the coming years. We need to be clear about what makes us stand out: insight not instant news; quality, not quantity; rigour and wit. And we will need to provide our journalism to our subscribers in a form and at a cadence that suits them. For some that will still be the weekly read; for others it may be a constellation of podcasts. The opportunities are tremendous, and we are determined to make the most of them."

(You can download all annual reports dating back to 2003; its back issues read like a history of the media industry's ongoing transformation from print to digital.)

Each annual report also includes the "indicative share price" of that year. Once a year, accounting firm EY provides The Economist Group with an estimate of its share value. To be precise, it's the indicative value of the "A" class of shares, which is the only class of which shares are in public circulation (Exor holds 100% of the "B" shares and the "Trustee" shares are held by the trustees). Shareholders are free to buy and sell at any other price, but it's likely the official indicative share price plays a guiding role in all transactions.

Since 2002, this is how the indicative share price has developed.

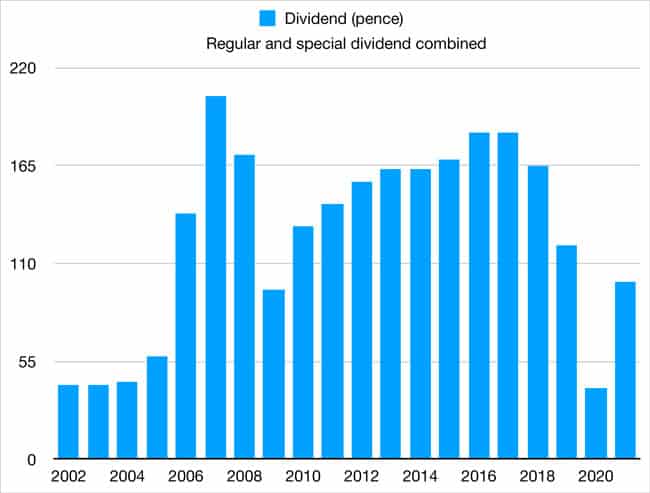

In terms of dividends, this is what The Economist Group has yielded for its shareholders over the past two decades.

Since 2002, The Economist Group has paid an average annual dividend of ≈GBp 125 (= 125 British pence). Its share price averaged ≈GBP 22.50 per share. At the risk of making a handwaving assessment, most investors who bought during this period will have sustained their capital and earned a ≈5% dividend yield. Not a bad performance at all, especially in an industry that has seen many players go out of business entirely and considering that The Economisthas always been a bit of a slow-moving behemoth.

A more critical assessment would be that over the past ten years, The Economist Group's stock has not increased in value at all, while the Sulzbergers have enjoyed a ninefold rise of their company's stock price. From that perspective, The Economist Group has been a total dud.

Exor shareholders, too, have a right to ask questions. For its "A" shares, Exor paid GBP 36 per share, which is higher than the highest price ever assessed by EY. The stock has lost approximately 30% of its value since the stake increase (though it will have earned dividends in the meantime). During the same time, the MSCI World Index has gained ≈94%. Then again, given the investment makes up 1% of Exor's investment portfolio, will anyone have even noticed?

In terms of the long-term performance, it's all a bit of a mixed bag and difficult to make an objective assessment. More importantly, though, where will it go from here?

"Do as I say, not as I do"

Let's face it, shareholders such as the Rothschilds or even Exor could decide to simply sit on their investment and leave things as they are from now until the end of days. After all, The Economist Group is profitable and its business is growing. Who could possibly have a right to complain?

Then again, John Elkann is John Elkann. Aged 45, he is probably about to enter the most productive and successful decades of his life. Ranked as "one of the world's most influential managers" by Fortune magazine before he had even hit 40, Elkann is the kind of guy who meets President Xi when the Chinese leader comes to Italy, or gets invited to Jeff Bezos' Mars conference in Florida. He doesn't strike me as someone who wants to mollycoddle with board members and drink tea, but as somebody who, by way of wealth, background and connections, is eager to shape things.

Depending on how you look at it, the current valuation of The Economist Group is either cheap or expensive:

- It's expensive if you compared the company's current market cap to its 2021 net profit of GBP 17.4m. For an unlisted business with a governance structure that severely hampers not just owner control but also stock liquidity, I'd probably pay GBP 10 per share, at best - far from EY's GBP 25.

- It's cheap if you look at the company as a unique heritage brand that can be scaled up globally in the digital realm. The Economist Group could probably pull off something comparable to The New York Times Company's market cap of nearly USD 9bn. In terms of potential, the share is probably still maddeningly cheap at a price of GBP 25. Its current price also shows just how much of a discount the market applies when there are outdated governance structures.

Alas, how likely is a significant change at the company? After all, it's mired in an anarchic governance structure that was specifically designed to prevent, or at least massively slow down, change.

The new Volkswagen?

German blue chip Bayer AG is today where Volkswagen was three years ago. Its reputation in tatters, thousands of lawsuits, a bombed-out share price – but a highly profitable underlying business!

2022 should bring a turnaround for the battered company, similar to the one seen at Volkswagen.

My latest report, out today, has all the details.

The new Volkswagen?

German blue chip Bayer AG is today where Volkswagen was three years ago. Its reputation in tatters, thousands of lawsuits, a bombed-out share price – but a highly profitable underlying business!

2022 should bring a turnaround for the battered company, similar to the one seen at Volkswagen.

My latest report, out today, has all the details.

In one of those ironies in life, The Economist Group today features the exact governance features that its own journalists have criticised for many years:

- Restrictions on who can exert how many votes.

- Trustees who, to some extent, are shielded from accountability to shareholders.

- Restrictions on who can even buy shares.

Indeed, even its journalists agree that such governance features are no longer desirable – not for the company, nor its shareholders or society as a whole.

As The Economist wrote in its Schumpeter column "Shareholder democracy is ailing" on 11 February 2017:

"For many in business the decay of shareholder democracy is irrelevant. After all, they argue, investors own lots of other securities—bonds, options, swaps and warrants—that don't have any voting rights and it doesn't seem to matter. At well-run firms such as Berkshire, shares with different voting rights trade at similar prices, suggesting those rights are not worth much. Some managers go further and argue that less shareholder democracy is good, because voters are myopic.

It doesn't take a billionaire to poke holes in this logic. For economies, toothless shareholders are damaging. In China and Japan firms allocate capital badly because they are not answerable to outside owners, and earn returns on equity of 8-9%. A study in 2016 by Sanford C. Bernstein, a research firm, got Wall Street's attention by calling passive investing 'the silent road to serfdom'. Without active ownership, it said, capitalism would break down."

In its 19 June 2021 Leaders column "Investors in technology need to pay attention to corporate governance", The Economist warned against straying from the principle of one share, one vote and putting too much power in directors with super-voting rights:

"The last reason to watch out for tech firms is their bosses. Dotcoms and their corporate cousins are often still run by their founders. Many of them have controlling stakes, thanks to souped-up voting rights. These entrepreneurs tend to have a messianic confidence in their own abilities and a fortune to match. The heady potion of control, wealth and self-belief can lead bosses to brush aside all criticism and to look upon rules as things for other people."

On 7 February 2015, the same Leaders column ("Capitalism's unlikely heroes") spoke of the value of activist investors shaking up such outdated governance structures:

"As inventions go, the public company is one of capitalism's greatest. Initial public offerings promote innovation, by providing an exit route for entrepreneurs; being listed makes a firm open to scrutiny; and ordinary people have a chance to invest in capitalism's wealth-creating machines.

…

At the same time, tycoons in Silicon Valley have often turned outside investors into second-class citizens, by creating special voting rights for their own shares.

…

Activist hedge funds take small stakes in firms and act like political campaigners, trying to win other shareholders' support for their demands: representation on companies' boards, cost-cutting, spin-offs and returning cash to shareholders.

…

About a tenth of big American firms, and even more smaller ones, still employ tactics like 'poison pills' and staggered boards that shelter incompetent managers."

Not all of these words apply 1:1 to The Economist Group, but a lot rings familiar:

- A protected class of managers.

- Special voting regulation, instead of one share, one vote.

- Hoarding excess cash, thus diluting returns.

Remember those ≈20% of the company's equity that The Economist Group itself bought back? These shares still sit in the company's treasury. They are worth nearly GBP 200m, and their votes have effectively been pulled from the pool of shares that can vote. A company owning such a large stake in itself is something you'd expect to find among Russian companies controlled by oligarchs, rather than at The Economist Group.

Why not return these funds to shareholders instead of locking them up inside an outdated governance structure? This is a question that The Economist Group shareholders should ask but of course, they won't. In a private members'-style company like The Economist Group, no one will want to be seen as being difficult. Someone like yours truly, who could have asked interesting questions at the annual general meeting, will never be admitted.

It's all perfectly legitimate and legal, given that every current shareholder will have bought into the company when the governance structure was already in place. However, it does contribute to the hypocrisy that runs deep in London's left-leaning media circles. I socialise a lot in London, and media circles are my natural home when I am in the Big Smoke. Whether they will get away with this hypocrisy much longer remains to be seen. If I were a shareholder, I'd view such an obvious contradiction in public position and private action as a risk. My ramblings are read by few, but some of The Economist's competitors could eventually take a mischievous interest in the matter. How long until a competitor or rival takes delight in naming and shaming the hypocrisy of The Economist Group, and pinning it on John Elkann and other posh shareholders? Elkann stepped down from the board in September 2020, but he will have his representatives on there.

Even without that, the matter already affects how the publication and its output are perceived and what impact it has. There used to be a time when I – like many others – viewed the opinion of The Economist as the equivalent of the wisdom of the elders. Like many others, I now take the views of most mainstream media journalists less serious, following how blatantly obvious it has become that they all too often preach one thing but do something else in private. In the Internet age, there is less hiding.

Only a strong, well-established shareholder like Elkann would be able to put a foot in. The Economist Group could flourish even more – financially, but also in terms of positive impact – if it reformed itself and IPOed. As to the benefits of a company's proper public listing, check back to The Economist's praise quoted above.

External shareholders of Exor would probably agree that 93 years after creating the current governance structure, it's high time for a once-in-a-century change. Their money (well, 1% of it) has been tied up in an investment that since 2015 has lost money when world markets moved up rapidly.

Modernising the governance structure would open up all sorts of opportunities, such as raising growth capital, an immediate rise of the stock price, and an improved reputation of the publication (especially if the company said publicly: "Sorry, we fell a bit behind the times, but from here onwards we'll eat what we preach.").

Will it happen? Won't it? I have no idea. I would have asked, but I wasn't let into the club.

Speaking of which, I know for sure that some of you will want to buy some stock. I do have readers who enjoy owning one stock in every company. If you are up for a challenge, here is what you can do.

Revealed: All shareholders, now easily downloadable

Up until last year, the shareholder registry of The Economist Group was "public but hidden":

- "Public", because the company was large enough to have to file a copy of its shareholder registry with the UK's company register (Companies House) each year.

- "Hidden", because the company managed to exploit a little-known quirk of Companies House. For lengthy shareholder registries, one could avoid a listing in the publicly-accessible electronic Companies House database. Instead, anyone interested in a copy had to request Companies House by phone or through a personal visit to post a CD-ROM (!) with the document (and pay GBP 15). Needless to say, this acted as a huge filter and meant no one ever looked at it.

My attempt to get hold of The Economist Group's shareholder registry last year was scuppered by the pandemic, when Companies House shut down its CD-ROM service for over a year.

Good news came in a few months ago, though. Thanks to the pandemic, ALL documents stored at Companies House are now available online. If you want a copy of all shareholders of The Economist Group, you can download the 200-page document with a bit of effort from the Companies House website, or with just one click from Undervalued-Shares.com (it's a public document anyway, so download it and see if your neighbour is a member of the club).

Names, shareholdings – it's all in there.

Without a doubt, some of these shareholders would be open to sell if only anyone ever approached them with an offer. All the more so if someone offered, for example, double the normal price just to convince someone to sell. In the day and age of LinkedIn and other databases, the contact details of many of these shareholders will be available online to anyone who looks. Plus, there are bound to be heirs, ex-employees, ex-spouses and other shareholders with limited connection to the company, who will be more likely to sell. Who knows, maybe a public tender offer could even yield some serious stock?

You'll still have to get approved by the trustees, but that'd be interesting to experience firsthand. Will they really turn someone down? On what basis, given that not even a 43% shareholder could feasibly have any influence on the editorial stance? Could consent be reasonably withheld and in what light would The Economist's writing about second-class citizens among shareholders be viewed subsequently? Will some journalist at The Guardian attempt to buy stock and write about it? Those Guardianistas are known to be looking for a good story about Britain's financial elite.

OTC-traded companies are increasingly attracting interest in online discussion fora such as Reddit, and it's probably just a matter of time before The Economist Group will have to deal with more questions about its stock. It's inevitable that this will happen sooner or later, so don't shoot the messenger.

It's such a great company and amazing product that I'd personally love to see it move beyond its current structure. Having The Economist Group traded on a stock exchange would enrich the variety of publicly-listed companies that ordinary people can invest in. Again, I am referring back to one of the quotes mentioned above.

Watch this space for further developments – or a continued lack of news

Honestly, I have no idea whether today's Weekly Dispatch is going to turn out prophetic or an absolute dud.

Keep in mind that companies like The Economist Group may simply not think along the lines of conventional thinking. This is a publication that in the early 1990s ran an advertising campaign that proclaimed "The Economist - not read by millions of people". Snob appeal has long been a part of The Economist's success, and it may well continue to do so.

If it did want to change, now seems like an ideal time. The company has moved to a new headquarter, it has a new, dynamic major shareholder, and the market is receptive to heritage media brands that are looking to fund ambitious growth plans.

I don't own any shares, but if The Economist Group were to list, I might actually buy some.

In the meantime, I'll continue to enjoy my subscription. The Economist is the world's best weekly magazine after all, that's for sure.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post: