Buying farmland in one of the well-established bread baskets of the world at 1/900th (or 0.0011%) the price of US farmland?

To David Iben, owner of value investment firm Kopernik Global Investors, this seemingly extreme valuation disparity makes sense:

"On the Ukrainian side we own a company called Astarta, which is in agriculture. It is one of the top 5 agriculture companies in Ukraine. They have 25% of the market share of Ukraine's sugar. … In the US you can buy high quality Iowa farmland for close to USD 14,000 an acre. In Ukraine, we can buy this for USD 15. That means the US is 923 times more expensive than Ukraine."

With everything that has been going on recently, is now the time to pile into Ukrainian agriculture stocks? Could stocks such as Astarta land you the ultimate value investing bargain? Notably, all of these six stocks trade on exchanges that most Western investors can access – London, Warsaw, Paris and Frankfurt.

With almost no prior knowledge about Ukrainian farmland plays, I set out to educate myself from the ground up (no pun intended).

What makes Ukrainian agriculture so successful?

It's long been well-known that Ukraine is one of the world's bread baskets. Its 40m people represent just 0.5% of the world's population, but the country can meet the food needs of 600m people or about 9% of the world's calorific input.

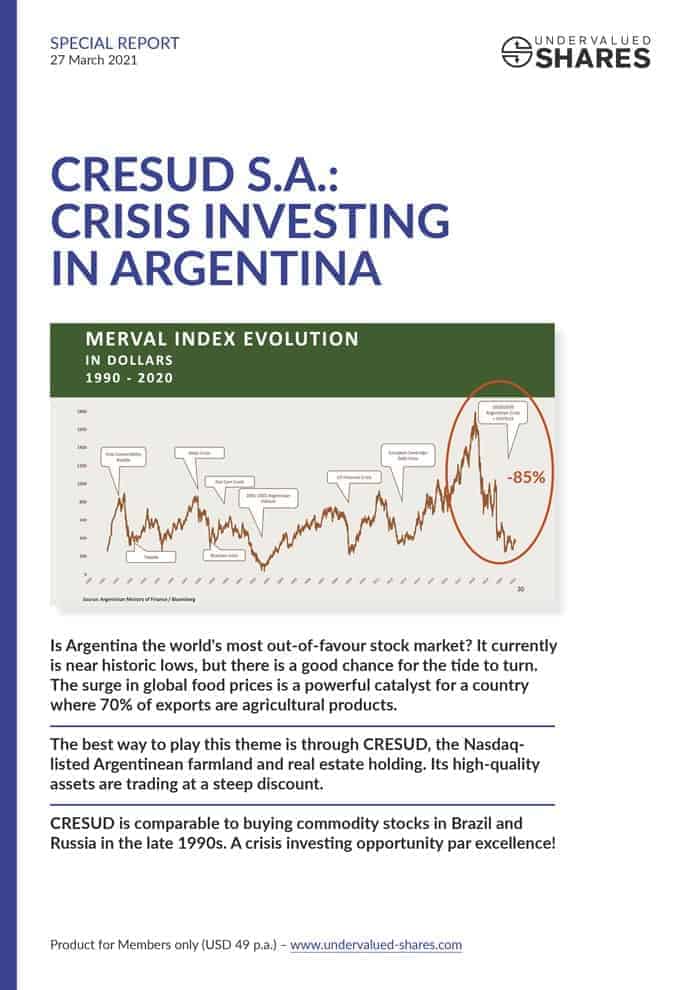

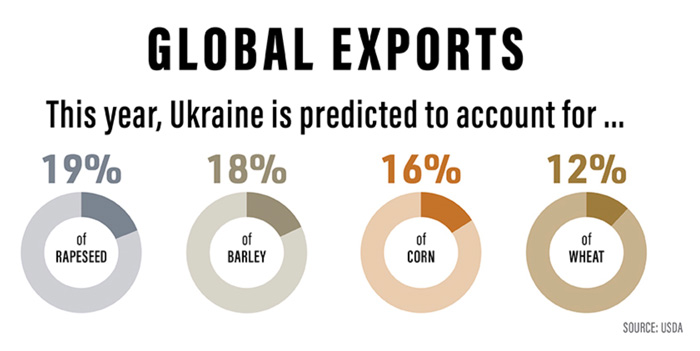

Ukraine is staggeringly important to global agriculture, as you can see from the following recent figures provided by the US Department of Agriculture:

- 1st in the world in exports of sunflowers and sunflower oil.

- 6th in the world in barley production.

- 6th in the world in corn production.

- 7th in the world in rapeseed production.

- 9th in the world in wheat production.

- 9th in the world in soy production.

Ukraine's contribution to the world's food production becomes clearer when you look at the country's percentage share in global exports of key produce.

Source: US Department of Agriculture.

Indeed, the yellow stripe in Ukraine's flag represents the endless wheat fields that characterise the country. The blue stripe represents wide blue skies that come with it.

The country has long been one of the poorhouses of Europe, but its agriculture industry has always been highly competitive:

- Ukraine quite simply has the most arable land area of all European countries. Totalling 41.5m hectares (or 102.5m acres), its agricultural land encompasses the entire (not just agricultural) land mass of Italy and Portugal combined.

- Much of its soil is hyper-productive. A quarter of the world's "black soil" is located in Ukraine.

- The giant size of fields makes for economies of scale, similar to the advantages enjoyed by the US in its mid-West agricultural belt.

- Ukraine is not just large, but also entirely flat.

- As one of the poorest European countries, Ukraine has never experienced a shortage of cheap labour.

- The country has a decent infrastructure, including access to Black Sea ports.

- The national currency, the hryvnia, had long been weak which made exports more competitive. Costs are paid locally in weak hryvnia, export income is earned in hard dollars.

Given its natural advantages, it's surprising that Ukraine has been as poor as it's been. We'll get back to that later.

Which companies are the main contenders?

There are six Ukrainian agriculture companies that Western investors can buy into:

- Kernel Holding (ISIN LU0327357389), listed in Warsaw and with several German OTC listings.

- Astarta Holding (ISIN NL0000686509), listed in Warsaw.

- IMC (ISIN LU0607203980), listed in Warsaw.

- AgroGeneration (ISIN FR0010641449), listed on Euronext Growth (Paris/Amsterdam) and with several German OTC listings.

- MHP (ISIN US55302T2042), listed in London as GDR and with several German OTC listings.

- Ovostar Union (ISIN NL0009805613), listed in Warsaw.

Despite the current circumstances, all of these stocks continue to trade as normal. After all, Ukrainian stocks are not the target of Western sanctions.

As you will realise throughout this article, the diversity among these companies represents one of the biggest opportunities but also one of the main difficulties of this investment theme:

- Kernel Holding utilises 506,000 hectares (1.24m acres) to grow corn, sunflowers, and wheat. It's not just Ukraine's largest agricultural producer, but also the largest trader of agricultural products. It owns its own fleet of boxcars for transport by railway, countless storage silos, and even two harbour terminals on the shores of the Black Sea.

- Astarta Holding farms 220,000 hectares (544,000 acres) to grow wheat, corn, rapeseed, soy, and sugar beets. Much of its wheat was historically destined for export, whereas its sugar beets were mainly sold in the domestic market. The company also operates sugar mills. With a 20-30% market share, it's the #1 player in the Ukrainian sugar market.

- IMC (als known as IMC Farms or IMC Agro) is one of the smaller producers with 123,000 hectares (304,000 acres), which it uses for growing wheat, corn, and sunflowers.

- AgroGeneration has 60,000 hectares (148,000 acres) of land in active use and splits its production between grains (60%) and oils (40%).

- MHP is an outlier as it produces primarily poultry, although it also grows some corn, wheat, and rapeseed. The company controls 380,000 hectares (939,000 acres) of land.

- Ovostar Union produces eggs and egg products. At last count, it produced about 1.6bn eggs a year, a third of which were turned into egg products.

One of the reasons why I decided to look at these stocks is the fact that they generally had low valuations even before the war broke out. I checked back to a 21 June 2021 in-depth research report that leading Ukrainian broker Dragon Capital published about the country's agriculture stocks. Astarta Holding and IMC were both projected to pay a 12% dividend yield, and MHP as well as Kernel Holding were trading at just 3 times EBITDA. With the exception of Ovostar Union, all of these stocks were valued at forward price/earnings ratios of just 4-5, or about half the typical valuation of their emerging market peers, and just a third the valuation of their developed market peers.

Ukrainian stocks experienced a sell-off when the conflict broke out, and MHP reported the destruction of a large storage facility with USD 8.5m of poultry products due to shelling. However, farmland is an asset that usually gets to see the other side of military conflict. Unless large-scale nuclear or chemical warfare renders the entire country uninhabitable, Ukrainian farmland will remain usable.

Should contrarian investors take a closer look at these stocks now, and if so, what are some of the important factors to bear in mind?

Obvious and non-obvious factors

There is currently no detailed information available about the precise level of physical damage to the operations of these six agricultural companies. This is not to say that no damage may exist; the companies may simply no longer be able to keep the public up to date.

An important factor to consider is whether any of the plant-growing companies will be able to make use of the upcoming planting season. Short of a sudden end to the war or a ceasefire agreement of some kind, it seems likely that these companies will miss out on a very significant percentage of this year's crops. As ING Bank reported on 4 April 2022:

"Ukraine's agriculture ministry estimates that total spring acreage in the country could drop by around 21% YoY to 13.4m hectares this year, due to the ongoing military conflict with Russia. The ministry also reported that around 600k hectares of land has been sowed (around 5% of projected acreage) to date, with 21 out of 24 regions starting the sowing process."

The other major factor to bear in mind is how the political landscape will look like once the conflict is over (which it will, one day). This is where everyone will have their own view. Some of you will believe that Putin wants to occupy and permanently rule the entirety of Ukraine – in which case, some of these agricultural companies which have published political statements supporting Ukraine's war efforts (check here, here, and here) will be disadvantaged. Others will believe that Putin is focussed on occupying parts of Eastern Ukraine but only pursues temporary military operations in the Central and Western part of the country – in which case, these companies might go back to some kind of normal.

I place myself in the camp of those ≈4bn people whose home countries are sticking to a degree of impartiality. Brazil, Mexico, India, Pakistan, China, Indonesia, Bangladesh and much of Africa supported a UN declaration condemning the war but remain on the sidelines in other aspects and continue to trade with Russia. In line with that keeping a degree of neutrality, I have a genuinely open mind as to the eventual outcome of this conflict, i.e. I don't have a particularly strong gut feeling one or the other way. I do hear all the points about Russia's military having tremendous problems, but I also wonder whether, without external intervention, the sheer mass of Russia isn't likely to eventually overwhelm Ukraine and force a surrender (the situation strikes me like Texas trying to fight the federal US).

What I did take notice of, though, was the rather strong performance of the agricultural stocks during the past three weeks. This appeared counter-intuitive and made me curious.

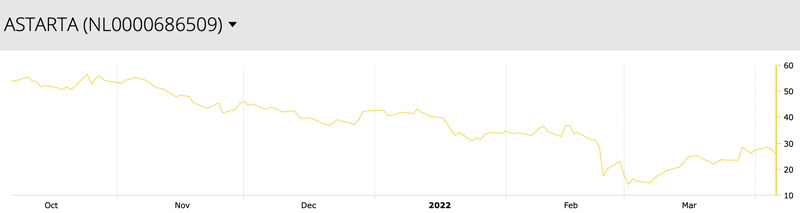

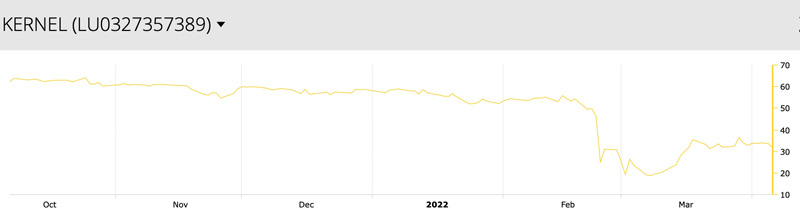

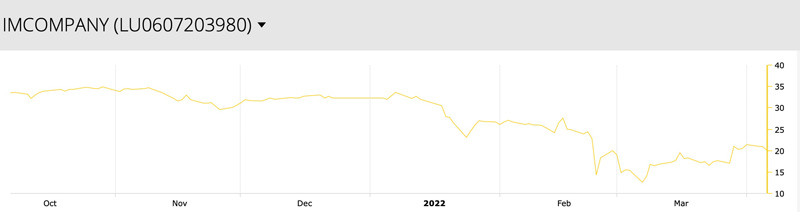

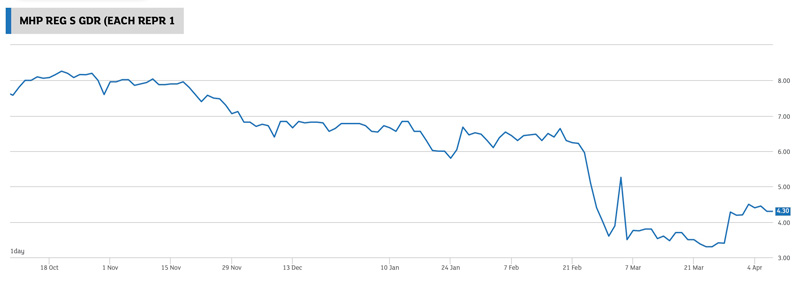

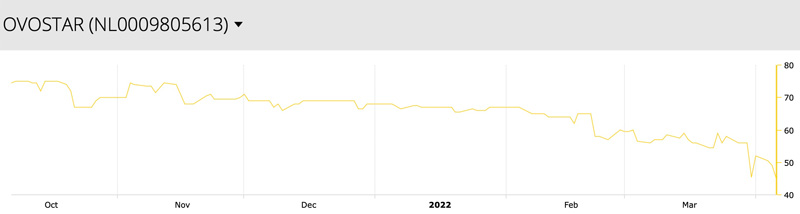

As the following charts show, all of these agricultural stocks dropped dramatically during the early part of the conflict, no doubt also in light of the fact that Ukraine's economy is currently en route to shrinking up to 40% this year. However, four of the six have since recovered a surprisingly large (!) part of the losses. The stock prices of Kernel Holding, Astarta Holding, IMC and MHP are up 30-60% since their March 2022 lows.

Astarta Holding.

Kernel Holding.

IMC.

AgroGeneration.

MHP.

Ovostar Union.

What could have caused the massive swing, and where does this leave investors who are currently considering an investment? Is it just a dead cat bounce or a sign off a more meaningful turn?

"Wealth, War & Wisdom"

I do like consulting the know-how of people who have been through similar situations before or have looked through mountains of historical evidence to educate themselves. One of the definitive books about investing during times of war is Barton Biggs' "Wealth, War & Wisdom", published in 2008. I've read it again in its entirety, to gather what wisdom we may glean from it and to help us make sense of the current situation.

The late Barton Biggs had worked at Morgan Stanley for over 30 years, and he was one of the world's foremost investment strategists. My copy of his book has a foreword by the late David Swenson, Chief Investment Officer at the Yale University endowment fund – himself a legend, too.

The #1 conclusion of the book is summarised in Swenson's foreword:

"The stunning conclusion that Biggs reaches is that in many cases the market foresees dramatic shifts in the prospects for the warring parties that completely escape contemporary observers. Barton Biggs challenges us to consider the possibility that the wisdom of crowds, as reflected in the level of stock prices, surpasses the wisdom of even the most astute observers of the current scene."

As Biggs put it in the main part of the book:

"Looking back with the perfect vision and the perspective of today, we can identify the victories that were the great turning points. However, at the time, in the fog of war, it was far from clear that the tide had turned. Did equity markets with the unique wisdom of the crowd sense these moments? I think the evidence is that they did, while the press and the so-called expert commentators and strategists mostly did not."

He cites examples from the Second World War as evidence:

"The London stock market deduced in the early summer of 1940, even before the Battle of Britain at a time when the world and even many English despaired, that Britain would not be conquered. Stocks made a bottom in early July although it wasn't evidence until October that there would be no German invasion in 1940 and until Pearl Harbour 18 months later that Britain would prevail.

Similarly, the German stock market, even though imprisoned in the grip of a police state, somehow understood in October of 1941 that the crest of German conquest had been reached. It was an incredible insight. At the time, the German army appeared invincible. It had never lost a battle; it had never been forced to withdraw. There was no sign as yet that the triumphant offensive into the Soviet Union was failing. In fact, in early December a German patrol actually had a fleeting glimpse of the spires of Moscow, and at the time Germany had domain over more of Europe than the Holy Roman Empire. No one else understood this was the tipping point.

The New York stock market recognised that the victories at the battles of the Coral Sea and Midway in May and June of 1942 were the turn of the tide in the Pacific, and from the lows of that spring never looked back, but I can find no such thoughts in the newspapers or from the military experts of the time."

It all seems so obvious with the benefit of hindsight, so why did no one (except the stock market) come to the right conclusions at the time?

Biggs concluded that so-called expert commentators often get distracted by the wrong factors:

"A barrage of defeats and surrenders had engendered intense criticism of the management of the war and the commanders in the field. The wise men of the media were so busy wringing their hands that they didn't grasp the significance of the battles of the Coral Sea and Midway as the high-water mark of Japan's grand design for empire and of its attack on the United States."

Biggs was particularly critical of the role of media commentators, and how they are often influenced by the narratives that their governments would like them to put out there. Here is what Biggs concluded about the self-appointed paper of record:

"In fact, the American media had been wrong on the war from the beginning. Fed by the US War Department, the New York Times in the first weeks after Pearl Harbour exaggerated any small success of the allies and under-reporting the damage to the Pacific fleet. For example, five days after Pearl Harbour, on December 12, 1941, the banner headlines were JAPANESE CHECKED IN ALL LAND FIGHTING; 3 OF THEIR SHIPS SUNK, 2ND BATTLESHIP HIT. The story reported that one of the three ships sunk was also a battleship. It was pure fiction. Only one relatively insignificant Japanese destroyer had been sunk."

Pure fiction, fed by Washington, and portrayed as facts in the New York Times – the surprise!

Do similar circumstances apply today, and is the recovery of Ukrainian agriculture stocks an indicator that a similar pattern is playing out in this conflict?

I am not going to make a call either way. When this conflict started, I made a conscious decision that I would spend relatively little time on following its details. Why? Because experience shows that during a war, no source of information is reliable. The fog of war always produces the foggiest of war propaganda – never mind the deep complexity of the current subject matter. Also, I've lived through the era of Tony Blair joining a war over fictitious weapons of mass destruction. At the time, we were sold fabrications that linked Saddam Hussein with 9/11, al-Qaeda, and weapons of mass destruction. Having just put up with two years of getting blitzed with propaganda about the pandemic, I decided that instead of spending my time doom-scrolling through clickbait-y mainstream media reports and listening to either side spinning their version of events, I focus on a more productive use of my time.

However, even with my cursory glancing at the situation for a few minutes every day, I cannot help but wonder if we might not yet see a few surprising outcomes – and of the kind that are more accurately predicted by markets rather than politicians, so-called experts, and the usual media commentariat.

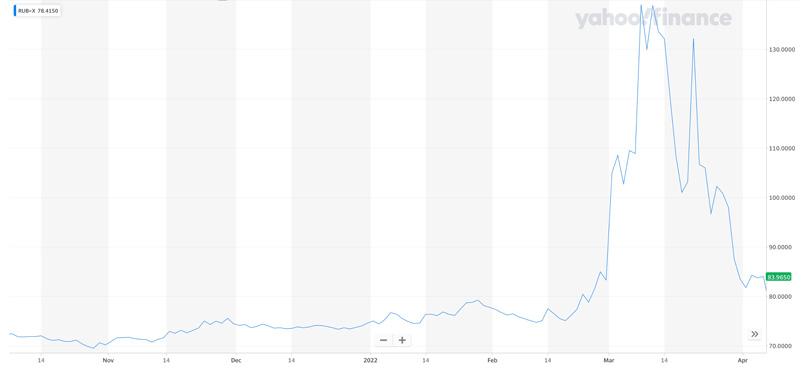

E.g., a mere week after President Biden tweeted "As a result of our unprecedented sanctions, the ruble was almost immediately reduced to rubble.", the ruble was almost back to the level it traded on before the invasion. "Rubble no more", the ruble said.

RUB vs. USD.

While Western politics and the media try to explain away the ruble's current recovery, I do wonder if the real story could eventually be similar to what Biggs described in his analysis of the Second World War. Surprise outcomes wouldn't surprise me at all, and my sceptical stance towards corporate media outfits is well-known.

With all this in mind, could it be wise to ignore some or all of the current narratives? Could Ukrainian agriculture stocks unveil yet more surprise upside?

A drive-by valuation of land reserves

David Iben's analysis is true. Relative to their market caps and enterprise values, Ukrainian agriculture stocks have an extraordinarily low valuation per hectare/acre of land.

Up-to-date, precise figures are currently hard to come by, but the valuations roughly boil down to the following (based on enterprise value, i.e. including debt):

| Company | USD per hectare | USD per acre |

| Astarta Holding | 1,000 | 400 |

| Kernel Holding | 2,500 | 1,000 |

| IMC | 2,100 | 840 |

| AgroGeneration | 850 | 340 |

These figures don't quite match up with the USD 15 per acre valuation stated by David Iben. He's probably right, though, if you make assumptions about the value of the companies' other assets. Besides land, all of these companies own facilities, equipment, intellectual property, and other assets – which I left out for the purpose of the table above, valuing these companies as if they had nothing but the land. If you take the other assets into the equation, the remaining value spread across the land leases will, indeed, be a lot lower. How low? That depends on what value you assign to these assets. Book value does not seem to be the right value to apply, given the Ukraine's current situation. Facilities could be destroyed, or access to them lost if the map of the country got redrawn. It's really anyone's guess what these assets are worth.

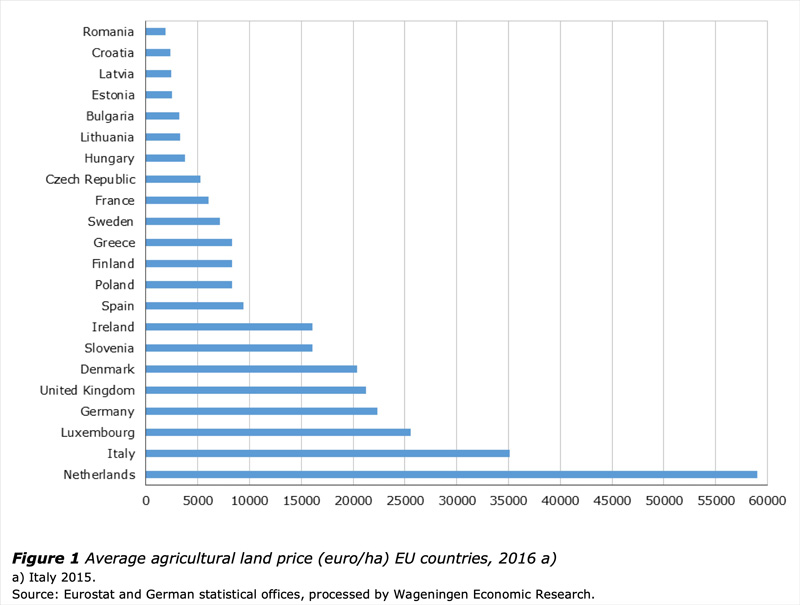

However, even in the absence of a precise figure, it's clear that these Ukrainian agricultural stocks represent tremendous value. Assume, for argument's sake, that all assets other than the land would be worth zero. You'd buy this land at about 10% the valuation of Polish farmland. This is not a precise way of valuing, but it provides you with an order of magnitude understanding. From this perspective, you could say that these four agricultural companies may well represent the ultimate cheap land play and a bet on an eventual recovery of Ukraine's agriculture sector – especially if the market took another dip and you bought then.

Outside of my back-of-the-envelope calculation, the question has a lot of nuance and complexity, and the assessment also depends on your interpretation of the current course of events, your expectation of the desired outcomes of the different key stakeholders, and the likelihood of these different key outcomes.

E.g., the majority of the land held by Astarta Holding and IMC is in Central and Western Ukraine. If Ukraine was indeed the superior military force that much of the Western media has made it out to be, these agriculture companies could return to relatively normal operations once Ukraine has won back full control over this part of the country. The same would hold true if Russia did not aim to permanently conquer this area and merely wanted to replace the current government. Just as much, one can argue that these companies would stand to lose the most under an authoritarian, Russian-backed Ukrainian regime. Astarta Holding and IMC were both very vocal in supporting the Ukrainian government ("Together to Victory! Glory to Ukraine!"), and as a result could become a political target of a new Russian-backed government.

On the other hand, AgroGeneration's land is in the region of Kharkiv, which is right on the border of the Russian-controlled regions and thus could fall permanently under some kind of Russian influence. Maybe it is for this reason that, contrary to Astarta Holding, AgroGeneration only made rather measured statements about the situation. Is this an advantage or a disadvantage for the company and its shareholders? You be the judge. In any case, the potential ramifications of the conflict could differ for this company.

There are manifold soft factors which could come into play as the situation moves forward. E.g., the majority of MHP's board members are from Western countries – which Russia now deems "unfriendly" nations.

And yet, all of these political questions could pale in comparison to the challenges and opportunities thrown up by another peculiarity of Ukraine that is currently much less talked about.

Land ownership in Ukraine is not entirely straightforward. Surprisingly, this could yield both positive and negative changes for the companies mentioned above. It could even become a driver of the stock prices in a way that no one currently seems to have on their radar.

Leaseholds, freeholds, and pending reforms

Before the conflict in Ukraine broke out, the country was known as an example of how NOT to do economic policies.

In all those years since the end of the Soviet Union, Ukraine had never managed to get back to its pre-1990s level of GDP per capita – unlike Russia. Russia already reached its pre-1990s level of GDP in 2006, and it has moved on a lot further from there.

Ukraine never quite managed to find the right formulae for advancing economically, and this extended to its agricultural sector – again, unlike Russia. In Putin's Russia, agricultural exports have grown by a factor of 16 between 2000 and 2018. The country had been a net importer of wheats during the 1990s, and subsequently became the world's top exporter, providing 20-25% of the global wheat exports.

Even The Economist, by no means a fan of Putin's policies, recognised in its 1 December 2018 issue: "Russia has emerged as an agricultural powerhouse: Enterprising farmers have overcome the legacy of Soviet collectivisation. … Since the Soviet Union's collapse, farming has undergone a gradual transformation from 'a fantastically ineffective collective model to effective capitalism', says Andrei Sizov, head of SovEcon, an agricultural consultancy in Moscow."

Despite its legendary black soils, Ukraine's agricultural productivity remained lower than many other European countries with less fertile soils. On 31 October 2019, Vox Ukraine reported: "Ukraine's agricultural productivity is a fraction of that in European countries with 2014 agricultural value added per hectare of $ 413 compared to $1,142 in Poland, $1,507 in Germany, and $2,444 in France."

Why the difference?

As the Washington, DC based Brookings Institution explained in a 3 March 2016 analysis: "The answer lies in the administration of the country's farmland. Today, more than 25 percent of the farmland is still in state hands. … Although land of previous collective farms has been privatized 15 years ago, a moratorium on farmland sales and the large portion of the country's state land significantly constrain growth potential."

Apparently, 27% of the agricultural land in Ukraine has not even been mapped.

Indeed, together with Belarus, Ukraine remained one of the last two European countries where farmland sales were prohibited. Globally, this put Ukraine into a tiny club of just seven nations that includes North Korea and Venezuela as notable members.

The companies discussed in this article don't as such own most the land, they merely benefit from long-term leaseholds signed on advantageous terms. The valuation of land granted under leaseholds (= rentals) is different from valuing freeholds (= outright ownership), which needs to be taken into the equation. It could well be quite similar, because long-term leaseholders often end up being able to buy the freehold for a relatively low amount. However, the proof is in the pudding. Also, it was reported in the past that these leaseholds came with a contractual right to purchase the land once the law changed, and to purchase it for a rather advantageous price.

There are other reasons why 1:1 comparisons of Ukrainian farmland to other farmland will never be accurate. E.g., as David Iben also pointed out, Ukrainian farmland is not as productive (yet) as Iowa farmland, which is why the valuation comparison quoted at the outset of this article is more illustrative rather than an accurate analysis. However, what seemingly puts a further damper onto Ukrainian agriculture could also become one of the greatest – and non-obvious – opportunities.

On 1 July 2021, the 2001 moratorium that prohibited the sale of farmland came to an end. Under new legislation, Ukrainians can now buy and sell farmland, at least up to 100 hectares. The plan before the outbreak of hostilities was that from 2024 onwards, Ukrainian legal entities were going to be able to buy up to 10,000 hectares.

Whether foreign entities should be allowed to buy land remained one of the bones of contention. The International Monetary Fund, a major creditor of Ukraine, had pressed for an end to the moratorium, and various other international organisations backed the idea of granting foreign capital access to the Ukrainian agricultural sector. However, between 60-80% of the Ukrainian population oppose the idea of large-scale land privatisation and it remains to be seen whether globalist organisations will succeed in forcing their will onto the Ukrainian people. Their fear of corruption and a loss of control over the country's destiny is not an unreasonable one. In November 2020, then Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal announced that 5m hectares of agricultural land had "disappeared" from state ownership. That's over 8% of the country's land mass stolen – no doubt, by people of influence. Ukraine has its own set of oligarchs, although I anecdotally noticed that post-2014, the Western commentariat often relabelled them "entrepreneurs". Whatever the wording of the day for special interest groups are, this country has been a cesspit.

Will Ukraine's people manage to keep foreign investors out, and how will the answer to this question potentially influence the long-term fate of the companies featured in this article? It's complex, and there may not be a straightforward answer even when you leave the current political issues aside.

In situations such as these, the question of what constitutes a foreign investor is usually not straightforward. E.g., Russia has long had similar regulations banning foreign investors from farmland purchases, but the legislation left a widely-known loophole whereby foreign investors create a Russian subsidiary which then sets up another Russian subsidiary that buys the land – problem solved! Even though foreign ownership is technically speaking prohibited, foreigners are known to control about 5% of the Russian farmland. Never mind the fact that companies can nowadays be of an unclear nationality. E.g., Kernel Holding gets ranked by mainstream media as the third largest private sector company of Ukraine, but it's actually owned by a Luxembourg holding company, which in turn is controlled by a Ukrainian billionaire oligarch entrepreneur.

Kernel Holding, as the largest of the companies, controls 1.2% of Ukraine's agricultural land. There are a few other large farmland owners that are not listed on a stock market, including UkrLandFarming (570,000 hectares, probably owned by Russian investors), NCH Capital (430,000 hectares, US private equity), and Continental Farmers Group (195,000 hectares, part of Saudi Arabia's Sovereign Wealth Fund's efforts to secure food supplies). In total, the large agricultural corporations operating in Ukraine are estimated to control no more than 15% of the total farmland. Usually, in industries that benefit from economies of scale, you would expect the single largest player to control anywhere from 10-30% of the entire market, and the top two or three players to make up over 50%. In other words, not only is there a lot of land privatisation waiting to be done in Ukraine at some point, but there is also a need for consolidation among existing players. The likes of Kernel Holding should really be about ten times as large to achieve true economies of scale.

One day, some of the existing players may get there. Much as companies do get caught up in politics, they often come out of military conflicts as entities that are needed by the victors to rebuild. Deutsche Bank was famously intertwined with the Nazis, and just as much famously successful played a key role in rebuilding post-war Germany which turned it into one of the wealthiest financial institutions in the world. It's usually directors that get punished for being on the wrong side of history, but the companies live on. The smartest directors, entrepreneurs and technicians often make their skills useful to the new regime in exchange for being let off the hook (history's most famous example possibly being that of Wernher von Braun).

The big question is, who is going to win the conflict in Ukraine – if there will even be such a thing as a "winner"? There are manifold scenarios for the leading agricultural companies once the conflict is somehow settled and the shooting stops.

E.g., Western Europe has a long history of providing economic backing to these companies, even in cases where this made billionaire oligarchs entrepreneurs richer. As the Oakland Institute reported on 6 August 2021:

"The largest Ukrainian agribusinesses have each received far more from international lending institutions like the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the European Investment Bank (EIB). … In recent years, recipients of these loans have included Kernel, MHP, and Astarta, all among the top five largest agribusinesses in Ukraine in terms of overall land holdings. For instance, Kernel has received US$248 million in several loans from the EBRD since 2018, MHP has received about US$235 million from the EBRD since 2010 and about US$100 million from the EIB in 2014, and Astarta has received US$95 million from the EBRD since 2008 and about US$60 million from the EIB in 2014. Foreign financial institutions like the EBRD and EIB are not just financing Ukraine's most powerful agribusinesses and landholders, but companies owned by some of the richest individuals in the country - MHP founder Yuri Kosyuk was ranked the 11th richest person in Ukraine in 2019, while Kernel founder Andriy Verevskiy was ranked 19th."

Ukraine may move closer to the West, and agriculture is a key industry that provides 14% of Ukraine's jobs and contributes 10% to its GDP. The West is already familiar with the largest companies that operate in the space, and these companies have the right size to provide Western aid institutions with the necessary level of impact in the country. These companies could find themselves receiving large-scale financial support from Western institutions eager to help them back on their feet.

This could include helping these companies grow to an altogether different size. The aim of consolidating ownership of farmland in fewer hands was already set out in the May 2021 white paper "Strategy for the development of land relations in Ukraine", which was co-funded by the European Union. As the document stated, the necessary land reforms will:

- "kick start a gradual consolidation of land ownership"

- "promote consolidated land use"

- "facilitate land consolidation"

Could Brussels' goal be any clearer? Keep in mind, the EU capital is home to over 30,000 corporate lobbyists and not a friend of small-scale entrepreneurs. This could benefit the largest players in Ukrainian agriculture. As the Oakland Institute put it, there is "support for agribusinesses, not small farmers".

Just as much, Russia having a stronger say over Ukraine could also yet be to a long-term advantage of these companies (unpopular as this opinion may be). Putin has proven that he knows how to turn around a country's ailing agricultural industry, and he may wield his influence to apply the same in Ukraine.

Depending on your existing viewpoints and political leanings, you can interpret both scenarios in opposite ways. E.g., the EU has a long history of bleeding Eastern European countries dry by attracting much of their young and educated to the West, which has turned entire regions of Poland, Hungary and the Baltics into geriatric wards and made them addicted to EU subsidies and dependent on remittances. Russia, in turn, could be in no positive inclination towards some of the Ukrainians (and foreigners) who are involved with these agricultural companies and wreak havoc to their land lease agreements.

Who knows?

In amidst the deep complexity of this conflict and the political activities that are going on behind the scenes, I don't currently see a clear path forward for Ukraine or the companies that operate there.

However, is is evident that Ukraine's agricultural sector is key to the country's future, and it could make for a potential quick win for whoever ends up in a position of power. If (or when) post-war Ukraine found itself in need of money, privatising land by selling off large tracts of agricultural land to large corporations could be a quick way to raise funds and potentially deliver the bargain of the century to those companies that can participate in the process. Preference would probably be given to Ukrainian oligarchs entrepreneurs, and the conversion of leasehold land to freehold land would probably be done on advantageous financial terms (so that the valuation difference between leasehold and freehold turns out smaller in the end than many would expect). In any case, the underutilisation of the Ukrainian farmland, the outdated fragmentation of the industry, and the subsequent undervaluation of these companies' growth potential really do stick out. Or as the Atlantic Council concluded on 22 June 2021: "Land reform can make Ukraine an agricultural superpower".

Which leaves only one conclusion.

Source: An excellent primer on the subject (source: Oakland Institute, 6 August 2021).

Watch this space!

I have been in the investing arena for long enough to know that such situations are worth following closely, even if they sometimes take years to materialise.

Just before the war, land sales in Ukraine took place at an average of USD 1,420 per hectare (USD 570 per acre). In other countries of the region, prices gravitated towards USD 4,000 per hectare (USD 1,600 per acre) once reforms had been implemented. In Germany, prices are on average USD 25,000 per hectare but can range up to EUR 80,000 per hectare in the country's south. The valuation differences are huge, and Ukraine is unlikely to catch up with Western valuations during our lifetime – but it's clear that there is potential for prices rising by a multiple given the quality of the Ukrainian soil and the relative ease with which technology can nowadays be used to improve productivity. Even relative to the prices paid in Ukraine before the recent outbreak of hostilities, the stocks featured in this article currently represent a cheap way to get exposure to this asset class.

Reforming and modernising the Ukrainian agriculture sector could create billions of new wealth. Large-scale opportunities such as the one presented by Ukrainian agriculture don't come around all that often. If you weren't around to buy apartments in downtown Prague in the early 1990s or seaside land in Croatia during the initial post-war years in the early 2000s (when everyone told you not to!), this may yet become your generation's next big chance.

(Or it may all come to nothing – just to have mentioned that possibility, too.)

Which of these stocks should you buy right now, or should you buy any of them at all? At this stage, I haven't made up my mind yet. What I do know for sure, though, is that following corporate media is not going to lead you to the right conclusions. Barton Biggs demonstrated as much. Seeing the blatantly tendentious reporting in Western European and American media, in particular, I'd say that nothing much has changed in this regard since the 1940s. Who knows, maybe the markets are already signalling us that the end of the conflict is nearer than we are currently made to believe?

Which makes it all the more interesting to watch for signals provided by the wisdom of the crowd – aka, the stock market – and draw your conclusions from there.

If you are an institutional investor, you can further your insights into this market by speaking to the Ukrainian stock market broker Dragon Capital in Kiev, or their US collaborator in New York, Auerbach Grayson. Dragon Capital maintains a helpful free online directory of major Ukrainian companies that includes some key figures and recent news. Auerbach Grayson, in turn, helps international investors with market access both in terms of trading and research.

I know that many of you will currently be doing (or attempt to do) something similar to what the Financial Times summarised in its 24 March 2022 article: "Hedge funds search for bargains in Russian and Ukrainian bonds". Tragic as some political and humanitarian situations are, capital markets always continue to work out where to steer capital for its most productive use. The current situation in Ukraine and Russia is no different in this regard, and I'll continue to scope out potential new ideas for both the readers of my free Weekly Dispatches and paying Members. "How to invest in Russia or Ukraine at this time" is the single-most asked question in emails to me since I set up Undervalued-Shares.com; other colleagues in the industry report a similar level of interest.

The world is a big place, though, and while I continue my research into distressed Ukrainian and Russian assets, you might want to look at comparable, easily available alternatives, too.

If you like the idea of crisis investing and agriculture all wrapped into one, you might be interested to hear about a report that I published just under a year ago. It has already yielded a 65% gain for my Members, and it should have even further to run.

Crisis investing in Argentinean agriculture

Luckily, there's no shooting or tanks involved with this stock. Agriculture in Argentina is a safe haven!

After a multi-year crisis, the country is now on the cusp of recovering. Prices for agricultural prices are surging, and CRESUD – the Argentinean farmland and real estate holding – is set to benefit massively.

Its stock is listed on Nasdaq and with a compelling valuation, its run should have just begun.

Crisis investing in Argentinean agriculture

Luckily, there's no shooting or tanks involved with this stock. Agriculture in Argentina is a safe haven!

After a multi-year crisis, the country is now on the cusp of recovering. Prices for agricultural prices are surging, and CRESUD – the Argentinean farmland and real estate holding – is set to benefit massively.

Its stock is listed on Nasdaq and with a compelling valuation, its run should have just begun.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post: