Image by Tada Images / Shutterstock.com

During his first election campaign and term, president Trump called it "the failing New York Times".

He was wrong.

In fact, shareholders of the "Gray Lady" have done rather well.

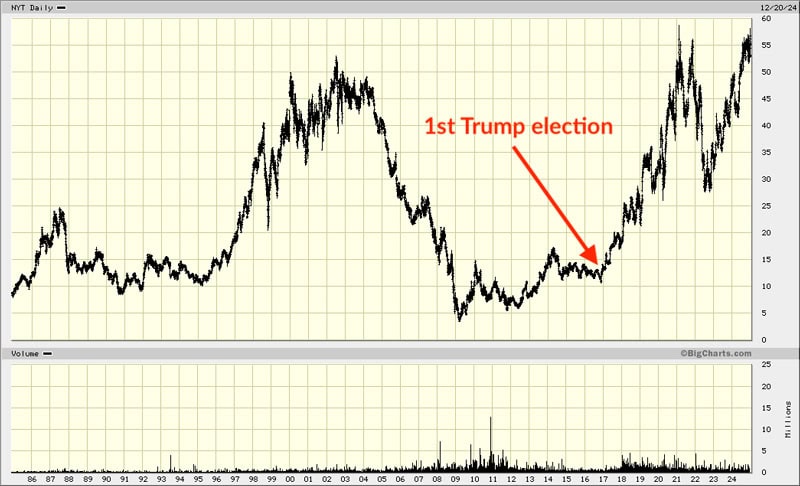

At the inception of Trump's first term, the share was trading at USD 13.

Today, it's at USD 52.

This success is remarkable given that the newspaper sector has been in turmoil and decline for the better part of two decades.

Today's Weekly Dispatch takes a roving look at The New York Times' past, present and potential future.

The New York Times Company.

Newspapers in the digital age

Any analysis of The New York Times Company (ISIN US6501111073, NYSE:NYT – "A-shares") has to consider the industry's broader context since the turn of the millennium.

Think back to a time before anyone even thought of the iPhone and when many still used dial-up Internet. In 1999, the daily newspaper industry in the US consisted of 1,600 dailies that generated circulation revenue of USD 10.4bn and a further USD 46.2bn in advertisement revenue. The industry was bigger than broadcast and cable television combined.

The 25 holding companies that controlled most of the sector were insanely profitable. Average profit margins were 28.5% that year, mostly driven by ever-increasing rates for advertising.

Back in those days, Warren Buffett put on public record: "I can't think of many other businesses that, if I just owned one asset over my life, I would rather own than a newspaper in a single-newspaper town."

Rupert Murdoch once described his stable of newspapers as "rivers of gold".

This was an industry with virtually no R&D costs. Instead, much of the money went into the pockets of the newspaper owners and their relatively well-paid staff.

Some of these companies may have had it too good. The management of some of the leading newspaper companies at the time got away with putting in place (or maintaining) dual-class stock structures.

The Ochs-Sulzberger family that is in charge of "The Times" (as The New York Times calls itself) is just one of several prominent examples where outside shareholders were left at the mercy of long-standing family shareholders. This didn't bother anyone during the good times but became an issue when the sector became more challenging.

Google and other online media offered advertising that was much more targeted and effective, which is why they managed to quickly eat into the newspapers' advertising income. Newspapers also lost revenue because of some subscribers switching from hardcopy subscriptions to checking articles for free online, and declining demographics also worked against newspaper companies since the early 2000s.

Between 2002 and 2007, the share price of The Times dropped 92%, from USD 51 to just USD 4.

In 2006, several angry, powerful shareholders began to lobby for change. The family shareholders resisted, famously using the dual-share structure to keep criticism at bay.

Source: The New York Times, 4 November 2006.

As ever so often, management hiding from shareholders doesn't work out well. By 2009, matters had deteriorated to a point that Vanity Fair was talking of "The New York Times on the precipice". The company was struggling to meet interest payments, and it had vast unfunded liabilities stemming from pension liabilities. A Mexican billionaire, Carlos Slim, had to be roped in to provide USD 250m of emergency funding. Slim became one of the company's bigger shareholders, which led to concerns that he could use the newspaper to pursue his personal agenda.

In retrospect, this crisis was the perfect moment to buy. Anyone who bought at that point has made more than 10x their money by now.

The turnaround didn't happen in a straight line, but sheer financial need made change come eventually. In charge of The Times since saving it from a near-bankruptcy experience in 1896, the Ochs-Sulzberger family implemented the needed measures.

A near-death experience catalysed overdue change

The shift in advertising from print to online happened faster than the newspaper industry had imagined. By 2010, Google alone earned more advertising income than all US newspapers combined. Shortly thereafter, Facebook also started to take a massive bite out of the US advertising industry's overall income.

The growing threat of being pushed out of business altogether finally got The Times to act:

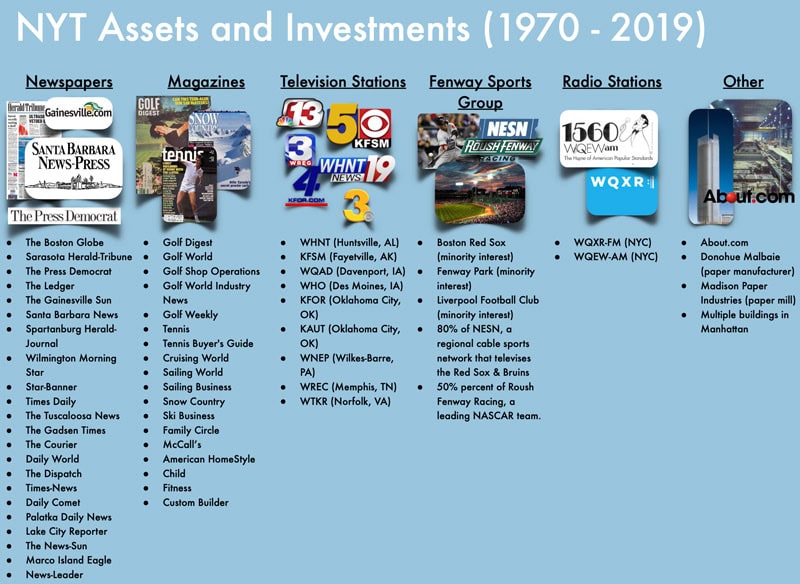

- Management sold off a hotchpotch of regional newspapers, television and radio stations, magazines, real estate, also-ran Internet companies and paper manufacturers that it had accumulated over the preceding decades.

Source: Mine Safety Disclosures, "The (Not Failing) New York Times" (2020).

- Using proceeds from these sales, the company reduced debt and unfunded pension liabilities.

- The Times invested into its tech platform. The remaining core team of journalists were directed to expend more effort on creating content that was suitable for an online audience.

- Using its existing readership, the company launched add-on products that generated additional revenue streams, such as subscription products for recipes and crossword puzzles.

By 2016, the stock price had recovered to USD 13. The worst seemed over.

Little did the newspaper team know that its worst nemesis and a set of renewed sector challenges were coming its way.

The era of "fake news"

2016 will go down in history as the year when large numbers of people in Western countries started to stage a revolt. Britain voted for Brexit, and in the US, Donald Trump became president.

Trump declared the mainstream media "the enemy of the people". He portrayed the leading newspaper of his home city as the worst case of journalists turning into political activists. He often tweeted about "the failing New York Times", predicting the paper to go out of business eventually.

Source: The New York Times, 17 February 2017.

Trump was wrong about the New York Times "failing", and his presidency even turned out to be a real bonanza for the newspaper industry. The Times managed to go from indebted to having net cash, thanks in no small part to the four years of increased news consumption during Trump's first term. The Times' share price went from USD 13 at the time of Trump's inauguration to USD 55 when he ran for a second time. It fell sharply when Biden was declared winner, also in anticipation that quieter times were ahead.

It hasn't really become much quieter, and one aspect highlighted by Trump has become a permanent part of the landscape.

The biased advocacy of "the news" is out in the open now – more than ever before. Mainstream newspapers and networks nowadays openly frame news to fit a political narrative, and everyone knows it:

- A former executive editor for The Washington Post released the results of interviews with over 75 media leaders and concluded that objectivity was now considered "reactionary and even harmful".

- The former The Times writer (and now Howard University journalism professor) Nikole Hannah-Jones is a leading voice for "advocacy journalism". Indeed, she has declared that "all journalism is activism".

- Stanford journalism professor Ted Glasser insisted that journalism needed to "free itself from this notion of objectivity to develop a sense of social justice".

At least, there is no pretending about it anymore.

On the one hand, this aspect is as old as the media industry itself. It's the choice of any media channel to choose its own bias. In fact, some argue that it's good business to have a bias. You may upset and alienate one half of the country, but you'll have the other half as a likely (and loyal) customer.

That's the optimistic interpretation of the situation.

There is also the concern, however, that excessive bias can irreversibly damage your reputation and make too many customers eventually turn their back.

Even steadfast loyalists of The Times will have found the last few years challenging, in terms of their beloved paper reporting one thing but reality undeniably turning out to be quite different.

Most recently, the Gray Lady portrayed Kamala Harris the leading contender in the election race. As it turned out, the country didn't just want Donald Trump, but it wanted him badly. The divergence between the mood of the country described by The Times and the actual voter preference was so starkly different that readers must be questioning why their trusted medium got it quite so wrong. If the self-described newspaper of record describes a fantasy world rather than reality, does it really justify paying a subscription fee?

The January 6 "insurrection" provides another powerful example. Matthew Rosenberg, the Pulitzer Prize-winning national-security correspondent of The Times, was recorded saying in private that "they [the left] were making too big a deal. They were making this into some organised thing that it wasn't." This was surprising, given that Rosenberg had authored or co-authored several articles in The Times that reinforced a version of the event that made it out to be another Pearl Harbor or 9/11.

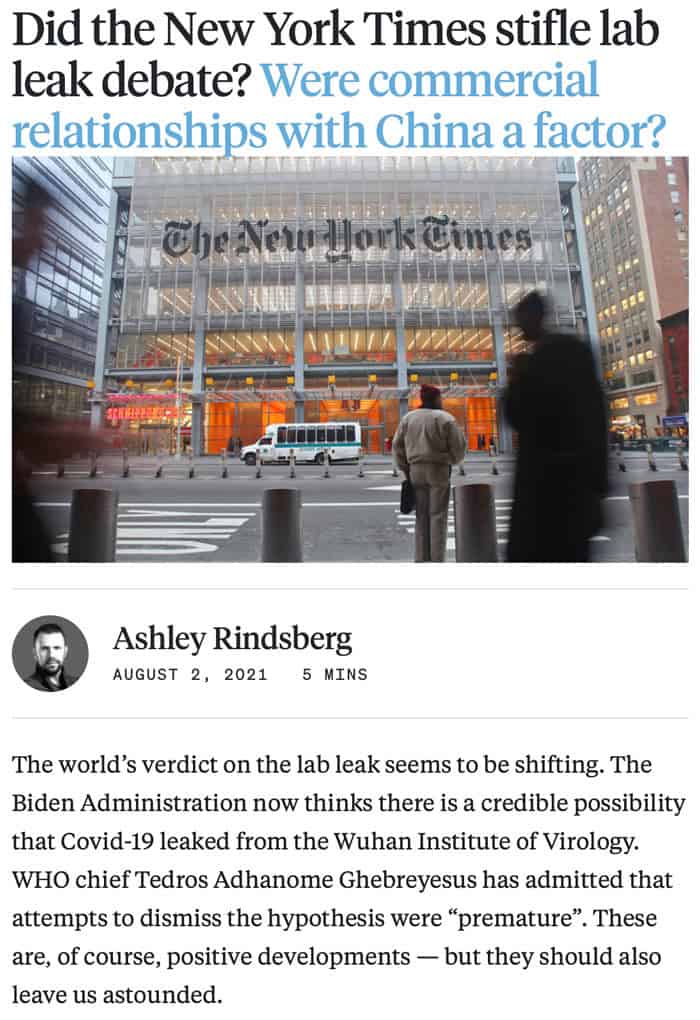

The pandemic brought to the fore how The Times was taking money from the Chinese communist government, which used the newspaper to disseminate messages through advertorials (ads that are designed to deceptively look like editorial). In 2020, The Times decided to scrub hundreds of these advertorials off its website. While this was legal – and other US newspapers were caught doing the same – it looked odd that a newspaper of The Times' standing not only agrees to print propaganda for a totalitarian government but then tries to hide what it had done (after all, the Times considers itself a living historical record, and meticulously maintains a searchable archive of articles that goes back further than the US Civil War).

For some, the revelation about the advertorials for the Chinese government put a new light on The Times reporting during the pandemic, which included claims that the Wuhan lab leak theory was "not plausible" and had "racist roots". Today, this theory is the widely accepted most likely scenario of what had happened. Did a cozy relationship with a tyrannical government that signed cheques to journalists influence how this spectacular case of creating a false picture came about? How many fervent readers of The Times will have been disappointed to learn that their primary source of information was potentially compromised by a murderous regime?

Source: UnHerd, 2 August 2021.

By now, it's fair to say that since 2016, the self-described newspaper of record has all too often joined hysterical antics that turned out to be false. Trust in the mainstream media is now at its ever-lowest, and many journalists have but themselves to blame for breeding so much of the public's suspicion.

Professional The Times journalists as chief arbiters of truth?

Believe that at your peril.

It can still be good business, though, and there may also be at least a degree of change ahead.

Are newspapers in for a collective rethink?

All of these developments had long been in the making. In fact, as far back as 1988, Noam Chomsky, the well-known media critique, predicted that such a showdown was going to happen. His book "Manufacturing Consent" is a "powerful assessment how the US mass media failed to provide the kind of information that we need to understand the world."

The optimist will say that, following the events of the last nine years and the recent US presidential election results, The Times' bias may now be due for a correction – at least to some degree.

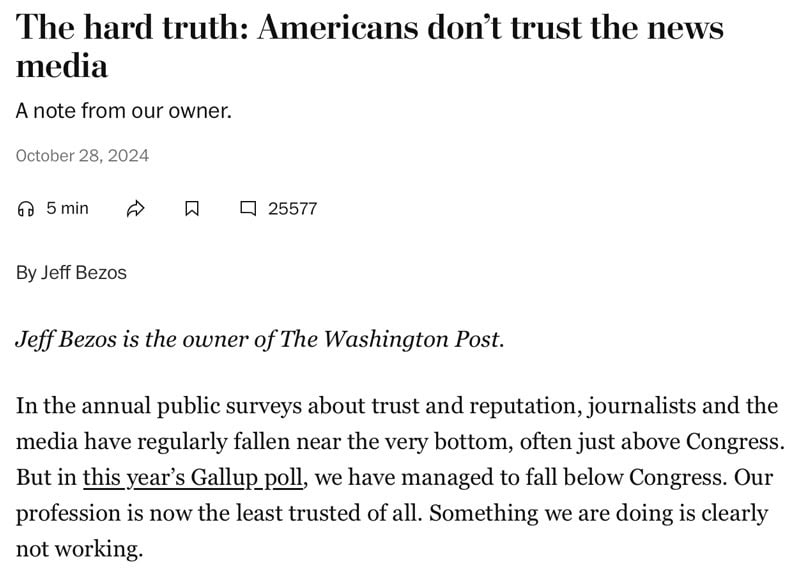

President-elect Donald Trump won overwhelmingly, despite The Times and just about any other mainstream media outlet doing much to support the other candidate. For the mainstream media, this has now led to a moment of genuine self-reflection.

Some outlets are now openly rethinking their strategies. Jeff Bezos, owner of the The Washington Post, did so even ahead of the election by refusing to endorse Kamala Harris as candidate, despite opposition from editorial staff. In an op-ed, Bezos claimed that the legacy media may have at least partly to blame themselves for the loss of public trust, and he called for the newspaper to address the issue that its reporting was too biased.

Source: The Washington Post, 28 October 2024.

There have been other recent cases of business leaders engaging in hard-hitting self-critique. In a letter to the US government, Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Meta/Facebook, "regretted" bowing to pressure from the Biden administration to censor "certain Covid-19 content". Tech billionaire Patrick Soon-Shiong, who owns the LA Times, made an editorial board appointment specifically geared towards "creating some level of balance".

Source: Financial Times, 8 December 2024.

The Times has yet to undertake such a step, but it will be under pressure to do something.

According to Elon Musk, "citizen journalism" through platforms like X and Substack is the way forward for media. Indeed, Mediaite just crowned Musk and podcaster Joe Rogan the #1 and #2 "Most Influential in News Media 2024", in a clear sign that alternative media is on the rise. Some believe that these newer forms of journalism will kill off the mainstream media altogether. However, it seems more likely that it will turn out to be the corrective force that the mainstream media needed to get back on a better track and regain some trust. In fact, Musk said as much himself in a 2022 tweet: "Mainstream media will thrive, but increased competition from citizens will cause them to be more accurate, as their oligopoly of information is disrupted."

The Mainstream media aren't dead, and the changing market conditions won't kill them.

They are simply evolving – and not for the first time.

The Times has been adapting to changing conditions for decades, and it's likely to do so once more.

The incredibly growing digital subscriber business

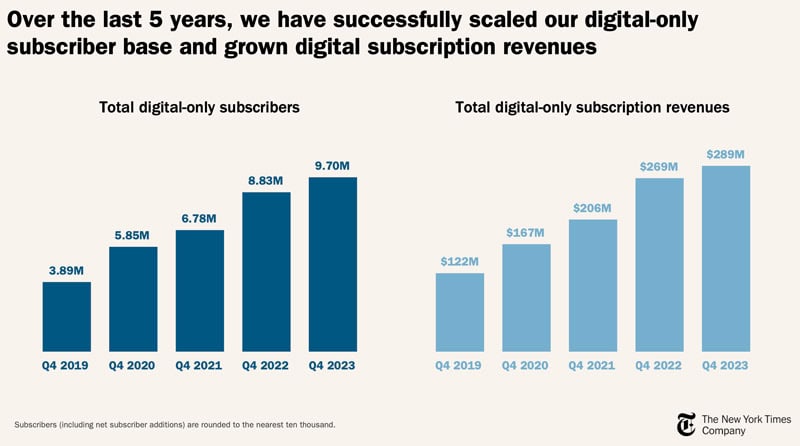

Amid all the criticism that The Times has faced over the past years, it has built a digital readership that is bigger than that of The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post and the 220 local newspapers owned by Gannett *combined*.

Digital revenue represents a higher margin and higher return on capital business when compared to the capital and manpower intensity of printing and distributing physical newspapers. With that in mind, it's no surprise that The Times stock is up multiples times despite the company going through turbulent times.

In the six weeks since the US presidential election, the stock has been losing some ground. Besides volatility in markets, there were some specific worries about the fallout of the election result. According to hedge fund investor Bill Ackman, "half of America woke up to the reality that they have been manipulated by the media. This should lead to an abandonment by many of the MSM as their primary source of information.” (The entire X-thread linked to above is worth reading.)

Indeed, *some* subscribers of The Times will have voted with their feet by now.

Does it matter, though?

The election result could lead to some corrective measures by the dejected media, which could bring a new audience that is larger than those who left.

Also, the upcoming Trump term could lead to another cycle of increased news consumption.

Last but not least, all of this may be overridden by one key aspect: The Times is the one media company which has figured out how to take a legacy media brand to the digital realm and make loads of money off subscription fees. In this regard, it is without equal in the world.

Even at the very peak of its print era success, The Times "only" had 1.6m readers. Today, it has 11m digital-only subscribers who pay money to read the paper. That's nearly 7x the number of print subscribers it had at its peak. In comparison, The Washington Post currently has 2.5m digital subscribers, which equals just 3x the number of print subscribers it had at the turn of the millennium. For The Wall Street Journal, it's 3.4m digital subscribers compared to previously 1.8m print subscribers, a mere 2x.

Source: The New York Times Company, Fourth Quarter and Full-Year 2023 Earnings Presentation.

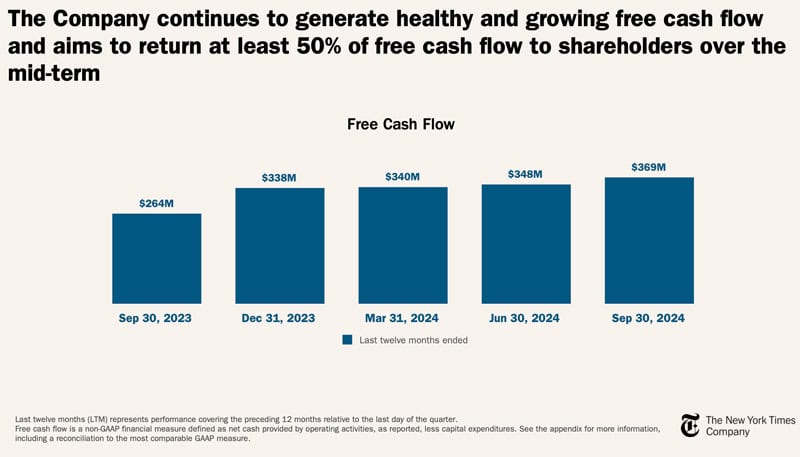

The Times is debt-free, has plenty of cash and generates a high return on its shareholders equity. It can afford to employ an entire army of journalists (1,700, up from 1,200 in 2010), and it even pays them well. It may have lost some of its best-known journalists to platforms like Substack, but many journalists still prefer to work for a place with the gravitas and access of a brand like The Times.

After hiring a lot of talent from firms like Google, Facebook and Spotify, The Times now has an unrivalled digital platform and internal operations. It is quite probably the technologically most advanced newspaper publisher in the world. Its website and app are best-in-class, and filled with beautiful charts, graphics, photos, videos, and visualisations.

With its new focus on digital, The Times has long broken free from its old rule book. E.g., gone are the times when the paper released its major breaking stories in the evening. In line with online news consumption patterns, these are now released during the morning, when online audiences are at their peak.

Its print subscribers still contribute a disproportionately large percentage to overall revenue, because subscribing to the print edition costs significantly more. However, the base of print subscribers is shrinking, and print revenue is inherently less profitable. At some point, the print issue may even be abolished altogether.

The Times also successfully converted from an advertisement-first business to subscription-first. Around 2000, it would have made 68% of its revenue from advertising and only 25% from subscription fees. In 2023, subscription fees contributed 67% of group revenue, and advertisements are down to 23%. The company now generates revenue from producing a form of journalism that millions of people in the US and elsewhere are willing to pay for, which is a stark reversal from the days when advertisement had to subsidise journalism. Say of The Times' advocacy journalism what you like, it has not stood in the way of building highly profitable and scalable business – and shareholders profit, too.

Source: The New York Times Company, Third Quarter 2024 Earnings Presentation.

Will The Times go truly global?

How many more subscribers could The Times win over the coming years?

The growth of its digital subscriber business is a fairly recent phenomenon. A proper paywall – for anyone who wanted to read more than a handful of articles per month – was not introduced until 2011. That year ended with 0.4m digital subscribers, and it took until 2015 to get to the 1m subscriber milestone. Signing up the second million then only took a year. Between 2015 and today, The Times has on average signed up a million new subscribers per year. While there were inevitable fluctuations, it's fair to say that the company truly understands acquisition, engagement, and retention of paying subscribers.

As with any digital subscription business, after a certain break-even point, revenue from incremental subscribers becomes highly profitable.

In February 2019, the company set itself the target of reaching 10m subscribers by 2025. Why 10m? Management thought this represented 10% of the total addressable market, comprising people who are English-speaking, college-educated, left-leaning, probably a bit older, and interested in US news.

To broaden its appeal, The Times has opened additional international bureaus. International subscriptions have climbed to about 21%. Within the US, geographic reach is now also less limited to the city that provided the paper's name than it used to be.

Will The Times turn out to be the one US newspaper that becomes a truly global publication? Could this now be driven by the world's growing fascination with US exceptionalism and an equally growing need for non-US readers to stay on top of what's happening in the world's leading economy?

One former CEO of the company believes it could get to 30m readers. Some investors share this sentiment, and not only since yesterday.

In 2022, activist investor ValueAct Capital bought a 7% stake and rallied for putting yet more emphasis on building the subscription basis. The fund believed that The Times' digital activities were "in the early innings of penetrating a large, addressable market, can sustainably increase their customer lifetime value, are already solidly profitable, and have a much more attractive competitive environment."

The same argument still stands today. Could the management now switch to dreaming even bigger than it did in the past?

The company had previously upped its goal, wanting to reach 15m subscribers by 2027. This seems ambitious but achievable. Could the second Trump term turn out as advantageous for the Gray Lady as the first one? Might The Times change in a way that will make the paper more attractive to a larger percentage of the American population?

Who knows, it might even be the one newspaper that manages to transform itself into a digital news resource for the entire world. In an extensive research report published in 2020, Morgan Stanley set out that The Times had the unique opportunity to become a "global premium news brand" with a total addressable market of up to 100m readers worldwide. It also pointed towards its pricing power, which for publications like The Times tends to be significant.

The media industry is complex, and it's undergoing a multitude of challenges (for a quick overview, check out the Visual Capitalist infographic "33 Problems With Media in One Chart").

There is also the subject of AI, which is bound to have massive reverberations for the news business and the media industry as a whole. It could turn out the most beneficial thing that has ever happened to the industry, or it could destroy it – no one knows.

Source: Poynter, 8 May 2024.

The stock of The Times is not particularly undervalued (see estimates below), but it could turn out to be one of those stocks that never become cheap in absolute terms because existing revenue streams are secure, and the future upside is just so large.

Source: Morgan Stanley, 5 November 2024.

Short term, the stock is as difficult to make a prediction about as every other stock. Longer term, I wouldn't be surprised if the company surprised on the upside. This could take place in a combination of:

- Management adjusting to the new reality of the mainstream media and rethinking its bias in such a way that its total addressable market grows.

- Evolving from a US brand to a global brand.

- Utilising a combination of cross-selling and pricing power to achieve a level of profitability that goes beyond the conventional scalability of the digital subscription business.

Trump inoculated the American public against the bias of the news, and that entire part of the story is now likely going to disappear in the rear mirror. The Gray Lady is more likely to remain "prevailing" rather than "failing". Trump got this one wrong, but he may now provide another "Trump Bump" bonanza for the news industry. If worries about AI can be overcome, this stock may hit new highs sooner than expected.

Dominant, fast-growing tech play in emerging markets

Looking to buy a fast-growing, world-class tech company at a fraction of US valuations?

The company featured in my latest research report hails from a small and exotic country, but it does not need to hide behind US tech firms such as Google, Apple or Amazon.

With a #1 market share in several sectors, off-the-charts financial metrics, and continuous high-paced growth, it offers 5x upside potential over the next 3-5 years.

Dominant, fast-growing tech play in emerging markets

Looking to buy a fast-growing, world-class tech company at a fraction of US valuations?

The company featured in my latest research report hails from a small and exotic country, but it does not need to hide behind US tech firms such as Google, Apple or Amazon.

With a #1 market share in several sectors, off-the-charts financial metrics, and continuous high-paced growth, it offers 5x upside potential over the next 3-5 years.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post: