For years, I have been trying to find a copy of an ultra-rare book published in 2008.

It told the inside story of a few mining entrepreneurs who built a company from zero and sold it for a staggering USD 2,500,000,000 (2.5 BILLION) in cash just 674 days later. That's a quick fortune earned, if ever there was one!

The company was listed on the stock market, and public investors were taken along for some of the ride. In 2006/07, this was the single best British company to own stock of.

Somehow, though, the company's insiders seem to have regretted publishing their detailed account. The book strangely disappeared from the market shortly after it was published. Curiously, there is ample evidence that an active effort was made to erase the book from history.

Always eager to learn from other peoples' investment success, I badly wanted to read it. All the more since its mysterious disappearance! What was the magic sauce that made this company – and its publicly listed stock – take off like the proverbial rocket? I figured that some of my readers, too, would be interested in its key lessons.

Finally, I managed to get my paws onto a copy!

Disappeared and secret it is no more.

Here is a 4-point overview of what I learned from this precious gem of stock market history, and how these lessons continue to apply to investing today.

Finding the rare winner among bags of losers

The book in question is "UraMin – A team enriched. How to build a junior uranium mining company".

Junior mines are companies that are still looking for resources, rather than producing the resource. As most of my readers will know, they are among the most speculative ventures one can invest in. About 99% of them make most investors lose their entire investment. The remaining 1% regularly end up making investors 10, 20, or even 100 times their money.

UraMin was primarily the brainchild of Stephen Dattels, a Canadian mining entrepreneur with a decade-long track record. The book describes the genesis of UraMin from his own perspective and that of his two partners, Ian Stalker and Neil Herbert. It was, for all intents and purposes, a real insiders' account of the incredible success story.

UraMin produced oodles of capital gains. It was a lucrative investment not just for its pre-IPO investors, but also for those who bought into it through shares acquired on the open market post-IPO.

I once made handsome profits off an exploration company, but I don't consider myself an expert on the subject. What I am interested in, however, is the art and science of finding investments that can make investors many times their money. I am looking for those across all sectors and industries.

Finally, I got to read Dattels' account of building UraMin. I did so to find factors that I will consider when analysing other companies with similarly good prospects for investors.

Here is what I found.

1. Invest when there is a dichotomy between market pessimism and fundamentals

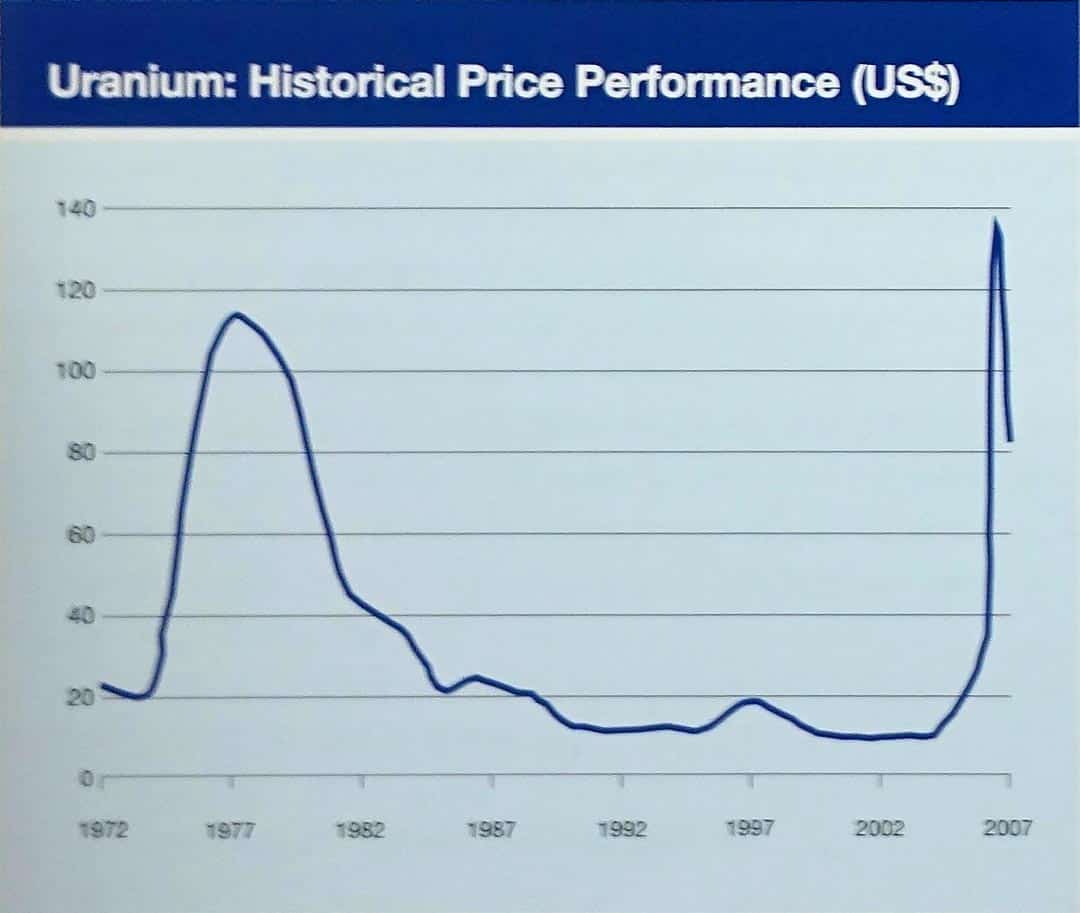

It's no surprise that the book starts with describing just how "Down and Out" the market for uranium-related investments was at the time.

At the turn of 2004/05, you would have been hard-pressed to find any investors interested in uranium. The price for the metal had been in a 26-year (!) bear market. From it 1977 peak, it had been downhill ever since. There were barely any publicly listed companies operating in the uranium industry.

You would have struggled to find anyone who even understood what the metal was used for, and how it was used.

Or as Ian Stalkers, the CEO of UraMin, is quoted in the book:

"A meeting with potential investors could literally take hours. … First, it required a full explanation of what uranium is used for (it isn't used for 'bombs'), a run-through of the fuel cycle (enrichment and so on), the safety record of nuclear reactors, long-term disposal issues and the balance of supply and demand. We were lucky if we managed to talk for 10 minutes about the company."

It was not an opportunity that the mass of investors would have jumped at when it was first presented.

However, all the clues were there. At the end of 2004/05, three crucial developments had already taken place, all pointing towards an imminent reversal of fortunes:

- The price of uranium had started to creep up. It went from USD 10/lb in early 2003 to USD 20/lb by the end of the following year (which was still far below the late-1970s high of USD 115/lb).

- Existing stockpiles of the metal, which had soared during the 1990s because of a decommissioning of Soviet nuclear missiles, had dwindled to virtually zero. The oversupply that had depressed the price for so long was gone.

- A soaring oil price, which at the time was up more than 10 times compared to its early-2000s low, provided increasing demand for cheap nuclear energy. It was only a matter of time before investment would flow towards the much cheaper source of energy.

Subsequently, the uranium price went through the roof.

The uranium price went nowhere for a quarter of a century, but then rose all the faster.

The PERCEPTION of uranium as an investment sector was extremely dire at the time.

However, the FUNDAMENTALS already looked up.

It's at this juncture that some of the greatest investments are made.

Or as I like to call it, you can exploit a perception gap to your advantage. You should invest when the broad mass of people still believes a sector to be dull, but when the facts are already pointing into quite a different direction.

2. Look out for insiders with a proven track record

The uranium market presented an unusual opportunity at the time. Stockpiles were down, production was down, and demand was nearly sure to go way up.

The broad public, the investment industry, and the mainstream media all missed the subject.

However, a few experienced players with a proven track record did spot it early on.

Stephen Dattels wasn't the only one to realise that he had to get into the uranium market. Frank Guistra, another Canadian mining entrepreneur with a stellar track record, had also formed a holding company for uranium rights.

One insider spotting an opportunity and using personal funds to invest is always interesting. Two insiders getting in on a market that no one else considers investable should get you to immediately research what the heck is going on.

Whichever market you are looking at, there are always a few investors and entrepreneurs who know more about it than anyone else. They don’t always get it right either. However, insider activity has always been one of the strongest and most reliable signals that you can use to your advantage.

3. What's hot in one country might be disregarded in another country

There is something that never ceases to amaze me in my travels and my investment research. The exact same opportunity can be viewed entirely differently depending on which country you are in and which national audience you are speaking to.

E.g., UraMin had tremendous challenges finding a suitable broker and placement agent for its plan to IPO on the AIM segment of the London Stock Exchange. There weren't any British brokerage companies that were familiar with – or even comfortable with – the uranium opportunity.

"… many UK brokers were as unaware of the uranium renaissance as institutional investors. A series of unproductive meetings took place in the latter months of 2005. All ended in failure."

British investors didn't exactly have the hots for the sector either.

In the end, UraMin signed up with a Canadian firm to act as its placement agent for the IPO and with a view to engaging North American investors. The subsequent listing on the UK market led to UraMin having mostly American and Canadian investors but hardly any British ones.

"The bulk of investor interest in UraMin Inc. centered on the North American markets. Savvy American and Canadian investors, it seemed, were far more likely to consider buying into a junior uranium mining company than their European counterparts. Stephen Dattels and Mike Beck certainly had far greater success cultivating financial arrangements in North America than Ian Stalker, and Neil Herbert had managed to achieve so far in the UK."

You'd think that in today's globalised financial markets, such regional and national differences don't exist anymore. But they do. Even 12 years after all this took place, I still find the situation to be largely the same.

UraMin went from finding almost no one to speak to in the UK, to having money thrown at it by North American investors. The company successfully raised USD 60m (then: GBP 34m), which was double what it had aimed to raise. However, the set-up involved the bulk of investors being based in one region whereas the listing was somewhere else. This situation created new problems.

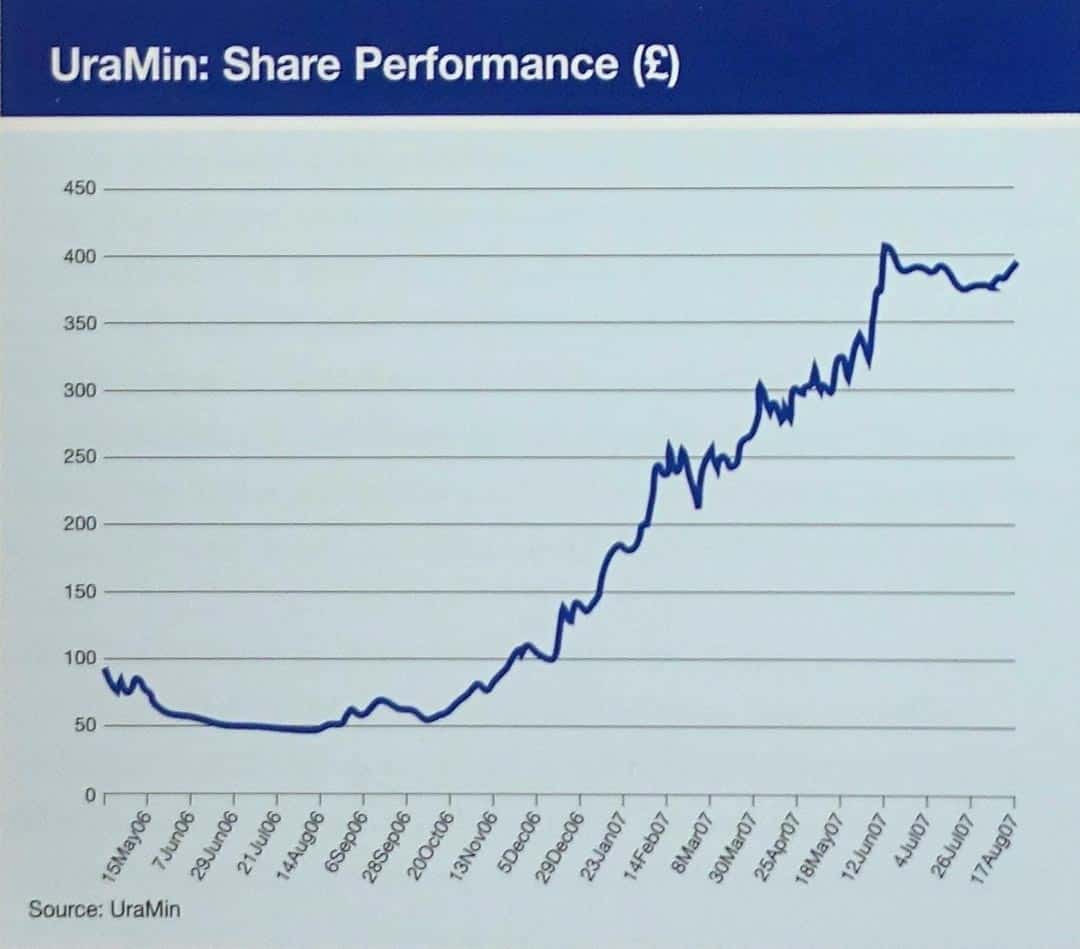

Even after the highly successful placement, there simply wasn't much interest in UraMin among investors in London. On its first day of trading, UraMin stock rose from its issue price of GBp 65 to GBp 90 because of media reporting about the spectacular placement success. But within just a few weeks, it was trading below GBp50 even. Lack of local demand played heavily into the equation.

As the saying goes, "A prophet has no honour in his own country."

UraMin initially fell through the cracks because it didn't fit neatly into the conventional categories. A negative view of this situation was that the IPO had been a failure. The positive view was that investors who paid attention were given a golden opportunity to buy more stock at insanely attractive prices. After all, the prospects that investors had eagerly poured money into at a price of GBp 65 hadn't changed when the stock was trading below GBp 50. The problem was mostly one of investors not noticing the stock (yet).

By the end of that same year, UraMin stock had finally started to get more attention. The company invested heavily in investor relations in the UK and Europe, which got more investors interested. The stock finished the year 2006 at a price of GBp 100 per share, before rising to GBp 400 by August 2007.

UraMin was short-lived on the stock market, but made plenty of money for its shareholders.

There was a lesson for other management teams and companies:

"The investor relations programme took up a large part of the company's time throughout 2006, and no one felt this more than Ian Stalker and Neil Herbert, who spent many hours drafting and redrafting press releases, meeting investors and attending conferences."

If a company doesn't have SOME angle to get investors' attention – whether through an incredibly strong investor relations department or paying insanely attractive dividends – it could struggle to get the attention it deserves. The stock market is littered with companies that are undervalued, but the stock of which will remain undervalued forever. Stocks also need to vie for investors' attention.

Unless, of course, a great management team simply leads the company on a path to being bought out by a cash-rich buyer. In that case, a company's underlying value is quickly realised by having someone pay for it in cash. That's the final lesson we are going to look at.

4. Sometimes, it pays to be realistic and put a company up for sale

As one famous German investor likes to say on his TV show, "There are no great companies, there are only great entrepreneurs."

Which, of course, references the quality of the management team in general. Every investment opportunity hinges on the quality of the management team.

One little-discussed aspect of this is the question of whether the management team has a realistic appreciation of the company's position within its industry.

Put more bluntly, there are occasions when a management team has to concede that everyone is better off if it puts the company up for sale – which is difficult because it usually leads to the entire management team and board losing their jobs!

Also, who wants to leave a party when things are the most fun? Making the decision to call it quits and focus on maximising a buyout price for a company is an extraordinarily hard decision to take. However, it is quite regularly the one decision that a board really should have the guts and the sense of realism to take.

I wasn't surprised to read that Dattels and his colleagues had that rare quality of knowing when to quit:

"The trend towards a smaller group of larger uranium companies had significant repercussions for UraMin, something that its management realised early on. "The sector was not a large one – it had already seen several significant mergers and more were rumoured," notes Neil Herbert. "Despite the rapid progress we had made, we were in danger of becoming a relatively small operator.

…

On 19 February 2007, Reuters reported that UraMin was planning a strategic review of its assets in light of the recent consolidation of the sector.

In effect, analysts believed, the company had just put itself up for sale."

Companies can put themselves up for sale by hiring an investment bank and making a public announcement, or they can de facto put themselves up for sale by feeding information into their industry's rumour mill.

Steve Dattels decided that "we should take the initiative and evaluate the merger possibilities rather than wait for the telephone call."

UraMin hired advisors and went through an official process of allowing prospective acquirers access to its internal information.

Following the process of inviting bids, the company came to an agreement with French nuclear power company, AREVA. In June 2007, UraMin's management team agreed to a takeover offer that valued the company at USD 2.5bn. The entire purchase price was payable in cash.

Investors who had bought in at the bottom of GBp 50 per share made 8 times their money within just 12 months.

One of the earliest institutional backers of the venture reportedly made 22 times their money in just 24 months.

The very earliest investors and the management team, no doubt, reaped even bigger rewards. Good for him – this was a well-deserved pay-off for a group of entrepreneurs who opened up an opportunity to other investors. Anyone who made the effort to analyse it could have easily bought shares on London's AIM market.

To this day, I regularly check on what Dattels is up to today. He is the kind of insider that I like to follow.

Is there anything new under the sun?

I had a blast finally reading this book, not the least as I had owned UraMin shares for a brief time back in the days (though I sold out at a relatively small profit).

There would have been other points worth mentioning, but I wanted to focus this Weekly Dispatch on the most significant aspects.

Also, it's worth pointing out that many of these ground rules never change:

- Utilising a perception gap as described in point no. 1? That's what I did towards the end of last year in the case of Gazprom.

- Looking out for significant insider action and a company not getting sufficient recognition among its local investor community? The Israeli gas company that I featured in my April 2019 report fits that profile to a "t" (and its stock is also currently in the doldrums).

- A company being well-advised to put itself up for sale because it is (valuable) prey rather than a predator? My most recent report on a British takeover target is an example cut from the same cloth, though without the board-approved "Strategic Review" having led to an official sales process (yet).

In that sense, you could say that the stock market shows the same patterns over and over again. I would only add that it also takes time and effort to research the finer details.

Few things give your investment research a better grounding than a thorough understanding of history and its ever-repeating patterns. That's why I love digging out books such as the one about UraMin.

Come to think of it, reading it even inspired me to dig deeper into another opportunity that recently crossed my paths. To be featured in one of my research reports by the end of this year (Members get the full story and first dibs as always)…

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post:

Get ahead of the crowd with my investment ideas!

Become a Member (just $49 a year!) and unlock:

- 10 extensive research reports per year

- Archive with all past research reports

- Updates on previous research reports

- 2 special publications per year