He bought his first stocks while still at school. Using a modest inheritance of 3,200 Deutschmarks, Ehlerding managed to become a millionaire through investing at the age of 25. Later, he became a multi-billionaire. In the 2000s, his publicly listed holding company, WCM, suffered insolvency, but Ehlerding returned as wealthy investor, active real estate developer, and major philanthropist. Throughout his entire life, he was primarily a full-time investor in publicly listed stocks. That's over 60 years of stock market experience to look back on!

On 25 July 2022, the son of a wholesale trader of shrimps from Bremerhaven on Germany's North Sea coast will celebrate his 80th birthday.

Having chosen to largely stay out of the limelight during the past decade, Ehlerding is less known among the younger generation of investors. Even though he barely speaks to the media nowadays, Ehlerding granted Undervalued-Shares.com a two-hour interview in June 2022 where he gave away a lot of personal details. The Hamburg-based investor freely shared his advice for the next generation of investors, and spilled the beans on the investments that he is currently interested in (including Volkswagen and Porsche, which Undervalued-Shares.com Members will be well familiar with – though our overlapping interests are coincidental).

In "The world's best investors", Undervalued-Shares.com will feature three very successful equity investors about whom little or no up-to-date information can be found in other sources. The entertaining personal stories of these three stock market professionals are intended to help readers learn from their individual experiences and gain inspiration - including one or the other current investment idea.

As an exception, the interview with Karl Ehlerding is published in two languages (German and English).

Swen Lorenz: Mr Ehlerding, on the back of your work, I landed some of my first successful investments in the 1990s. Many other members of my generation built their initial wealth following you into specific investments. However, your very first steps on the stock market date back much longer. How did you start your career?

Karl Ehlerding: It all began with the privatisation of Volkswagen in 1961. Shares of VW were offered to the general public for a price of DM 350 (Deutschmarks) each. People of lower income, however, were able to subscribe to the shares for a discounted price of DM 280. Students and pupils could even get them for DM 210. However, everyone was limited to subscribing to just five shares.

At the time, I was a pupil at the commercial high school of Bremerhaven. I told my fellow students of the upcoming IPO and of the opportunity to subscribe to shares for a discounted price if you were still at school. We were 28 in my class, but only two of my fellow classmates wanted to subscribe to the IPO.

I went to my local bank and said: "Please give me the forms for the IPO." They gave me one form. I said: "No, I need 27!"

Then I entered the names of all my fellow classmates and went back to school. "Please, sign here", I told everyone. In the end, I got nearly 100 shares for a price of DM 210 each.

The stock's first price following the listing was DM 980. At its peak, the second price was DM 1,030 even. The stock went up to DM 1,200. It had been entirely clear to me that the stock was going to do well, because everyone knew and liked the product, the Beetle car. BILD, the largest German daily newspaper, wrote: "Even God is buying shares in Volkswagen".

In the end I sold at a price of DM 880. At the time, if you held on to a stock for more than three months, all capital gains were tax free. I didn't sell at the peak, but one hardly ever catches the moment a stock peaks. Buying at the highest point is mere luck. In any case, I had gotten off to a good start.

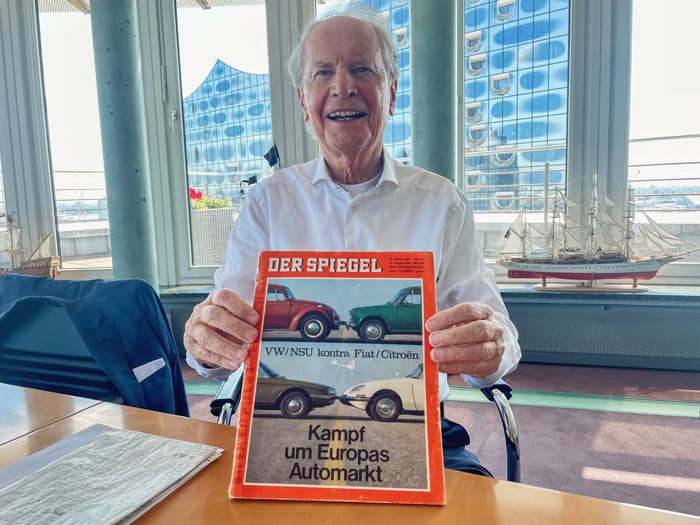

Karl Ehlerding with a 1969 issue of Germany's DER SPIEGEL magazine.

SL: How did it continue from there, and did you develop your own investment style?

KE: My investment style primarily consisted of "learning by doing".

Following my transaction with Volkswagen stock in 1961, I started to attend university in Hamburg. At the university, I finally had all the major German newspapers at my disposal. I spent much of my time reading.

To become a good investor, three aspects are key.

You have to be good at calculus; ideally, you have to be able to work out figures in your head, which then also comes in handy during negotiations.

Secondly, you have to be good at using logic.

Last but not least, you need common sense. You need to sense-check your investment ideas and look at it all from a bit of a distance. Does it all stack up?

SL: How did things continue for Karl Ehlerding as a student?

KE: During my time at university, I made an investment in a regional railway company. This was one of my "aha" moments. The company in question was called Hildesheim-Peiner Kreis-Eisenbahn; as the name implies, it operated a railway track between the cities of Hildesheim and Peine.

The legal predecessor of what is today's German business daily Handelsblatt reported about the railway company: "The cargo business is declining, the route between Hildesheim and Peine will be closed down, and the company will go into liquidation."

Checking the specialist German stock market newspaper, Börsen-Zeitung, I noticed the stock was trading for DM 36, even though its nominal value was DM 300. This piqued my interest. The way balance sheets are structured, you'd have expected that a liquidation would yield at least the nominal value of the share.

I went to the university's basement to check the archival copies of Hoppenstedt, the annual German guide book to all companies listed on the exchange. At the time, even a tiny regional railway company was dedicated five pages of information in this guide book. The list of assets was broken down in great detail, listing every single shed. I added up all the figures and concluded that, indeed, a liquidation would yield DM 300 per share. My first reaction was: "No, that cannot be, where did I get my analysis wrong?" After all, we are taught to believe what's printed in newspapers.

However, the liquidation was going to yield a lot more than DM 36 per share.

During the entire period of the company going through liquidation, I bought more stock. At the time I was 22, 23 years old. I bought as much as I could get hold of.

At the end of the liquidation, shareholders were paid a liquidation dividend of DM 530 per share. This gave my fortune a massive boost!

In 1968, Germany's DER SPIEGEL magazine published an article about Ehlerding (right) leading a group of investors at university.

SL: Did you also hold onto other investments for multi-year periods? Is this a part of your strategy, and would you say that being patient is key to successful investing?

KE: Yes, you do occasionally need to hold onto an investment for half a year or maybe five years. This can actually be part of the fun, if you choose the right investments.

SL: Did a young Karl Ehlerding have a mentor or idols?

KE: At university, I was lucky to have a truly outstanding professor for business economics. Professor Johannes Fettel taught me everything about valuations and liquidations, and he also taught me about taxes. He taught me a lot. To be clear, without attending university first, it would have been difficult to pursue the career that I pursued. The theoretical knowledge that I gained at university was very valuable indeed.

SL: Thanks to your theoretical knowledge, you landed quite a few real investment coups. What was the highest percentage gain of your investment career?

KE: In terms of multiplying my investment, it was clearly the Solnhofer Aktien-Verein, a company that produced stone slabs. At the time, I noticed that the stock was trading for DM 60, even though its nominal value was DM 100. Once again, I took a very basic piece of financial information as indicator that it was worth taking a closer look.

I went back to the university's basement to look at the available archival material.

The company had a market cap of DM 300,000, i.e. it was a real micro-cap. In the archival material, I spotted that it owned no less than 3.2m square metres (790 acres) of land in a particularly beautiful part of Germany, the Altmühltal. The company had DM 3-4m in annual sales.

Thanks to its beautiful location, it was also operating a restaurant that catered to day-trippers from Munich.

Additionally, it owned 20 or 30 apartments.

Last but not least, it also owned a museum. During its production of natural stone slabs, it often came across valuable fossils of fish. The museum's exhibits were a valuable, albeit overlooked asset.

I figured that something wasn't quite right. Indeed, the people who were selling their stock for just DM 60 weren't quite right in their heads!

To complete my assessment, I went on a visit to the company's facilities and looked at everything. Anonymously, at that point.

Then I started buying, very carefully and across multiple years. While I purchased stock, the price went from DM 60 to DM 70, DM 200 and then DM 300. I was buying the entire time.

Once I owned 20% of the company, my colleague Klaus Hahn and I introduced ourselves. We also went for a hike around the company's massive piece of land. While hiking, we noticed a constant humming sound in the distance. It was only then that we realised another company was producing cement nearby.

Following our visit, we subscribed to the local newspaper and learned that the local cement manufacturer experienced booming business. At the time, the German government was building the canal connecting the rivers Rhine, Main, and Danube. You need incredibly large amounts of cement to construct such a canal. The neighbouring cement company, the Solnhofer Portland-Zementwerke, was running out of raw material for producing enough cement. That's why they became keen on their neighbouring producer of stone slabs. The massive land owned by the stone slab producer contained raw material for producing cement.

Sometime later, we sold all of our shares to the neighbouring cement manufacturer for a price of DM 5,000.

Every single company I've ever invested in, I kept following after I had sold my shares. In the end, the remaining shareholders of the stone slab producer received a tender offer of EUR 12,300, which was equivalent to DM 24,600.

SL: You already mentioned your business partner, Klaus Hahn. Warren Buffett has got Charlie Munger at his side, and I believe that you've also worked closely with several allies. What did your career teach you about forming a successful investment team? Or would you say it's preferable to be a lone wolf?

KE: When it comes to generating ideas, I am definitely working just by myself.

However, to take bigger transactions to a successful conclusion, you need to delegate. It's impossible to do it all by yourself.

To pull off major, successful investments, you need to be good at delegating. Having the necessary skills for delegating is extremely important.

SL: During the 1990s, when I myself was visiting shareholder meetings while still a high school student, you invested in an entire range of residential property companies. You purchased large stakes and actively influenced their management. These investments temporarily got you to a net worth of five billion euros. Can you tell us more about these transactions?

KE: During my research, I came across residential property companies that had a quasi-charitable mandate. These were hybrid structures – listed on the stock market as companies, but tied to the greater good through regulation in their statutes.

I worked out the value of the underlying assets of these companies. During the 1980s, buying shares in these companies was akin to buying residential property for just DM 150 per square metre – a ridiculously low price. Because of their hybrid status, investors didn't want to pay the full value of the underlying assets. E.g., some companies had in their statutes that in the case of a liquidation, shareholders would only receive the nominal value per share, and any sales proceeds above that would be donated to the Red Cross.

I invested regardless because I anticipated a change in regulations. During the 1980s, the tax privileges that these companies enjoyed were ended by the government, and regulation was introduced to gradually turn these companies into "normal companies".

It was clear to me that this was a huge opportunity, and I focussed my efforts on three such companies that existed in the medium-sized city of Gladbach. To pursue these investments, I didn't just subscribe to the city's local newspaper, but I actually moved there for half a year. Meeting with local shareholders, I tried to buy as many shares as I could. I remember sitting on the sofa of a retired director of the local savings and loan bank, whose shares I wanted to buy. The stock was trading for DM 120 at the time, and I offered him DM 1,000 because I knew the underlying asset value was DM 4,000. He told me: "Mr Ehlerding, you are offering way too high a price, don't be so stupid!"

In the end, we managed to buy 100% of the shares of all three charitable residential property companies in Gladbach. Subsequently, I found a structure that enabled us to realise the underlying asset value without paying capital gains tax – this was a unique achievement on top of everything else. In terms of the absolute amounts involved, this was the largest set of transactions of my life. In the end, the publicly listed holding company that I controlled at the time, WCM, owned 80,000 apartments. The company became worth billions of euros thanks mainly to these particular transactions.

SL: The outward perception is that you managed to make use of inefficient markets, and that you've done so for decades before the rise of the Internet. However, nowadays it's hardly possible to gain an edge by looking up archival material at universities. In the day and age of the Internet, all information is available at the touch of a button and all information is immediately priced in – or at least, such is the common perception. Given your decades of experience with markets and how they've changed with the rise of computers and global institutional investors, do you think private investors still have a chance to gain an edge and beat the markets?

KE: There are always opportunities in public markets. Take the example of Porsche Holding SE, the publicly listed holding company of the Porsche family.

Porsche Holding (ISIN DE000PAH0038, DE:PAH) consists solely of equity, i.e. it has zero debt. Its biggest asset is a 53% voting stake in Volkswagen (voting share ISIN DE0007664005, DE:VOW). If you purchase two shares of Porsche Holding, you indirectly own one voting share of Volkswagen. It's easy to figure out that the stock price of Porsche Holding should really be trading at twice what it is trading for today.

However, there is more to it. The market cap of Volkswagen is currently just EUR 80bn. This includes a 100% stake in Porsche AG, the company that produces the Porsche sports cars. Volkswagen is valuing its stake in Porsche AG at just EUR 12bn. In comparison, Ferrari (ISIN NL0011585146, NYSE:RACE) has a market cap of EUR 35bn, even though it produces just a tenth the number of cars as Porsche. This will become more apparent once Volkswagen launches the planned spin-off and IPO of Porsche AG.

You also need to compare Volkswagen to Toyota Motor (ISIN JP3633400001, JP:7203). Toyota doesn't own a crown jewel of the kind that Volkswagen owns with Porsche AG. It's much more of a mass producer. If you deduct the value of Porsche AG from the market cap of Volkswagen, then you conclude that Volkswagen is currently valued at just EUR 10bn, 20bn or 30bn. Toyota is about the same size as Volkswagen, but it has a market cap of EUR 240bn.

Volkswagen has a large hidden reserve.

All of this will become more widely known once Porsche AG gets listed on the stock market. It will be reported in every single major newspaper, which will draw attention to it. It's all very simple, anyone can do the math.

However, it gets even better. Dr. Hans Michel Piëch is the largest owner of voting shares in Porsche Holding. All outstanding voting stock of Porsche Holding are worth just EUR 10bn at today's price. Put another way, for just EUR 5bn, you could theoretically buy control of Porsche Holding, which in turn gives you control over Volkswagen. For just EUR 5bn, you get to control a company with EUR 250bn in annual sales, 670,000 employees, and 160 factories.

What if someone offered Dr. Hans Michel Piëch an additional EUR 10bn for his voting shares in Porsche Holding? Would he be tempted? For EUR 15bn, you would then get control of Volkswagen. This would give the stock of Porsche Holding a value of EUR 196 per share, or twice what it is currently trading for on the stock exchange.

I have bought stock in Porsche Holding for prices of EUR 70, EUR 80, and EUR 88. I recently bought more for a price of EUR 68. Porsche AG currently has problems in China, but this will prove temporary. At some point, the market will realise that Porsche Holding has a much higher underlying value.

I have now been invested in Porsche Holding for a year. It's fine by me if I have to stay invested another one, two or three years. After all, I am being paid to wait. Porsche Holding is paying my family a dividend yield of 4.25% per annum.

Porsche AG is a world-class company with great products. Once they do their IPO, the company will probably enter Formula 1. This makes for a very interesting constellation.

When I first began investing, I started with Volkswagen. Now, I have come back to Volkswagen. 60 years later, it's gone full circle!

SL: I noticed that you almost exclusively focussed on investing in Germany. What's the reason?

KE: There are so many opportunities in Germany, I simply never had to look abroad to find new investment ideas.

SL: Your entire life, you've focussed on nothing but publicly listed companies, right?

KE: Indeed, I never invested in start-ups or private equity. I prefer publicly listed companies, and they need to have a higher underlying value than what I am paying.

I want to buy existing assets on the cheap. I am a value investor.

The reasons are always different.

E.g., the market may have simply forgotten about a particular company.

It may be a company that got itself into a difficult spot.

Or it's a company that ended up in Chapter 11-style insolvency. That's what had happened in the case of Klöckner & Co. (ISIN DE000KC01000, DE:KCO), a company where I bought a major stake in the past to benefit from its financial restructuring.

Last but far from least, I like buying into companies that have unused tax losses. You can make use of them to have the company operate tax-free once it has turned around.

I have never, ever liquidated a company. Each time I invested and got control, I kept the company going. If we closed down an existing business, then we made sure to find a new business to make use of the remaining listed shell company. Sometimes we brought new partners onboard, sometimes we stayed invested.

SL: You are well known to be a buyer when no one else dares to buy. Outside of the stock market, the example I can think of is your legendary land purchase in Mallorca, Spain. What happened there?

KE: I have the great luck of owning one of the ten largest fincas on the Spanish island of Mallorca.

It all dates back to a failed hotel project. Someone had tried to get a hotel off the ground on the island's east coast, which back then was not popular. They tried to do something on an ambitious scale. However, it all ended in bankruptcy and it fell into the lap of a bank, the Banco Exterior de España, or "BEX".

I received a call from an agent: "Mr Ehlerding, I've got something for you, but it's fairly large. It's 4m square metres (988 acres), with four bays. It's supposed to be divided into seven smaller units."

I replied: "I want the entire thing, but I will only buy if I get a discount."

The price negotiations took more than half a year. At that time, the bank had already owned it for 20 years.

In the end, I got them to agree to a price of 300m Spanish pesetas. Back then, 100 pesetas was DM 1.20. For DM 3.6m (today: EUR 1.8m, USD 1.8m), I got 4m square metres. I didn't even have to pay property transaction tax, because the land was held by a Spanish limited company. If you sold shares in a company, then no property transaction tax was due at the time.

Following the purchase, I told my wife: "Right, now we should go and take a look at it!"

We moved into the finca 28 years ago. My wife, Ingrid, and I have revitalised the land. We are rearing sheep and growing almonds.

This purchase, too, was a great value investment.

SL: Such success stories should inspire private investors to spend more time pursuing contrarian investments. However, Germans, in particular, are not keen on investing in equities or even taking any form of active interest in investing at all. Why do you think that is?

KE: That is indeed the case, Germans are not a nation of equity owners. During corona, we saw 2m or 3m new brokerage accounts opened. However, compared to other countries, Germany is still lagging in terms of equity culture. This goes back to the two world wars and the resulting periods of inflation and currency reform, when people lost everything. There is a collective shock that sits deep in the DNA of the people.

SL: What is your advice to the next generation?

KE: Just as it has always been, the stock market is a great place for young people to start their career. Private investors can still gain an edge in the market, and you don't need to do more than carefully read what is available in public sources such as newspapers.

A university degree in business economics provides you with a solid basis.

SL: How does your day-to-day investing work look like?

KE: Each morning, I first read the national German newspapers, Die Welt and FAZ, as well as my local newspaper, Hamburger Abendblatt.

Once I am done with it, we split the FAZ between my family. One half of it goes to my son, who lives next door. The other half goes to my wife, who primarily reads the Feuilleton as well as nature and science. I mark important articles and send copies to associates.

Before I do any of that, I go for a run in the nearby forest. My family have breakfast together. Then I drive to the office, or to be more precise, I get driven to the office. Having a driver is the best investment you could treat yourself to. I read in the car, or I make phone calls. The amount of time I save by being able to utilise the time I have in the car pays for the driver ten times over. Imagine how much time this has saved me over the course of 30 years!

Each day, I read twelve newspapers. My investment work is all about reading.

SL: Based on your copious reading, which stocks are you currently keeping an eye on?

KE: I was heavily invested in K+S (ISIN DE000KSAG888, DE:KSA), the producer of fertiliser. I bought at EUR 8, sold at EUR 36, and it's now back at EUR 28. K+S is worth keeping an eye on.

Freenet (ISIN DE000A0Z2ZZ5, DE:FNTN) is a great stock because of its tax-free dividend. The stock is trading at EUR 23. Each year, you get a tax-free dividend of EUR 1.60 per share.

Elbstein (ISIN DE000A1YDGT7, DE:EBS) is a real estate developer I am invested in. The company has tax losses, a lot of undeveloped land, and cash.

ERWE (ISIN DE000A1X3WX6, DE:ERWE) is a work-in-progress kind of investment. It's a real estate company with projects in major cities.

I own 12% of MATERNUS-Kliniken (ISIN DE0006044001, DE:MAK), a clinic operator that has 3,000 beds. The company is supposed to be sold at some point.

SL: What about your family foundation?

KE: Our family foundation will have equity of EUR 25m at year-end 2022. Our "Ehlerding-Foundation" funds charitable work for students and young people, using the motto "Ensuring that your life is a success". Over the past 25 years, we have touched the lives of 57,000 young people.

We have also purchased the old school building where my wife Ingrid and I studied in the 1950s. We received a call that the school needed help. We bought the building, and we recently invested EUR 11m in extending the facility.

SL: Besides the stock market, which other interests and passions do you pursue nowadays?

KE: My number one hobby is hiking. I love visiting the Lüneburg Heath near Hamburg, the Harz highland area in northern Germany, and Tyrol.

My second hobby is Kyrgyzstan, the mountainous landlocked country in Central Asia. During the 1990s, I helped fund a brewery in the country, which made me become its honorary consul in Hamburg. Just the other day, I received an email from an advisor to the president of the country, who wrote: "… without a doubt, you are our best honorary consul in Germany". Each New Year's, I invite all the Kirghiz of the Hamburg region to a party. This is a lot of fun!

Karl Ehlerding with the flag of Kyrgyzstan, which he represents as honorary consul in Hamburg.

SL: You are now looking back at more than 60 years of investing in equities. Few people have had the good fortune of getting to spend so many decades doing nothing but investing in public markets. With all this experience, what is the most important piece of advice you would like to give to my readers?

KE: The worst thing you could do is to lose focus.

You also shouldn't get too nervous about your investments too quickly. It usually doesn't pay to buy and sell too hastily. You have to stick to something.

Finally, always make the effort to go and personally check out what you have invested in.

SL: Mr Ehlerding, many thanks for the insights into your inspiring life and the advice on how to become a successful private investor. On behalf of everyone who reads this interview, I am wishing you a wonderful 80th birthday with your family.

Karl Ehlerding works in a penthouse office overlooking Hamburg's newly-built philharmonic hall. He had become the building's first tenant over 25 years ago when the city's harbour region experienced its first wave of regeneration following decades of decline, and he now occupies one of the finest offices in the city. From his office balcony, Ehlerding has a panoramic view of the never-ending comings and goings of the vast Hamburg harbour. The day I visited to conduct the interview, the MS Queen Mary II was visiting, too. The self-proclaimed fitness fanatic and vegetarian was in top shape and jumped about his office with a level of energy that would put many 25-year-olds to shame. Undervalued-Shares.com hugely enjoyed picking Karl Ehlerding's brain. In addition to his 80th birthday at his finca in Mallorca, Ehlerding and his wife Ingrid will also celebrate their 50thwedding anniversary – the Golden Jubilee – in September 2022.

Next week: the second part of "The world's best investors" will analyse the approach of someone who would be one of the absolute superstars of the investment industry – if only he wasn't so reclusive that barely anyone has ever come across him. Undervalued-Shares.com has collected the sparse available source material for over 20 years.

Blog series: The world's best investors

There's more to "The world's best investors" than this Weekly Dispatch. Check out my other articles of this three-part blog series.

Benefitting from a Swiss banking renaissance

A historically low p/e of 8.

A dividend yield of >6%.

Large-scale buy-backs.

Meet the Swiss banking stock that currently offers the best buying opportunity since the Great Financial Crisis.

Benefitting from a Swiss banking renaissance

A historically low p/e of 8.

A dividend yield of >6%.

Large-scale buy-backs.

Meet the Swiss banking stock that currently offers the best buying opportunity since the Great Financial Crisis.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post: