Image by arapix / Shutterstock.com

Few investors would associate Egypt with fast-growing tech companies that are creating billions of dollars in new shareholder wealth – at least not yet!

There is one Egyptian company, though, that has already broken free from this mould. It is one of the most vivid examples for Digital Decolonisation ("DigDec"), as described in my last Weekly Dispatch.

Over the coming years, further such companies are likely to emerge in Egypt.

Along the way, vast amounts of wealth will be generated for investors who have the talent for recognising such opportunities early on. This will include a growing number of local investors, which is another important change compared to how things used to be.

What's the company I am talking about, and why should you know it?

It's called Fawry, and it is Egypt's answer to PayPal.

You are unlikely to have heard of it because its stock – at least for now – only trades on the Cairo Stock Exchange.

Nor are you likely aware of the chain reaction of events that Fawry's success has helped trigger for investors in its home country, and which will spread further over the coming years. Massive change is afoot in the most populous country of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, and in similar developing countries around the world.

If you develop a deeper understanding of these developments, you could benefit from what might be one of the most powerful investment trends of the 2020s. It could be as good as travelling back to 2010 and investing in the FAANG-BATS before that trend took off.

Tapping into this trend does require a fair bit of knowledge, though.

Fear not, Undervalued-Shares.com has researched all the details for you. It's quite a story!

A vast, virgin market for electronic payment providers

While Egypt is world-famous for its glorious past, it hasn't exactly been a beacon of economic success and technological innovation as of late.

The country's GDP per capita is just about USD 3,000.

In comparison, even Turkey's 82m people enjoy a GDP per capita of USD 9,000, while neighbouring Israel comes in at USD 43,000.

By most measures, Egypt is a developing country. Almost a third of the population live in poverty, even when measured by the relatively low local standards.

The country has long been lacking a local retail banking market or even basic electronic payment mechanisms. Less than 20% of its 100m population have a bank account. According to the World Bank, Egypt has one of the world's lowest banking service penetration rates.

In Egypt, cash had long remained king. Not only were salaries mostly paid in wads of Egyptian pounds (1 EGP = USD 0.064 or EUR 0.053), but utility bills, traffic fines, car licenses, education bills, subscription services, donations, and insurances also had to be settled in person using cash.

Where someone had succeeded in getting a debit card, these generally had the salary loaded onto them by the employer, which was then withdrawn in cash once a month. In other words, even those Egyptians who did have plastic in their wallet only had a shallow relationship with the card issuer.

The Financial Times described it in a 2012 feature:

"If you are a well-off Egyptian and you need to pay a household bill, you hand over the cash to your driver, office messenger or house porter and send them to queue and pay it on your behalf.

Those not privileged enough to have people they can send on errands – that is, most Egyptians – have to do it themselves every month. To make life easier, utilities send cash collectors to customers (electricity companies dispatch 28m hand-carried bills every month). Often the client is not at home or does not have the amount required at hand. The collector is then supposed to come back another day."

In terms of electronic payments, Egypt until recently was where the rest of the world was pre-1980.

This made Egypt a ground-floor opportunity for anyone who managed to create an electronic alternative.

The potential benefits of switching from cash to electronic were obvious:

- Lower transaction costs.

- Improved convenience.

- Financial inclusion of the unbanked.

The question was, how to make the leap from a cash-based, unbanked society to one using electronic payments?

The hurdles were formidable.

Ten years ago, four out of five Egyptians didn't even have access to the Internet.

Never mind the challenge of convincing potential clients that your electronic payment system would be secure and reliable. Why risk an unknown system when you have successfully kept your cash under the mattress for years or even generations?

One entrepreneur was convinced that he had figured out a pathway to getting the job done.

Introducing Fawry – the PayPal of Egypt

Ashraf Sabry is a former IBM salesman turned entrepreneur.

In 2009, he set up Fawry, the first company to make electronic payments accessible to the entire Egyptian population.

The company is largely unknown outside of the MENA region, but it has become one of the fastest-growing and biggest digital ventures in Egypt and the rest of the region.

Fawry created a national network of payment hubs that connect shops, banks, and websites on a single platform. Instead of trying to change the local payment landscape, Sabry developed software that taps into existing facilities and habits. The payment platform now operated by Fawry is a truly Egyptian solution and one that has grown organically over the past decade. It'd be near impossible for anyone to replicate.

What looks like the proverbial overnight success today initially faced the usual difficulties of any start-up. Despite winning the support of some local institutions early on, winning business proved difficult initially. On more than one occasion, Sabry's venture nearly went bankrupt.

Fast-forward a decade, and Fawry can provide payments through 200,000 service points in over 300 Egyptian cities and towns. These service points range from the headquarters of national banks in downtown Cairo to vendor kiosks in remote parts of the country – and anything in between.

Fawry can handle electronic payments for 894 different services, meaning Egyptians can now run much of their lives based on electronic payments.

A staggering 29m Egyptians have already signed up, and account for 3m transactions made every day.

Fawry has an English-language investor relations website.

Long gone are the days when Sabry had to worry about generating revenue. Fawry has yet to publish its results for 2020, but the most recent quarterly report indicates how well the business has fared during the pandemic.

During the first nine months of 2020, the company generated revenue of USD 57m (up 45.2% compared to the same period of the previous year), and doubled its net profit to USD 7.5m.

Like anywhere else, the pandemic provided Fawry with additional wind under its wings. Also, it's become visible yet again that digital payment platforms tend to grow their profits faster than revenue, once they achieve a critical mass.

In 2019, Fawry processed payments totalling about USD 3bn while for 2020, the figure is likely to be closer to USD 5bn. From a Western perspective, this may seem negligible: in comparison, PayPal processed payments totalling USD 936bn in 2020.

Still, in a country with a total GDP of just USD 300bn, Fawry processed payments equivalent to 1% of the entire national economy.

Also, keep in mind where PayPal once started. During the late 1990s, using PayPal still had a stigma attached to it. There wasn't any assurance that goods would be delivered or that faulty payments would be recovered. It was a wild west situation, and PayPal was widely considered a risky proposition. As it turned out, this was also the time to invest.

When it first went public in 2001, what is today the Western world's best-known online payments company was a USD 1bn minnow (before it was temporarily taken off the market by eBay, only to do a second IPO later). Today, PayPal has a market cap of over USD 300bn. If you manage to have a business compound at 20% to 30% p.a. for two decades, the result can be staggering. Since its second IPO in 2015 alone, PayPal stock is up 20 times.

Did you miss out on buying into PayPal early on? Investors believe they may have spotted a similar early-bird opportunity in Fawry.

The first-ever moonshot tech IPO on the Egyptian stock exchange

Fawry has come a long way since struggling for financial survival.

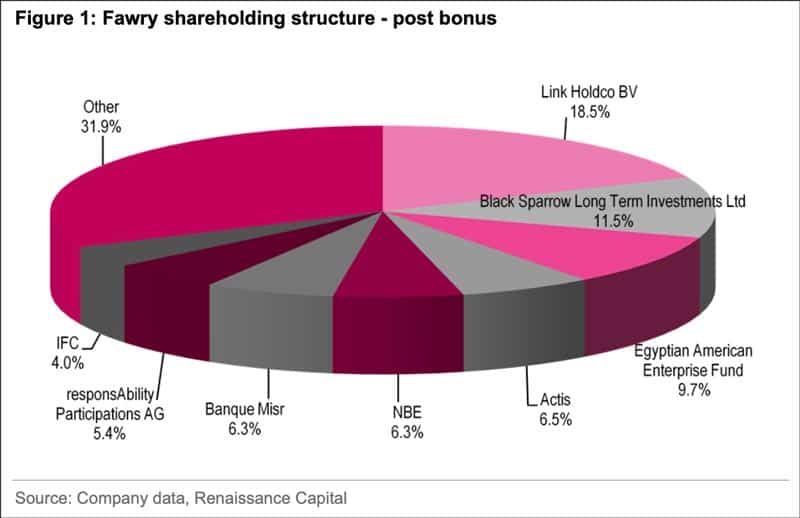

During its early days, Sabry succeeded in signing up investors such as Raya Holding (an Egyptian investment conglomerate), the Arab African International Bank, the Bank of Alexandria, HSBC, and the International Finance Cooperation (the investment arm of the World Bank).

By 2015, Fawry was valued at USD 100m. That year, most of the existing investors sold their shares to a new group of investors.

In August 2019, the owners took the company public at a valuation of USD 275m.

Notably, Fawry didn't list on Nasdaq but decided to keep it local. The company IPOed on the Cairo Stock Exchange. It was the first financial technology company to go public in Cairo.

Egyptian investors and pioneer market specialists loved it. The stock is currently trading at EGP 47 compared to its IPO price of EGP 6.46. That's up seven times in less than two years.

Fawry now has a market cap of USD 2bn, making it one of the most valuable companies listed in Cairo.

It now seems incredible that the stock initially had a lacklustre performance. During the first eight months as a publicly-traded company, the stock went sideways, and it wasn't until the onset of the pandemic that it started an incredible run to its current level.

Based on the expected 2020 results (which are due in late March 2021), the stock is trading at a price/earnings ratio of about 190. That appears expensive in absolute terms, and it is many times higher than the typical valuation of publicly-listed Egyptian companies. Most Egyptian blue-chip companies trade at a price/earnings ratio of 5 to 10.

Still, investors keep piling in, at least for now. They see an opportunity for Fawry to continue its rapid growth for years to come, which would eventually make today's valuation a bargain after all.

Could they be right?

I have researched some facts and figures that provide a better context for anyone who wants to take a closer look. At the very least, Fawry will teach you what to look for if you are keen on investigating similar opportunities.

A nascent market if ever there was one

Egypt is, by any means, at a very early stage of developing its electronic payment market.

The percentage of payments done electronically via a service point recently amounted to just 2% of GDP (about half of that was done through Fawry).

Even India, widely viewed as one of the world's leading examples for an underdeveloped online payment market, already processes the equivalent of 6% of its GDP through electronic payment mechanisms.

Brazil and Turkey are nearly five times more advanced with a penetration rate of electronic payments of 19% and 20%, respectively.

By 2024, the number of electronic payments in Egypt is projected to double when measured as a percentage of GDP. There'll like be some growth to the underlying GDP figure, meaning the market's absolute size will probably more than double between now and then.

Even faster growth is projected for a sub-sector of Fawry's market, mobile wallets. The market penetration of mobile wallets was just 2% in Egypt in 2019, compared to 20% in Pakistan or 33% in Bangladesh. Egypt does have a lot of catching up to do even by pioneer market standards!

In early 2020, Fawry introduced "MyFawry", a "lifestyle super app". The app allows its users not just to make payments through the mobile phone, but also to purchase all sorts of services ranging from deliveries to getting a motorcycle taxi. By the end of 2020, Fawry had achieved 1m downloads on the Google Play Store and a 4.3 (out of 5) rating among users.

Needless to say, the competition isn't asleep.

MyFawry primarily competes with an app offered by Vodafone which already had 10m downloads, but only 1m of them were active users. For Vodafone, the app is an add-on rather than its raison d'être and therefore, the services offered are quite limited in comparison. Three other competitors were last seen trailing behind Fawry with half the number of downloads.

Fawry does need to fend off competitors, but its existing market position, its access to cash to fund improvements of its service, and its focus on electronic payments should ensure that it keeps the upper hand.

Egypt currently has about 95m mobile phones in circulation, 30m of which are smartphones. Citi Research analysts, who have been covering Fawry extensively, estimate that the company could grow MyFawry to 8m active users by 2024.

On a group level, Fawry is currently projected to grow its revenue by an average of 32% p.a. between 2020 and 2024. That'd see the company grow its revenue by a factor of four.

There are no earnings projections available at present that attempt to look all the way to 2024 (not that I am aware of). Citi Research's most recent projections give the stock a price/earnings ratio of about 90 based on expected 2022 earnings.

A bargain? Hardly.

Fawry is currently valued at about 25 times estimated 2020 sales. That makes it more expensive than PagSeguro Digital (ISIN KYG687071012), a comparable Brazilian company that is popular with institutional investors. Compared to the valuation of almost all other peers from around the world, the current stock price of Fawry is quite ambitious.

Will that stop the stock from rising yet further?

In this day and age of narrative-based investing and retail investor stampedes, anything is possible.

Fawry certainly makes for a compelling narrative. Local investors, in particular, love to latch onto a company that they feel has had such a positive impact on their lives.

Fawry stock recently benefitted from its inclusion in the index of the 30 largest publicly-listed Egyptian companies (EGX30). That made for additional demand from funds that try to replicate the index. Also, the stock could yet become a go-to investment for funds seeking to get exposure to growth companies in the MENA region.

Also, it remains to be seen whether existing major shareholders are willing to part from their stock. The long-term story is potentially SO powerful, and the market cap so small compared to other tech companies, that some large shareholders may be tempted to simply sit on it for some more years. Currently, just 32% of the company are in free float, meaning there is only stock worth about USD 700m going around.

An important date to watch is the third quarter of 2021 when the lock-up period of pre-IPO investors ends. If major shareholders started to sell stock, it could add significant pressure to the market. If they don't, it could add further to the "FOMO" (fear of missing out) among other investors.

Could it pay off to tuck away some Fawry stock and not look at it again until 2030?

Quite possibly. (Provided, of course, your broker can purchase stocks in Cairo.)

Egypt, through sheer population size and favourable demographics, has oodles of potential. If the country managed to pursue a similar path as Turkey, Fawry could remain a growth company for years (or decades) to come and multiply in size many times. The company is widely predicted to unveil additional services that could add further to its growth prospects, it might expand to other countries in the region, and it could easily turn itself into an incubator for other fintech ventures in Egypt.

Keep in mind, though, that pioneer markets entail all sorts of risks. To name just the most obvious one, politics is an ever-present danger in Egypt, as seen during the two Egyptian revolutions in 2011 and 2013.

For Western investors, the real attraction of Fawry could lie in a different aspect altogether.

Ground-floor opportunities in nascent markets should be about buying in at lower valuations than at home. All the exciting developments notwithstanding, most emerging markets still lack sufficient access to growth capital. This, in itself, makes for more attractive opportunities.

In many Western countries, too much venture capital funding is fighting over the best deals, which has left valuations inflated like never before. Investors who dare to go further afield can find themselves better deals simply because there is less competition. It's really just common sense to look at opportunities in places where lower valuations and earlier growth cycles give you a better chance of growing your money.

Instead of chasing Fawry, you could be better advised to look ahead and find the next Fawry (or two) before everyone else does.

For more "Fawries" there will be, that's a certainty!

Let me tell you how Fawry is already spawning the next generation of comparable investment opportunities and why it's worth keeping them on your radar.

One success story can create a dozen more

In last week's primer about the DigDec movement, I described how a single successful tech company in an emerging market can transform the local start-up scene. One company can literally change the investment landscape of a country.

Fawry gave equity to its staff, and many local investors bought shares during and after the IPO on the Cairo Stock Exchange. Many early investors who held on to their shares are now sitting on enough money to seed their own start-up. Even someone who sold out earlier may now have enough money to turn into the next generation of tech entrepreneurs.

The following example illustrates as much.

Madga Habib was one of the co-founders of Fawry. She decided to leave the company in 2015 because she was offered a good amount of money for her stake. At the time, a group of investors decided to buy out most of the existing investors based on a valuation of then USD 100m.

Habib has since moved on to launch Dawi, a start-up that she hopes will become the "Starbucks of healthcare in Egypt".

There had long been a gap in the Egyptian healthcare market. The wealthy would generally use expensive private clinics or even travel to other countries for major treatments and check-ups. The vast majority of the population, however, has to rely on the outdated, underfunded public healthcare system.

Surely, there would be room for a reasonably priced service that addressed the country's growing middle class? Given the advances in technology, creating such a service had just become a lot easier. The opportunity was waiting for someone to run with it.

Habib signed up two Egyptian co-founders to create a business model based on standardised clinics with the aim of rolling them out across the country. The clinics would benefit from centrally managed guidelines and standards, a simple yet innovative measure in an underdeveloped country like Egypt. The headquarter would be responsible for training doctors and make them stick to a clearly structured delivery mechanism. A more proactive approach in using affordable technology would provide better care than anything available in the public sector.

Five years later, Dawi has become a success story, operating 12 clinics in three Egyptian cities. Telemedicine has become an integral part of the clinics' offering, and the management is constantly working on using additional emerging technologies to make healthcare more affordable and more effective. Given that it built its entire system from scratch, Dawi wasn't held back by legacy issues that the public sector usually suffers from.

By 2023, Dawi aims to operate 50 clinics across Egypt.

You can read an in-depth feature of Habib's efforts to grow Dawi in this 13 January 2021 feature in How we made it in Africa.

Thanks to the cheque that Habib was able to cash in after her exit from Fawry, another significant local growth company has come into existence.

And Habib is just one of MANY Fawry employees and ex-employees who are now creating their own start-up.

A look at the region's figures makes for some eye-popping realisations. In terms of the percentage growth rates that can be expected over the coming years, Egypt is at the forefront of a powerful new trend.

For tech start-ups, Egypt is where it's at (in the MENA region)

Start-up hubs and outstanding investment opportunities can sometimes be found in unexpected places.

I already demonstrated as much in my three-part series about Poland (see my 17 July 2020 article "Investing in Poland (part 2): Silicon Valley billionaire predicts 'golden age'"). This series initially got a muted reaction from my readers - as always when I write about a subject that is slightly ahead of the curve. Change arrived quickly, though. The recent spate of successful tech IPOs in Poland, coupled with the relative lack of reporting elsewhere, have ensured that these eight-month-old articles keep getting new attention.

Something similar is bound to be the case with my current series.

"Egypt, a start-up hub?"

It'll be a while before the rest of the world recognises what's going on around the Nile and why it's relevant for them.

The figures are already available, though. Anyone who cares to take a look will be surprised what's unfolding right now.

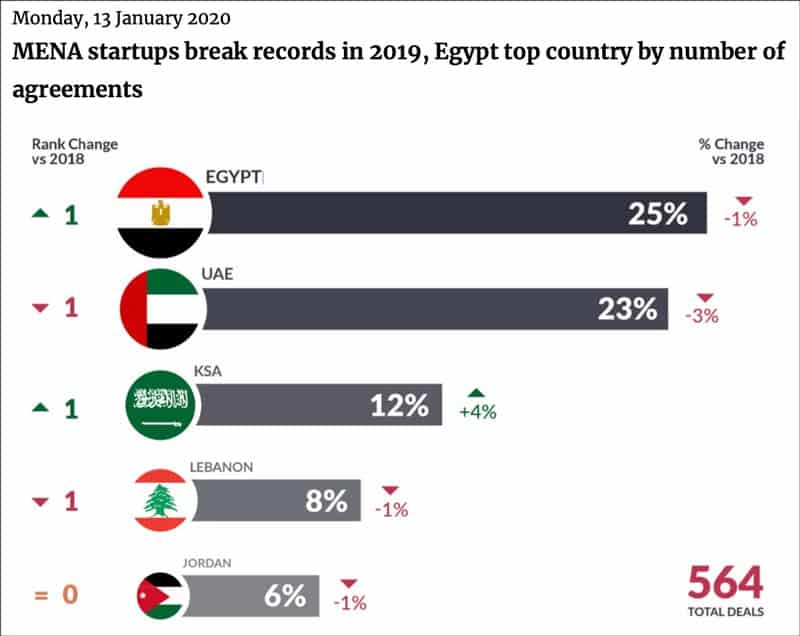

Dubai and other parts of the United Arab Emirates may have a global reputation as glitzy high-tech destinations, but Egypt takes the biscuit for start-up funding and growing new businesses. Yes, Egypt!

In 2019, 25% of the region's venture capital flowed into deals in Egypt, ahead of the UAE claiming 23%. Saudi Arabia (12%), Lebanon (8%) and Jordan (6%) all came in quite a few pegs lower.

Source: Enterprise, 13 January 2020.

Why Egypt?

With its population of 100m and a median age of 24.6 years, the country offers enormous economies of scale to anyone who can create scalable solutions. The UAE, with just 10m people, and even Saudi Arabia, with 33m, can't get close to Egypt's total addressable market.

If you want to make it big by funding start-ups in the MENA region, Egypt is the obvious place to look at. It's also part of the growing domestic ecosystem of venture capital financiers and entrepreneurs.

Another co-founder of Fawry, Mohamed Okasha, stepped down from the company to create his own fintech start-up fund. In April 2020, he announced his aim to raise an initial USD 25m for the vehicle.

A ludicrously small amount? By Western standards, yes.

However, the relatively early stage of the overall market also makes it clear why a single successful start-up can have a transformative effect on the country.

Fawry is now worth USD 2bn. The company will have minted quite a few millionaires, and many employees will have earned thousands or tens of thousands of equity dollars. At the time of the IPO, 8% of the company were owned by employees (including management).

Add to this local retail investors who hopped on the bandwagon after Fawry went public. At times, 80% of the trading volume in Fawry stock was traced back to retail investors.

At least some of these investors will have managed to ride Fawry stock for a good part of the journey, giving them money to reinvest elsewhere. Suddenly, Egypt has gone from having almost no venture capital to having a local scene of active funders. An experienced funder and executive like Okasha could end up catalysing a dozen new fintech companies.

From their very low base, these markets are bound to experience very high percentage growth over the next three, five and ten years.

In 2019, start-ups across the MENA region received funding worth USD 704m. That's about the equivalent of a single medium-sized venture capital deal in Silicon Valley, but spread across a region of 19 countries with a population of 578m people!

These figures illustrate that a single successful IPO by a local company can generate local wealth of such a magnitude that the region's entire venture capital sector gets a notable injection of additional capital.

As a case in point, in 2017, Amazon acquired Souq, an Arabic-language e-commerce company, for USD 580m. A good chunk of that money went to local investors, and parts of it will have found its way back into the local start-up ecosystem.

In 2019, Uber acquired Careem, a competitor based in Dubai, for USD 3.1bn. Again, local investors benefitted significantly, and some of these funds will already be back in circulation.

Given these success stories, it's not difficult to figure out what will come next. The venture capital ecosystem of the MENA region is bound to experience a massive influx of capital over the coming years, and domestic money will play a significant role.

Never mind the fact that foreign investors from further afield are waking up to the opportunity, too. Check out this 2019 feature about Halan, an Egyptian ride-hailing app comparable to Uber. You'll spot a familiar name in the article. David Halpert, the Singapore-based founder of Prince Street Capital Management and inventor of the term "DigDec", introduced the Egyptian firm's founder to his peers at Gojek in Indonesia and provided seed funding for the company. Halpert had already provided seed funding to Gojek, which has subsequently become a deca-corn (a unicorn worth over USD 10bn).

Five years ago, Halan's founder would have been desperate to get a meeting with Silicon Valley gurus. Instead, he went to Indonesia for inspiration and Singapore for seed funding.

This is all part of the growing trend of emerging markets creating domestic tech companies and clever investors making a fortune on the back of it.

Throughout the 2020s, at least some parts of the world will see a shift away from the dominance of American tech companies. Instead, they will experience the growth of an entirely new range of companies that have firm roots in their home countries or regions.

It'll be a good thing, on more levels than one.

"DigDec" as a lens to observe these developments

Fawry is a picture perfect case study of a company that fits the DigDec investment theme that I introduced to you last week.

The company didn't invent anything new. The computers used to build the company were probably all manufactured in China. Its business model isn't unique. Electronic payments have been around for decades.

Yet, Fawry found an opportunity that none of the Amazons, PayPals, Googles, Alibabas, Tencents or TranferWises of this world were able to capitalise on.

Egypt is a unique market, and it took local talent to crack it.

Put another way, technology and capital markets are now at such a stage of development that nothing stands in the way of local entrepreneurs super-charging their projects without much involvement from abroad.

I was reliably informed that if I went into the Fawry head office, I wouldn't find a single foreigner working there. As Mohamed Okasha put it in an August 2020 YouTube interview, "The Fawry software was fully developed by Egyptians in Egypt."

It's a trend that much of the world has yet to realise even exists.

Finding tech companies in poor, underdeveloped countries and seeing them become unicorns and stock market stars isn't what you'd commonly expect to see.

However, you'll probably see a LOT more of it during the 2020s.

Outside of our interest in investing, this has got to be a good thing for the world. Companies such as Fawry reduce poverty through new employment opportunities. They even decrease the pressure to migrate to the Western world. From a policy perspective, these are developments that help stabilise the world.

For a vivid description how Fawry has changed the day-to-day life of Egyptians, check this November 2019 article by the International Finance Corporation. It's a fluff piece written by PR people to talk up the IFC's impact, but it has some good examples of the difference Fawry has made to the lives of millions of Egyptians.

As the example of Fawry demonstrates, a single successful company of this kind has the ability to massively change the prospects of a formerly poor country. Egyptians wouldn't have had much access to venture capital even just five years ago. Suddenly, there is a company worth USD 2bn, and much of this capital can be recycled back into the start-up ecosystem.

Fawry has single-handedly catalysed a virtuous circle for the Egyptian economy.

Undoubtedly, markets such as Egypt will never have the depth and scope as the US or China. Fawry isn't going to turn into a global mega-cap of the FAANG-BATS variety.

However, relative to the existing size of the domestic economy, these companies represent a significant addition.

Last but not least, for private investors, even relatively small companies represent viable opportunities to strike a 10, 50 or 100-bagger. Private investors do not need millions of dollars of daily trading liquidity to buy into a stock, which means they can pursue investments that most investment funds wouldn't be able to get into. Provided, of course, they know where to look.

Tech companies in emerging markets and the entire DigDec theme will make for plenty of opportunities to multiply your money this decade. There is no need to pin all your hopes on the stocks of Amazon, Facebook and Google to rise yet further from their current (ridiculous) level.

SO many opportunities ahead!

You – dear reader – are living at exactly the right time to be there when it's all happening. There is much to look forward to.

2020 will probably turn out to have been a difficult but important inflexion point. Globalisation is bound to retreat in many ways, and we are likely to see more localism, protectionism and nationalism. Like it or hate it, but that's the direction the world is heading.

There is an opportunity to be ahead of the crowd, just as you would have been had you piled into the FAANG-BATS a decade ago.

Using the DigDec lens, you should be able to find future tech champions in developing markets before other investors do. This approach has already produced stunning results in the recent past – as demonstrated by Fawry's IPO – but we are probably still at the very beginning of a trend that is likely to last until 2030 at the very least. Few things are as powerful as companies that manage to keep compounding their growth at rates of 20% to 30% p.a. over a decade.

How best to exploit these developments for yourself (even if you cannot trade stocks in exotic markets)?

What are the unexpected twists and turns you may see along the way when you experience the inevitable traps and troughs?

Which countries should you pay particularly close attention to over the coming years?

These are some of the questions I'll try to provide some answers to next week.

Stay tuned for part 3 of my exclusive series on Digital Decolonisation, the theme that I believe has the potential to become a rock star investment topic in the 2020s.

Blog series: Digital Decolonisation

There's more to "Digital Decolonisation" than this Weekly Dispatch. Check out my other articles of this three-part blog series.

Did you find this article useful and enjoyable? If you want to read my next articles right when they come out, please sign up to my email list.

Share this post:

Save the date: 10 March 2021

I’m eagerly awaiting next Wednesday, when “Europe’s best investment secret” is going to present its Annual Report 2020.

Clients of the company in question have already received a sneak preview of its recent performance:

2020 volume growth:

- Core business: +59%

- Growth division #1: +875%

- Growth division #2: +65%

- Growth division #3: +112%

The stock hasn't moved much since I first featured it in my July 2020 report, but my gut feeling tells me this is going to change very soon. 10 March 2021 is only the start – the entire remainder of the year should yield great results for shareholders.

I urge you to get my report out again if you haven’t already. There’s still time to get in on this opportunity - if only a couple of days!

Get my best investment ideas each year

Join my global audience (Members from over 80 countries!) for hard-hitting investment research that you won’t find anywhere else.

Unlimited access to in-depth investment reports and regular updates - for just USD 49/year, or USD 999/lifetime.

FIRST TIME HERE?

LET'S WORK TOGETHER

Copyright 2021 - Undervalued Shares. All rights reserved. | Privacy Policy | Cookies | Terms & Conditions